What links Scotland and Nagorno-Karabakh, amid Azerbaijan and Armenia conflict? A Holyrood restaurant and an independence movement

If you lived in Edinburgh between the 1980s and early 2000s, your knowledge of the breakaway former Soviet region of Nagorno-Karabakh was probably predominantly linked to a tiny restaurant in Holyrood.

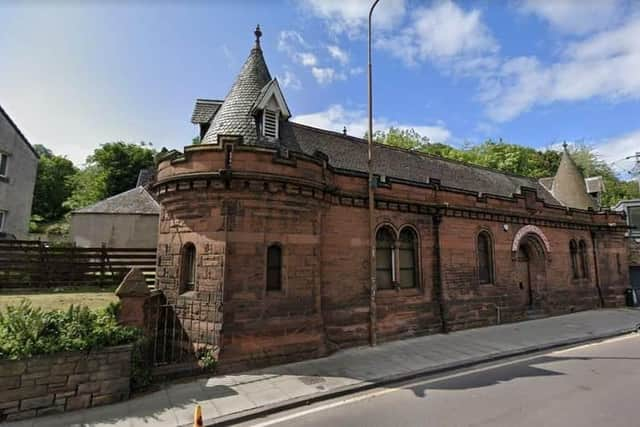

The bizarrely-named Aghtamar Lake Van Monastery in Exile restaurant was known for its good food, Armenian dancing and its eccentric Karabakh owner, known only as Peter. Peter, who only occasionally took bookings through the restaurant’s phone number, which was a closely guarded secret, also reportedly owned a curiosity shop on Edinburgh’s Dundas Street called Gallery Nagorno-Karabakh. That shop was rarely open – and now lies derelict and overgrown with weeds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe whereabouts of Peter, who two years ago sparked rumours surrounding the potential reopening of his restaurant after a new sign mysteriously appeared above the door, is unknown. He never did reopen it. Maybe he is still in Scotland, or perhaps he has gone back to his homeland, which was this week attacked by the Azerbaijan military for two consecutive days.

The assault sparked fears of a resurgence of the “Second Nagorno-Karabakh War” in 2020, which lasted for 44 days and killed thousands of people. The ceasefire has since been unstable and hundreds of troops have since been killed in border clashes.

Baku said it was carrying out the attacks under an "anti-terror operation". An agreement by the Karabakh military to disarm came quickly and, on Thursday, talks were held to discuss integrating the region fully into Azerbaijan. It has always been internationally recognised by Azerbaijan, but has been controlled by ethnic Armenians. Peace talks held in the US earlier this year failed to resolve the issue.

However, in Armenia, protesters rallied outside the Parliament, demanding the Government take action to protect ethnic Armenians in the breakaway state.

Peter is not the only link between Nagorno Karabakh and Scotland – both are small countries with an interest in independence. Back in 2014, the ethnic Armenian leadership of Nagorno Karabakh welcomed Scotland’s independence referendum, as did many residents of the breakaway region.

One ethnic Armenian man told a local newspaper at the time that Scotland’s independence would set another “important precedent” for Karabakh. “We could use it for Karabakh’s international recognition,” he said. That man will, of course, have been sorely disappointed.

It is not likely to have had much to do with the Scottish indyref, but the likelihood of Karabakh becoming an autonomous region now seems low. Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev hailed the ceasefire as a “major victory” and said he was committed to a “peaceful integration”.

Not everyone is as upbeat.

International observers have not been able to reach the region for months, since Azerbaijani blockades of a key land corridor between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia were put in place. Karabakh Armenians have raised fears of ethnic cleansing and have said many of their community may be forced to flee their homes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdReports have claimed the ceasefire has already been broken, something Azerbaijan has vehemently denied. When I met the Azerbaijani ambassador Elin Suleymanov in Edinburgh earlier this year, he told me his government believed peace in Nagorno-Karabakh was “fundamental” in a region destabilised by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“I hope my Armenian neighbours understand that,” he said.

Something tells me it won’t be that simple.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.