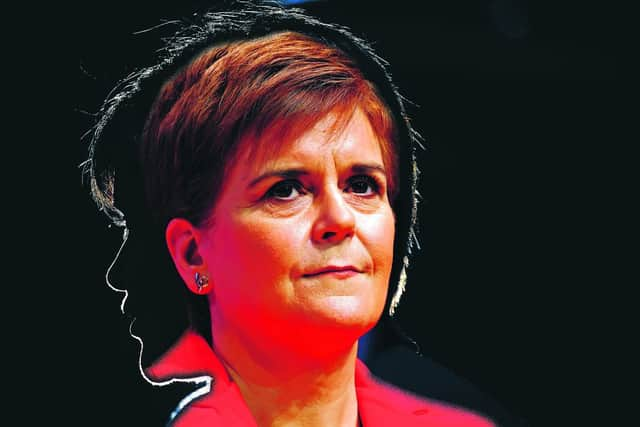

Nicola Sturgeon resignation: First Minister's downfall and the week that shook Scottish politics

Political anoraks would have recognised a reference that stretched back more than three centuries, first uttered by the Earl of Seafield as he signed away Scotland’s sovereign independence. Ms Sturgeon, a glint in her eye, told MSPs that under her watch, that lament would be adorned with new verses, ones that tell the story of a “modern and confident Scotland, fit for purpose, and fit for all her people”.

Eight years and three months later, does the song remain the same? The union, though bruised and battered, remains in place, and Ms Sturgeon has just weeks left in the top job. Having kicked off her premiership with a popstar-style nationwide tour, where venues sold Sturgeon-branded merchandise and chimed out crowd-pleasing ‘80s rock anthems, the beginning of its end was marked by a sombre press conference in the buttoned-up splendour of Bute House.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy choosing the moment of her sudden departure, Sturgeon tried to define her own legacy, and frame her departure as one final service carried out on behalf of her party and country. But after one of the most momentous weeks in modern Scottish history, there are hard truths to be reckoned with. Her party has no obvious successor and no unified strategy by which to pursue its foundational goal of independence. Her country, its public services creaking, remains starkly divided along constitutional faultlines.

History may well recognise Sturgeon as one of the most formidable politicians of Scotland’s devolutionary era, and even without the benefit of hindsight, that status seems in little doubt. Yet mounting questions over her judgement have led many to question whether her resignation is not, as she presented it, an act of duty, but a downfall expedited in recent weeks and months by her own failings and missteps.

The future facing the SNP and the country at large is fraught with uncertainty. A party in power for 15 years now faces a potentially fractious leadership contest, its first in nearly two decades, and doubt surrounds key policies that have not only exposed divisions among nationalists, but across the nation. Whoever succeeds Ms Sturgeon to become the sixth first minister of Scotland is guaranteed a troublesome inheritance.

The issue of independence, unsurprisingly, will be front and centre of their concerns, even with the special conference to determine the party’s strategy on the issue having been postponed while a new leader is selected. The gathering, originally scheduled to take place at the Edinburgh International Conference centre on March 19, had been viewed as a seminal moment for the SNP.

Sturgeon said one of the reasons she was announcing her resignation now was to “free” the party to “choose the path it believes to be the right one” at the conference, reasoning that whatever view she would have expressed would have been decisive. “I can’t in good conscience ask the party to choose an option based on my judgement whilst not being convinced that I would be there as leader to see it through,” she explained.

That view, to be clear, was deeply contentious. Having lost her gamble in the Supreme Court, Sturgeon surprised many by deciding the next general election would be fought by the SNP as a de-facto referendum. It was a strategy fiercely opposed by many in her party, and one senior SNP figure also expressed misgivings at her failure to address concerns over independence that date back to the 2014 referendum.

“The Building a New Scotland policy papers were welcome, but they were overdue, and let’s be honest, they didn’t have the detail or timescales people want,” they explained. “There’s a need to change the way we convince people about independence, and clarity around issues like EU membership and currency are going to be essential.”

Even if the conference ultimately goes ahead, it requires a certain degree of guile to suppose that it will somehow conclude with the party having united behind a common goal. The SNP remains a patchwork of gradualists and fundamentalists, and the consensus of recent years has been won by Sturgeon’s force of personality. If anything, those divisions could open up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSeveral senior SNP members, including Westminster leader Stephen Flynn, Glasgow South MP Stewart McDonald, and Toni Giugliano, its policy convener, had identified clear pitfalls, and had called for the conference to be postponed before that decision was confirmed by the SNP’s national executive committee on Thursday night.

Whatever tactics the next first minister deems the best fit to achieve independence, they will also have to reckon with shifting tides in UK politics. The next general election is less than two years away, and Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer, eyeing up electoral opportunities in Scotland, has become an even more vocal critic of the Westminster system than some SNP backbenchers. If he becomes prime minister, he has promised a major expansion of devolution. Having become accustomed to the Punch and Judy politics of constant sparring with the Tories, that eventuality would force senior figures in the SNP to carefully consider their next step.

Sturgeon’s resignation also leaves her successor with the conundrum of trying to unite the party, and indeed, the country, over gender issues. During her resignation address, Sturgeon said one of the reflections that led to her decision was the way in which public perceptions of her were being weaponised and used as “barriers” to reasoned debate. “Statements and decisions that should not be controversial at all quickly become so,” she said. “Issues that are controversial end up almost irrationally so.”

She never mentioned it specifically, but the subtext – namely her Government’s gender recognition reforms, and in particular, the controversies around transgender prisoners – was barely hidden. Though she insisted such issues were not the “final straw,” the issue cost Sturgeon political capital, and the next first minister will have to weigh up whether to pursue it with quite the same zeal.

While some possible contenders are staunch in their support of the reforms, and would be expected to continue the legal battle against the section 35 order imposed by Alister Jack, the Scottish secretary, others may seek to amend the legislation, or abandon it altogether. The latter scenario should not be discounted given some senior figures in the party have shown considerably less passion for transgender rights than their colleagues. Indeed, one of the frontrunners for the job, Kate Forbes, was among the signatories to a letter in 2019 which called on the Government not to “rush” into legislation they claimed could change the definition of what it meant to be male and female.

The finance secretary, an evangelical Christian, is a member of the Free Church of Scotland, which follows a strict interpretation of the Bible and is opposed to gay marriage. Forbes has previously admitted to being "guilty" of "tiptoeing around" her Christian faith. If she becomes the next first minister, there may be casualties in the clash of her public and private lives.

There is also speculation Ash Regan, the former community safety minister who resigned from Sturgeon’s Government last year in protest over the gender reform bill, may throw her hat into the ring for the leadership contest. However, she is seen as an outsider, with no significant base of support within the party. Whoever the next leader is, they will not have much time to settle on their stance. Jack’s section 35 order was laid down on January 16, and Scottish ministers only have until the middle of April to contest it.

Some might argue the new first minister must focus on more urgent areas, and demonstrate their commitment to rebuilding Scotland’s beleaguered public services. If so, there will be few areas as important as the NHS. There is no hiding from the fact Sturgeon, a former health secretary, as well as a soon to be former first minister, will leave office with the nation’s health service mired in the worst crisis in its history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn institution still reeling from the pressures of the pandemic and another winter season is beset with problems, many of which predate Covid-19. There is, for example, a yawning number of vacancies that have to be filled. The British Medical Association Scotland has said around three in every 20 consultant positions in Scottish hospitals are unfilled, with around 2,000 GPs also needed to fill gaps across surgeries. Then there are around 6,400 nursing and midwifery vacancies to bear in mind.

While A&E waiting times are now at their best rate since May last year, some context is required. Just 70.1 per cent people are being seen within four hours, which remains considerably short of the Government’s target of 95 per cent. There are also ongoing problems around other treatments. During her time in the health brief, Sturgeon set out a target that 90 per cent of patients should start specialist care within 18 weeks of a GP referral, but the latest figure stands at less than 73 per cent.

A key solution, though not one easily achieved at a time of straitened public finances, will be freeing up capacity. That is inextricably linked to the plans for a National Care Service, hailed by Sturgeon’s Government as the most significant public service reform in Scotland since the foundation of the NHS itself. However, opponents of the scheme have called for it to be paused or dropped altogether, warning that costs could spiral, and questioning its exact role.

Significantly, those who have expressed concerns include several SNP MSPs. If the new first minister hopes to avoid the annual firefighting in the NHS during the cold months, and agrees with Sturgeon’s plans for a transformational reform of social care, he or she must settle on a way forward and gain cross-party support.

Elsewhere, the first few months of the new first minister’s tenure will throw up another curveball in the form of Scotland’s deposit return scheme (DRS). Although the controversies surrounding the initiative are far from the gravest crisis to have engulfed Sturgeon’s leadership, they promise to pose an immediate headache for whoever takes her place. Circularity minister Lorna Slater has insisted the scheme will be rolled out as planned in August, despite growing consternation on the part of retailers, producers, and tellingly, a cross-party group of MSPs.

A factor in that decision, of course, is the DRS is the brainchild of the Scottish Greens, and the extent to which the next first minister supports Slater, the Greens co-leader, will not only have ramifications for the mass-scale recycling initiative, but relations between the two parties in government.

Technically, responsibility for the scheme’s delivery rests with private firm, Circularity Scotland Limited. But it would be politically naive of any first minister to try and absolve their new government of responsibility if, as many are predicting, the scheme encounters teething problems, or worse, disrupts trade, raises prices, and reduces choice.

While senior figures in the business community are holding their cards close to their chest while the SNP begins its search for a new leader, there have already been thinly veiled warnings of the pressing need to address concerns around the DRS, as well as other contentious policies, such as restrictions on alcohol advertising.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Liz Cameron, chief executive of the Scottish Chambers of Commerce, has said the organisation hoped to work with Sturgeon's successor on a variety of areas, including “correcting regulatory policies which are not practically working for business”. Leon Thompson, UK Hospitality Scotland’s executive director, said it was essential the new first minister commits to “create an environment that is fit for purpose, practical, and works for businesses”.

For all the uncertainty, some facts are settled. Whoever takes Sturgeon’s place will not be embarking on giddy, celebratory tours of the country. There is a huge amount of work to be done. The end of ane auld sang is near. Soon, a new verse will be written.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.