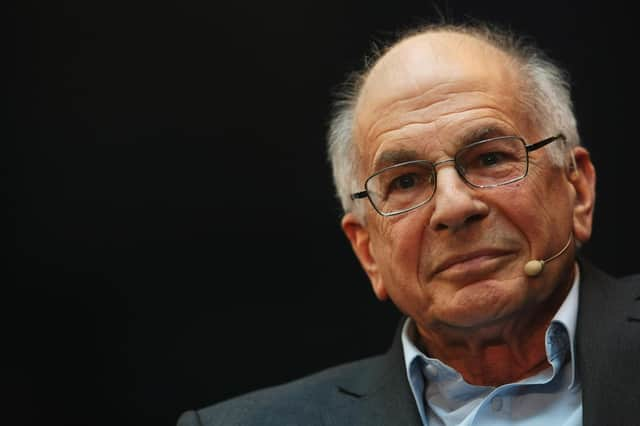

Scotsman Obituaries: Daniel Kahneman, psychologist and expert in behavioural economics

Although not an economist by training, Daniel Kahneman, as the father of the study of behavioural economics, was arguably the most influential figure in the development of economic thinking over the past 50 years.

His 2012 book Thinking, Fast and Slow has sold more than ten million copies worldwide and still remains in the top 100 bestselling books listed on Amazon, a remarkable achievement for a serious work on psychology and economics more than a decade after its first publication, and a tribute to its clarity, humour and insights into how the human mind works.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBefore Kahneman, economics was based on the premise that human beings are rational, at least when it comes to the decisions we make on how to spend and invest our money.

After Kahneman, it was recognised that this is not the case and there are systematic biases in the way we come to our decisions.

Daniel Kahneman was born in Tel Aviv in 1934, and in 1940 his father was working in Paris when the Nazis occupied it.

The family was on the run for the rest of the war and survived, although Kahneman's father died from diabetes in 1944.

After the war, the Kahnemans settled in the new state of Israel, where Kahneman received his Bachelor of Science degree in psychology and mathematics from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1954. In 1958 he left Israel for the United States to study for a PhD in Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Kahneman settled permanently in North America from the late 1960s onwards, teaching at the University of British Columbia between 1978 and 1986 and the University of California, Berkeley, between 1986 and 1994, before joining the Princeton University faculty in 1993 as Professor of Psychology.

He also taught at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton. He transferred to Emeritus Professor status in 2007 following his retirement from day-to-day teaching at the age of 73.

In 2013, Kahneman was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America's highest civilian award, which was presented to him personally by President Barack Obama at the White House in November 2013. President Obama also included Thinking, Fast and Slow as one of his personal recommendations for summer reading.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was in North America that Daniel Kahneman forged the most important professional relationship of his life, with fellow psychologist Amos Tversky.

Tversky died in 1996; had he lived he would almost certainly have shared the 2002 Nobel Prize for Economics with Kahneman, who generously and unreservedly acknowledged the contribution he made to what the two men termed Prospect Theory.

The central tenet of Prospect Theory is that the decisions we make are framed by whether we see them as potentially enhancing our prospects, in which case we are likely to go ahead, or harming our prospects, in which case we are more likely to decide not to proceed.

As Kahneman observed, “An investment that is said to have an 80 per cent chance of success sounds far more attractive than one with a 20 per cent chance of failure. The mind can't easily recognise they are one and the same.”

In deciding how to frame our prospects, Kahneman found, we have two modes of thought.

Thinking Fast he called System One, when we have to take a decision quickly with imperfect information. Thinking Slow he called System Two, when we have more time to undertake detailed analysis and research, as, for example, before deciding what house or car to buy.

When we have to think fast, we do not have the time or resources to undertake a detailed and thorough analysis of our options, so instead Kahneman found that we use “heuristics” or rules of thumb to arrive at a decision.

So, for example, someone who decides to keep their savings in cash rather than invest in shares might use a heuristic such as “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”, while someone who opts instead to buy shares may say to themselves, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn other words, what decision we arrive at depends on what rule of thumb we're using.

Prospect Theory has been widely applied to medical decisions, such as whether or not to have an operation, and to investment decisions. It could equally well be extended to political decisions and the analysis of history.

For example, in last year's Annual Culloden Lecture, Kahneman, Tversky and Prince Charlie: Cognitive Biases that led to Culloden, which can be viewed on YouTube, I sought to apply Prospect Theory to analyse seven key decisions taken by the Jacobite leadership during the Rising of 1745.

Daniel Kahneman's ideas have applications in areas far beyond those he envisaged, and his legacy will long outlive him.

Obituaries

If you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), contact [email protected]