Life and death with the last of Glasgow’s rivermen

THIS is a story of blood and water. Blood inherited and spilled. Water loved and feared. It is the story of a man called George Parsonage, a city called Glasgow, and the river which passes – like a soul, like a scythe – through the lives of both.

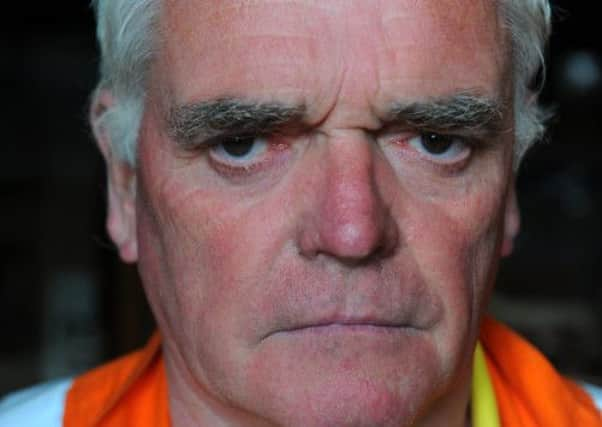

George Parsonage is the chief officer of the Glasgow Humane Society, an organisation that since 1790 has been dedicated to saving the lives of those who fall, either by accident or with grim intent, into waterways in and around the city. He is stocky, strong, quick in his movements. He favours orange boiler suits and stout work boots, softening the leather of each new pair by immersing them – baptising them – in the Clyde. He has a rolling way of walking, as if dry land is a dubious surface. He has white hair and brown eyes; his large hands are rough with years of work, burned by rope and ice, scarred by the jutting, cutting bones of a body recovered from Govan wharf. On Tuesday, he will turn 70. He was involved in his first rescue in 1958, assisting his father who did this job before him, and has saved about 1,500 people since then, his most recent last month.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere will be thousands of children alive now who owe their existence to the fact that a member of the Parsonage family, long ago, was deft and determined enough to pluck their grandparent or great-grandparent from the merciless Clyde, deferring death for a while.

“Rescue is a privilege, isn’t it?” Parsonage says. “It’s not everybody in this world who gets the chance to help someone.”

He lives with his wife Stephanie and two teenage sons on Glasgow Green, in a house on the northern bank, just up from the beautiful blue and gold suspension bridge and his own boatyard. He was born here on October 15, 1943, six years after the house was built. He was one of four children – two sisters and an elder brother. His father Benjamin, known as Bennie, was chief officer from 1932 until his death in 1979, although he made his first rescue as a teenager in 1919. To call this a family business does not go far enough; it was more like being raised in a faith. The words GLASGOW HUMANE SOCIETY are carved in ecclesiastical-looking block capitals above the lintel of his home.

In the study, in the evening, Parsonage writes up the minutes of each day’s work. He has minutes going back to the 18th century, and it is his desire to produce a complete history of the society’s endeavours. It will be, he hopes, a message to the future about safety on the river, a way of continuing his work when he is gone. He wants to open a museum by the house. The history of the Humane Society is, he feels, a social history of Glasgow; it reveals things about the life and mood of the city, its pastimes and its pain: people attempt to kill themselves in greater numbers during times of war and economic depression; in high spirits, through booze or simple bravado, they attempt to go swimming and die.

Reading through the accounts of drownings and the recoveries of bodies is to glimpse citizens at moments of crisis to which, regardless of the archaic language, any of us could relate; “desponding state of mind” is a common reason given for suicide, while deaths are often caused by being “the worse of liquor”. People throw themselves from bridges and river banks because they are “labouring under mental derangement” or “brain fever” or have been “disappointed” by a “sweetheart”. They drown “while trying to sail a toy boat” (1897), “while attempting to drown a cat near to Polmadie ferry” (1897), or while “slightly unhinged by bad news from abroad” (1892). These people were weavers, carters, lamplighters, sweeps, prostitutes, hawkers, bare-knuckle boxers, and children who would never know the world of work.

There are thousands upon thousands of these stories, these brutal statistics, yet sometimes you come across one that stands out, that has a sort of dreadful poetry in it. In the early spring of 1958, a four-year-old from Maryhill fell into the canal and was lost; another boy, the only witness, went home and told his mother what had happened to his pal. “Jackie,” he said, “has gone away with the swans.”

Such accounts can make the Clyde appear accursed or even actively malevolent. Certainly, it is dangerous – deep, steep-sided and very cold. Yet George Parsonage feels no loathing; indeed, he takes joy in the Clyde, and needs little persuasion to leave his study and take to the water. “I’m away down to the boats,” he shouts up the stairs to Stephanie. “I’ll be out on the river.”

IT IS a mild afternoon in early September 2013, but it could be 1938 or 1963 or 1979, as on the Clyde a man called Parsonage is searching for a body. The police came to the door just before lunchtime and asked Parsonage if he could help look for a young man who had been missing for almost a week. So, here he is, a few miles upriver from the Green, his restless eyes scanning the river and its banks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough rescues are the dramatic, newsworthy aspects of the society’s work, these searches have, over the years, been much more common. Parsonage, like his father before him, is skilled in the use of grappling irons – a heavy four-pronged steel hook lowered to the river bed by two ropes and used to drag for murder weapons, stolen goods and corpses. “It’s actually quite a science,” he says. Parsonage can tell from long experience whether he has touched wood or metal; the feel of flesh, sensed along the rope, is unmistakable. “The body begins to rise with gentleness, an uncanny lightness,” he has written in an unpublished essay on what he calls the ancient art of grappling, “and the rope user has to be very quick and gentle in raising the body to the surface. It is like lifting a balloon. If you stop lifting, the balloon will float off and away, so with a body.”

It is a matter of honour for Parsonage that his grappling irons do not leave marks on the bodies. Indeed, his knowledge of the horrors that being too long in the water can inflict is one reason he has always done his best to recover victims of drowning as quickly as possible. He prefers to spare family members the sights with which he is familiar, even if that means long hours out in the freezing dark.

Yet, in truth, searches and rescues are, these days, just a tiny fraction of his work. In 2005, the then Strathclyde Police took the responsibility for rescue away from the Humane Society and gave it to the fire service; the police themselves now recover bodies. It was a bureaucratic decision that felt like the passing of an age; the end of a certain sort of civic heroism. Parsonage sometimes finds himself in the right place at the right time, and the emergency services still, on occasion, seek his help. But the days of being the go-to guy in each life-or-death situation are over. Without police funding, the Humane Society struggles for money, and Parsonage himself no longer takes a wage. He works, now, out of a sense of vocation and, one suspects, forward momentum; like a great ship decommissioned even as it slides down the slipway.

But he is busy. Make no mistake. The Humane Society receives a grant from Glasgow City Council, and has a key role in promoting safety on the river. This is the focus now – preventing people from falling into the water in the first place, or at least making it easier for them to be saved, through the adequate provision of quayside ladders and the like. Parsonage maintains about 300 lifebelts along the banks of the river, retrieving the 20 or 30 each day that are thrown into the water by eejits and drunks. He was responsible for introducing a GPS system which means the location of people in the water can be identified readily when 999 is dialled. He continues to argue for fencing and bridges to be made more safe, making it harder for people to fall or jump, and has had some notable success. “Glasgow’s way ahead of any other city,” he insists. “Goodness knows how many lives we’ve saved.”

Nevertheless, as someone who has, since childhood, been conditioned to respond to emergencies, he does find the present situation difficult. “Every time I hear sirens, or see blue lights downriver, or see the helicopter hovering over the river, my heart misses a beat and the adrenalin starts running. You wonder, ‘What’s going on?’ It’s very hard to keep out of it. You want to be part of it. There’s the public expectation, too. The public could be told a hundred times that I’m no longer on call, but as long as I’m here they will expect me to answer the call. And in this section of the river, we do answer the call.”

When I visited Parsonage one bright Tuesday morning, he was still buzzing from having carried out a rescue on the Sunday night; a boat had crashed into the gates of the tidal weir, near the Parsonage home, and its occupant had been thrown into the water. On some level, he needs this. It’s not that he’s a thrill-seeker, though; he is, rather, a man who takes pleasure in performing the function at which he excels, and which he regards as a vocation.

“God gave me the ability to be a good rower,” he says. “I used to win an awful lot of races. But I didn’t realise until later on in life that the greatest races I was winning was when I was rowing to get someone out the water. That ability, that boatmanship, is there for a purpose. Maybe I’m reading things into it that aren’t there. But it’s nice to think that way.”

Retirement, therefore, is not an option. “There’s a future for the society, and I’m here fighting for it. As long as I’ve got enough strength to keep going.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEACH squeak of the rowlocks, each creak and splash of the oars takes us a little further upstream, a little further into the past. Parsonage is rowing, the memories flowing. “Oh, wonderful river. So much has happened in it.” He nods over to the northern bank. “I found a woman there. She was face down and her shoes were sticking out. We had to get picks and shovels to dig her free. Terrible that I know every inch of the river, and an accident in every inch. I’ve been here too long, eh? Too long.”

Bennie Parsonage loved the river, and – fanciful as this sounds – it seemed to love him. On the day of his funeral, the rain was so heavy the grave flooded and he was lowered into water; the following day, the gates of the tidal weir jammed open and the Clyde dropped until, as Parsonage recalls, “it was hardly a stream in the middle”, as if it did not want to continue without the man who had for so long stood sentinel over it.

Parsonage had been working as an art teacher while devoting his evenings and weekends to assisting his father, but on the day of the old man’s death – October 1, 1979 – he did not hesitate to take over the role. “The love of the river was greater than anything else.” He made a search for a missing woman that very afternoon. Was it, though, a burden he took up entirely willingly? “Don’t know. I had no choice. We had nothing. My mother was in a wheelchair, my sister was at home looking after my mother. There was no house to go to if I had chucked the job. And that very afternoon, when the phone went and somebody needed help, I just did it. That was it. Sucked straight in. I don’t think my father ever wanted me to be here. But I don’t know. I can’t say that.”

It wasn’t a job, it was a calling, and you gave yourself to it. There was no possibility of going on holiday, or out for a meal, or even to put on a pot of soup. You had to be available to run for the boat. Parsonage is glad his sons cannot and will not inherit that life, although he was proud to have his eldest at his side during the recent rescue at the tidal weir. Bennie Parsonage was more than a father to George, he was a hero. He was a wee man, five foot one, and he came from Bridgeton. He had a deep religious faith but was only in church once in his life, and that at his own funeral. He was modest and taciturn. Once, asked by a young newspaper reporter whether people often drowned in the Clyde, he gave a five-word reply that was a masterclass in dry wit: “Naw, son. Just the once.” His son, by contrast, is able and willing to tell the story of the Humane Society, to carry that cargo of memory and love.

We pass under bridges. St Andrew’s, King’s, Polmadie, Dalmarnock. The banks are overgrown and choked. There are apples and pears, rasps and brambles; giant hogweed lends a sinister fairyland air. Parsonage photographs trees falling into the water; he’ll see these are cleared. He points out the piles of an old wooden bridge, poking like rotten teeth just above the surface. He knows what hazards lie in the Clyde’s murk – the deep holes, the sandbanks, the dumped combine harvester that has lacerated canoes. Everything suggests a story. Here’s a length of pipe at the spot where, in 1971, he dived 20 feet below the water to rescue a mother and her five-year-old son. Here’s the bridge where neds almost killed him by dropping a concrete block on his head. Parsonage loves opera, Puccini is his favourite, and it is tempting to imagine a soundtrack playing as he rows, perhaps the aria O Mio Babbino Caro, Oh my beloved father. It would, if nothing else, take one’s mind off the sewage works stink.

In his boatyard, we talk over tea. Outside, his colony of rescue geese chatter and rasp. These birds are music lovers and have enjoyed many bands performing on Glasgow Green over the years; the only act they found unbearable was Marilyn Manson, preferring to head upriver to Rutherglen for the duration of his performance. George laughs as he tells this story, playing the entertaining host, but there’s a part of him that isn’t in the room at all. He has positioned his chair so he can keep an eye on the river, making sure that if any of the rowers overturns he will be able to act swiftly. He is an amiable man full of anecdotes, but that brain is forever calculating worst-case scenarios and plans of action.

I ask about his attitude to the river. Can he define how he feels about the Clyde? “It’s a love/hate relationship. The river can be a wonderful friend, but a cruel, cruel master. You’re fighting against it, and thinking all the time of what it can do to you. You’ve got to give it the greatest respect.”

In some ways, Parsonage is the last of the true rivermen. Read through the Humane Society records and you’re struck by how many vessels and people were on the river at one time. No longer. It is a tradition in the Parsonage family to see in the new year on the Clyde. Parsonage and his father would drift downriver in one of their boats and listen to the bells in the Trongate steeple; then, on the stroke of midnight, Bennie would sound his klaxon. It is something Parsonage continues, at Hogmanay, with his eldest son, Ben – blood on the water, thinking of the past, looking to the future. “Once, all the ships on the river would reply,” he says. “But now, sometimes, there isn’t a single answer coming back.”

Twitter: @PeterAlanRoss

• Volunteers and donations welcome (glasgowhumanesociety.com)