Glasgow Women's Library celebrates 25 years of inspiration

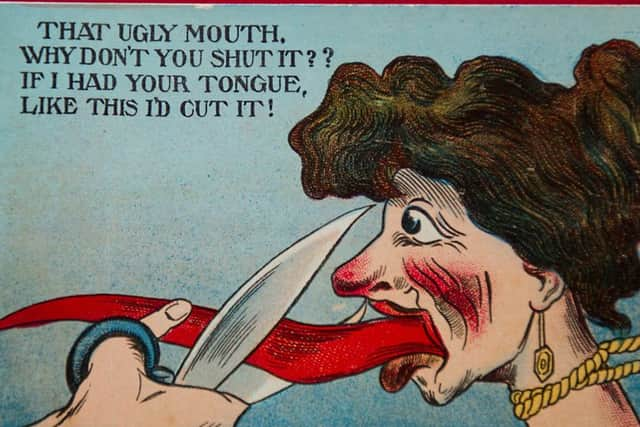

Housed in the Grade II listed Carnegie Library building on Landressy Street, the GWL is jam-packed with quirky artefacts, each of them with a story to tell about women’s history. Many are focused on the feminist movement and the backlash it provoked: there’s the set of postcards depicting women with their tongues nailed to tables, the clock with the picture of a miserable man holding two screaming babies, and a copious number of Spare Rib copies. But there are also souvenirs of “ordinary” lives: a Scottish Women’s Rural Institute cookery book, knitting patterns from the 1930s and Jackie annuals.

The GWL is, as its name suggests, first and foremost a library, and its shelves are crammed with books by female authors, but it is also so much more: a museum, a cultural hub, an educational resource and an agent of social change. Here, minds are expanded, individuals empowered and lives transformed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTake Mary-Alice McLellan from Bridgeton, who volunteers twice a week. McLellan has learning difficulties and was suffering from anxiety when she first ventured in for a showing of The Steamie in 2013. Since then, she has had help with her reading and writing, gone on trips to museums and arts galleries, and spoken out in public; as a result her confidence has soared.

When the GWL staged its March of Women (a procession in which those involved dressed up as prominent figures) McLellan took on the role of former Labour MP, Agnes Hardie, and said her lines with aplomb. “The Glasgow Women’s Library makes me really happy. When I’m feeling down, they boost me up,” she says. It’s made her more independent too. “I went to Kelvingrove Art Gallery myself – I would never have done that before.” Now she is helping catalogue the GWL’s collection of roller derby programmes and memorabilia.

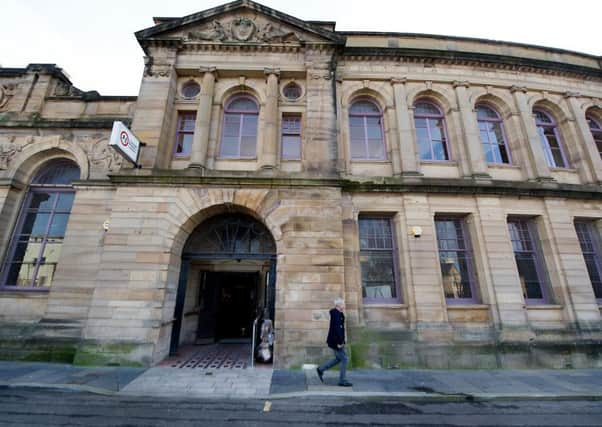

As it prepares to celebrate its 25th anniversary later this year, the GWL is on a high. Two years after moving to its new home, its £1.4 million renovation is complete. Two purpose-built stores have been created, a lift, with an external façade featuring titles from the collection, has been installed, and the men’s reading room has been converted into a flexible exhibition space with a mezzanine. The refurbished building was launched by Nicola Sturgeon in November. Just weeks later, the GWL gained “recognised collection of national significance status”, and last month its founder, the irrepressible Adele Patrick, won Scotswoman of the Year for her hard work in transforming it from a tiny grassroots venture to the facility it has become today.

In the past few years, the GWL has been behind a mind-boggling array of projects such as: Mixing The Colours, which documented the way sectarianism impacts on the lives of women, Revolution 21, in which writers and artists were commissioned to produce works inspired by the artefacts, and Sex Between The Covers: reading writing and discussions about sex. Current events include a Palestinian embroidery workshop and Herland, an irregular evening generally focused on food and music. The GWL also houses the UK’s only lesbian archive; it includes pulp fiction novels from the 1950s which, while written for men and negative in tone, were once the only stories of same-sex encounters lesbians could easily access.

On the day I visit, there are four well-attended events taking place: an Esol (English for Speakers of Other Languages) class, the opening of an exhibition, a book café and a workshop called Tips For Girls. The place is humming like a finely-tuned engine fuelled by tea, which appears every now and again as if from nowhere; on special occasions it is served in vintage china cups.

At the book café, a group of women are tucking into a lunch of oatcakes, crisps, dips and sandwiches as librarian Wendy Kirk talks about Kathleen Winter’s travel memoir Boundless. The munching stops when she starts to read, though, and everyone listens rapt to Winter’s account of her journey through the Northwest Passage, After the first chapter, the women swap tales of their own travels: on a cruise; to the Camino de Santiago in Spain; to a bird sanctuary on a remote Scottish island. There is no one-upmanship; just a sense of camaraderie.

Later, Kate McNab says she had a sleepless night worrying about the event. Many years ago, she helped found a women’s aid group in the north of Scotland. On her first trip to the GWL a week ago, she came across books that brought memories of that time flooding back. “It hit me right between the eyes, and I didn’t know if I liked it,” she says. “Maybe I’m a wee bit ashamed that I concentrated on my family and didn’t carry on [with the women’s aid group], but quite frankly I was drained,” she says. So how does she feel now about the book café? “The only other women’s groups I have been involved with were strident, but this is very warm,” she says.

The GWL has its roots in a grassroots organisation called Women in Profile, co-founded by Patrick as the 1990 City of Culture was taking shape. Back then there was a fear the flagship events would all be celebrations of male identity: the new Glasgow Boys, the shipbuilding and gang fights. Women in Profile produced its own events, including Castlemilk Womanhouse, a venture which took place in four empty tenements and was inspired by a 1971 project of the same name at CalArts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the Year of Culture came to an end, the group realised it had gathered an important social archive – artefacts, documents and books relating to women’s lives – so it started up a small volunteer-run library in a shop-front in Garnethill. For the first 10 years of its life, the GWL existed hand to mouth; there was a public appetite for its services, but funding was nonexistent. “I was looking through newspaper archives recently and I found the headline: “Glasgow Women’s Library may close after three months.” That’s how perilous it was,” says John who got involved in 1992. “I remember having to ask supporters if they would lend us money to pay the rent.” In 1994, the city council gave them two floors of a dilapidated building in Trongate and they launched a programme of public events. It wasn’t until 2000, however, that the GWL began to receive funding from Glasgow City Council for its lifelong learning programme which continues to form a core part of its identity today. As it continued to expand, it moved from the Trongate to the Anderston Library at the Mitchell Library and finally to Bridgeton. Today, it has 22 paid staff and 100 volunteers and is one of Creative Scotland’s 118 Regularly Funded Organisations for 2015-18.

This feat is particularly remarkable when you consider that it has taken place against a backdrop of austerity and the continued tendency to neglect female voices. Other organisations devoted to women’s history in the UK are struggling. The Feminist Library in London has been threatened with eviction by Southwark Council unless it agrees to an increase in its rent from £12,000 to £30,000. The Women’s Library was forced to relocate from its purpose-built home in a restored wash-house in the East End to the LSE after the London Metropolitan Museum said it could no longer afford to run it.

Meanwhile, a private enterprise in the East End, which had been billed as a women’s museum, turned out to be a celebration of Jack the Ripper. Its critics say it glorifies his acts of violence and the only women’s voices it contains are the screams which ring out as visitors walk round the attraction.

So why has the GWL flourished where others have faltered? In part, it must be related to the different political climate north of the Border. “What we’ve realised post-devolution is that our political leaders are much closer to our communities – I just don’t think that’s the same in England,” says John. “We are hugely lucky to have Scottish Government committed to gender equality at every level.”

But its success is also due to the hard work and prescience of those involved; the GWL realised early on the importance of having a strategic plan, a business plan and an equality, diversity and inclusion plan and this has helped them respond to need and demand.

Staff were also quick to understand the importance of embedding the museum in the community. As a national archive, the GWL was always going to be of interest to academics. But Bridgeton is an area of multiple deprivation. How were people with little cultural capital going to feel about it opening on their doorstep?

One thing in the GWL’s favour was that they were occupying a building the community feared would otherwise fall into ruin. And the renovation was designed to increase inclusion: ripping out the divisive front counter, removing grills from windows where possible and generally increasing accessibility. It is difficult to tell how many local people use it regularly, but it certainly isn’t intimidating. There’s no sense you’d need to identify as a feminist to be welcomed in.

If the GWL has a “magic ingredient”, it is surely embodied in Patrick herself. A curly-haired whirlwind, she has lost none of her passion for the project she has nurtured for quarter of a century. What drove Patrick through the difficult years – and still drives her today – is a belief that women ought to be encouraged to dream more, aim higher and have faith in their own abilities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It seems to me the aspirations for women are often very meagre,” she says. “After all, the film-makers of the future, the women who are going to be our next political leaders, have got to come from somewhere. Why shouldn’t it be the woman who has just walked through the door?”

In the evening, I stay on for Tips For Girls – an event which looks at the way women are encouraged to make themselves attractive. On a table lies a cluster of books such as Manners For Women which teaches the fairer sex how to curtsey, eat and even laugh. “There is no greater ornament to conversation than the ripple of silvery notes that forms the perfect laugh,” it advises. There are film clips too. One, from 1948, features fashion designer Hardy Amies telling a young woman how to dress. “Above all try to think what you look like to other people,” he says in a Pathé voice.

But then writer Margaret Montgomery talks about her novel, Beauty Tips For Girls, and everyone agrees: though the words may be different, the message remains the same. Women are still being made to feel too fat or too thin, too slutty or too uptight.

Earlier, McNab said one of the reasons she had become emotional was that she felt nothing much had changed since her days in the women’s movement. “My daughter still tells me she gets touched up in buses and trains as I was constantly,” she said.

At a time when pressures on women are still rife, it is refreshing to be in a building where women’s history takes centre stage instead of being sidelined; where books on feminism are on the main shelves, not hidden away in a gender politics ghetto; where difficult issues around sexuality can be freely discussed. And where there’s always a fresh cup of tea on the go.