The Duddingston woman who 'came back from the dead'

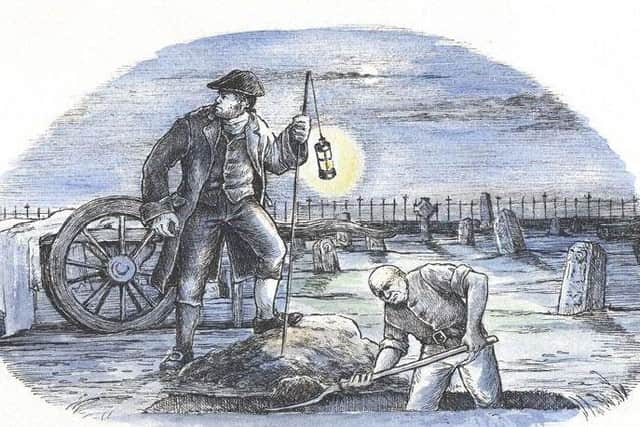

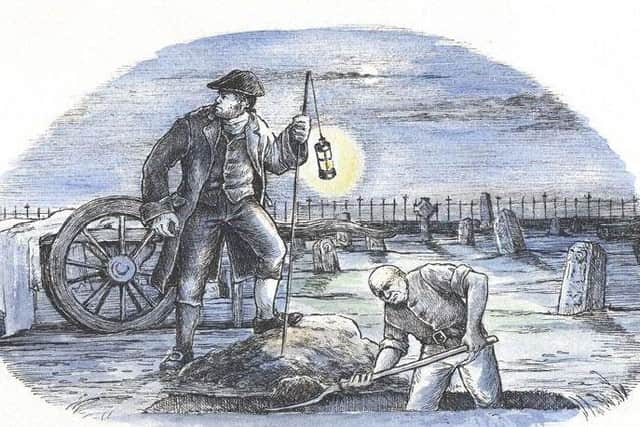

One report claims it was “with a sneeze” that she revived in her grave, where she had been presumed “as dead as Julius Caesar”, as two men attempted to raid her burial plot.

The story was printed in several publications during the 19th Century in light of the body snatching phenomenon, which centred around the sale of corpses for medical research with some bodies those of murder victims, killed for the cause.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile the era, which peaked with trial of Burke and Hare in 1828, had produced its fair share of ghoulish tales, the story of Ann Stewart is perhaps, on the face of it, the most fantastical of them all.

But still it persists, with a minister at Duddingston recalling the story within the last 30 years - and adding further details as to what happened to Ann after she “died”.

One version of the story was printed in the Dundee Advertiser on October 20 1898 which named body snatcher John Samuel and surgeon Dr Martin Eccles as being present in the graveyard.

Both had been involved in body snatching around Edinburgh with Samuel being transported in 1742 for his activities and Dr Eccles appearing in court the same year after a dissected body was found in his Netherbow surgery. The surgeon died in 1788.

The newspaper report of the “exciting adventure” in Duddingston Graveyard told of the two men going to “take up the body of a young lady in the name of Stewart”.

It added: “They were busy with their task and had nearly finished shovelling back the earth into the grave when to their untenable surprise, the corpse, which they had considered to be as “dead as Julius Caesar” suddenly electrified them with a resounding sneeze.”

They at once “dropped their tools and rushing toward the body, were amazed to find the young lady reviving.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe same story is repeated around 100 years later in Duddingson Kirk and Village: A Short History of the Parish, published in 1980.

It describes how the woman’s “hysterical screams” broke the silence of the night in Duddingston Churchyard.

One of the resurrectionists fled over the south wall, swam over Duddingston Loch and was never heard of again.

Another, named as Samuel in the account, escaped over the north wall, headed back to Canongate but was “captured on the Windy Gowl by some revellers from the Sheep Heid Inn.”

It is claimed he was hanged shortly afterwards.

The minister and the church beadle carried the girl to the manse where she was “revived and calmed down.”

“Her parents claimed the Minister had performed a miracle. He remonstrated but was referred to as the ‘minister who could raise the dead’,” the account added.

Ann fully recovered, married in the Kirk and had a son before emigrating to America with her family, according to the book.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt goes on to detail an account by Rev William Ramsay, described at the time of publication as the “current minister”.

He travelled to Maxton, North Carolina, a town largely built by Scottish immigrants, where he was shown the gravestone of a Scottish-born former minister.

Local tradition has it he was “born after his mother’s death,” according to the account.

The author claims it “would appear” that the little boy baptised in Duddingston Kirk became a minister in Maxton, North Carolina.

“Could this be pure coincidence?” the author said.

Burial records from Duddingston Parish show that five women with the surname Stewart, who were potentially in the same age range as Ann, died in the area between 1700 and 1850.

They include an Ana Stewart who died on April 10 1788.

Marriage records from the same period show that 11 women with the surname Stewart were wed in Duddingston Parish in the same 150-year period.

But none of the records throw up a match of women who were recorded as dead and married within the same period.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, it is not known if the death of Ms Stewart was ever recorded.

It has also been questioned why Dr Martin Eccles, mentioned in the Dundee Advertiser article, would be in the graveyard, when surgeons usually paid others to collect bodies.

It is possible that the names of both men were added, inaccurately, to the tale at a later date in order to give it an air of authenticity.

The truth about Ann Stewart, unlike the victims of Samuel and others, is almost certainly destined to remain buried.

A gatehouse built was built at Duddingston Churchyard in the early 19th Century to protect the graves from resurrectionists, whose activities largely faded out after the 1832 Anatomy Act which increased the number of corpses that could be lawfully used for dissection and teaching purposes.