Venice Biennale reviews: Alberta Whittle | Sonia Boyce | Simone Leigh

Alberta Whittle: deep dive (pause) uncoiling memory, Docks Cantieri Cucchini ****

Sonia Boyce: Feeling Her Way, British Pavilion, Giardini ****

Simone Leigh: Sovereignty, USA Pavilion, Giardini ****

Advertisement

Hide AdThis year’s Venice Biennale, delayed by a year due to the pandemic, is one in which women’s voices are central. For the first time in the festival’s 127-year history, more than half (more than 80 per cent, in fact) of the artists in the main curated show are women, and this sensibility seems to ripple out into many of the national presentations.

The awards ceremony at the end of Preview Week saw the Biennale’s two prestigious Golden Lion awards go to black women: Sonia Boyce at the British Pavilion for best show, and Simone Leigh, who is showing at the US Pavilion, for her work in the main exhibition. Both are the first black women to represent their countries in Venice.

Meanwhile, Scotland is mounting its tenth exhibition in Venice as part of the city-wide “collateral” programme, also by a black woman, Scots-Barbadian artist Alberta Whittle. Exhibiting in the same venue as Charlotte Prodger in 2019 – Scotland + Venice’s new long-term home at Docks Cantieri Cucchini – she has transformed the rooms of the former workshop with purple walls, green ornamental gates and yellow bespoke furniture in the shapes of punctuation marks.

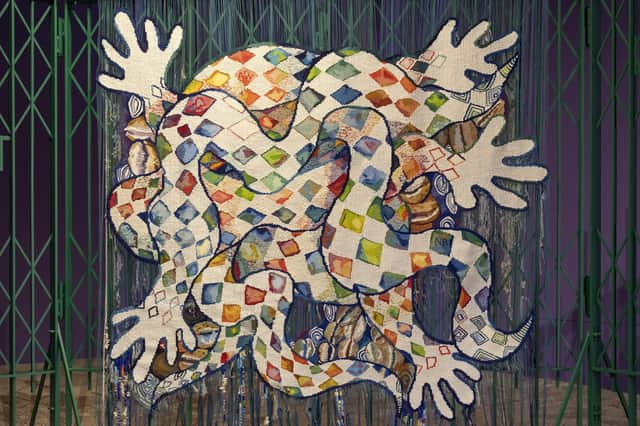

These gates, however, are not barriers; they are more like supports, delicately decorated with eyelets of stained glass or beaded necklaces. One supports a tapestry made to Whittle’s design by the weavers at Dovecot Studios. Entanglement is more than blood is a tangle of limbs, also decorated with beads and braids, and this show is a thoughtful tangling of histories, places and ideas.

Everything here has been placed with care, including a tender painting of Whittle as a child done by her mother, shaping the environment in which we will watch her 40-minute film, Lagareh – The Last Born. It’s an ambitious exploration of anti-blackness, from the slave trade through to the deaths of black men and women at the hands of police in the UK, and runs a gamut of emotions: grief, anger, remembrance, affirmation, healing and hope.

The show needs to be seen in its entirity, a challenge in preview week when everyone is practising a smash-and-grab approach to art-viewing, but it will come into its own in the slower months to come. The invitation to “pause” (perhaps sitting on a comma or a bracket) is timely: you need to slow down to take this in.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhittle’s approach to film-making is collage-based, though here she collages places and ideas rather than found footage. Lagareh begins with a powerful image of black dancer Solariss Kantaris entwined with a snake. It travels to Sierra Leone, to the mass graves of people taken as slaves who died of trauma before leaving Africa, to colonial sites in Barbados where Whittle’s cast of powerful black women wear red and brandish machetes, and to an intimate domestic setting where couple Ama and Ange talk to Whittle about the kind of home they hope to give their children.

It takes in Oswald’s Temple in Ayrshire, once owned by a Scottish slave trader, and pauses in silence on the face of Sheku Bayoh, the young black man who died after being restrained by police in Kirkcaldy in 2015. It ends with a litany of names of those alleged to have died at the hands of the state in the UK and a powerful Mandinkan “praise song” for Bayoh sung by Kumba Kuyateh in a London court room.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe strong soundtrack by Matthew Arthur Williams and Richy Carey helps signal the many changes in mood, from defiant exhortation – “Withdraw your consent to police power” – to intimacy and tenderness. Imagery of water links the various locations, a potent symbol in Whittle’s work of memory, loss and rebirth. Though there is a lot of death in the film, the children in it – Eseosa, playing at Oswald’s Temple, Bayoh’s two children, the hoped-for child of Ama and Ange – act as heralds of new beginnings.

Whittle’s meticulous care over how her work will land with viewers means she is in danger of spelling things out a little too much. The film is strong enough to tell us without the voiceover that every lost life was once someone’s child. The mystical overtones – whispering ancestors, symbolic winds – might feel too whimsical for some when laid next to the cold, hard facts of anti-blackness. However, Lagareh is a significant achievement, not only taking her work to a new level but creating a powerful addition to the cacophony of voices at the Biennale.

While Whittle’s practice is collaborative, supporting the work of her “accomplices” many of them black artists themselves, Sonia Boyce goes still further, using her work for the British Pavilion to foreground others. The piece is a continuation of her “Devotional” project which celebrates the centrality of black British female musicians in the cultural sphere – though the fact that such a celebration is necessary signals that many of these women have been overlooked.

For her Venice commission, she invited five contemporary musicians, singers Jacqui Dankworth, Poppy Ajudha, Sofia Jernberg and Tanita Tikaram, and composer Errollyn Wallen, to London’s Abbey Road studios to improvise, experiment and generally unleash their creativity. After the stillness and delicacy of Cathy Wilkes’ exhibition at the British pavilion in 2019, the rooms pulse with noise, video screens, metallic furniture and bright tessellated wallpaper.

Voices entwine in harmony and counterpoint in the central space as the women respond to one another, throw inhibition to the winds and growl like animals or chime like bells. Then, in individual rooms, they showcase something of their own styles, while the sound bleeds pleasantly from one room to the next. It’s raw, unpolished, unresolved, but it has the energy of creativity actually happening before our eyes in a way I haven’t seen anywhere else in Venice.

This contrasts dramatically with the poised, polished sculpture of Simone Leigh at the US Pavilion. Her work begins with the building itself, adding a grass roof to reference the kitsch pavilions at the Paris Colonial Exhibition of 1931, now widely recognised as racist, and a towering female sculpture, part tribal art, part satellite dish, beaming out her message.

Advertisement

Hide AdHer work creates images of black women on a monumental scale, responding to the ways in which such images have been used in the past. The first sculpture in the show, Last Garment, a woman stooping to do laundry in a stream, is taken from a 19th-century photograph of a kind used to promote Jamaica to white tourists, an exotic paradise with “loyal, disciplined and clean” inhabitants.

She challenges these images by celebrating the women in them, making them strong and monumental: the towering Sentinel at the centre of the pavilion, the female sphinx, the twice-life-size portrait of black writer Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts. Her work shines, too, in the main Biennale exhibition, Cecilia Alemani’s The Milk of Dreams, with her 16-feet tall sculpture Brick House, part bust, part building, towering over the first room at the Arsenale.

Advertisement

Hide AdConceptually, these works subvert and challenge existing images and outmoded assumptions, but they also function on a more straightforward level. By their craft and their scale, they are monuments to the overlooked history of black women, to their strength, resilience and vision. She puts them in charge of themselves, gives them sovereignty, and reminds us that no one should dare to dismiss them.

The Venice Biennale runs until November 27, for more information www.scotlandandvenice.com or www.labiennale.org