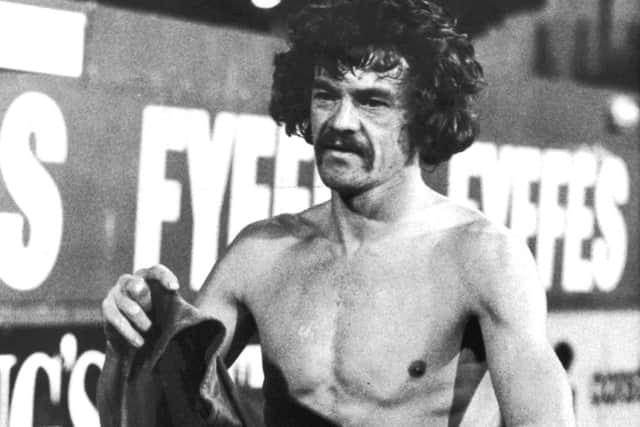

Chelsea legend Eddie McCreadie keeps his distance

He was performing at left-back for Chelsea when London, and the King’s Road, was the place to be. For a former East Stirlingshire player, it represented quite a step.

Towards the end of the 1961/62 season he was playing in the old Scottish Second Division. At the start of the following campaign, he was in the Chelsea first-team, having been offered a contract on the spot by Tommy Docherty after a Scottish league match. “And I wasn’t dropped again for 12 years,” says McCreadie.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was a permanent fixture in the Chelsea team for most of the 1960s and early 1970s. After he stopped playing he was then quickly promoted to manager. “I was only the tenth coach in the history of a club formed in 1905, that is a considerable compliment,” he notes, with understandable pride. Of these ten, five were Scots, in a further illustration of the club’s strong Scottish ties. It makes McCreadie’s long absence from Stamford Bridge in the time since he resigned his post, after winning promotion from the Second Division, seem all the more marked, and mysterious.

Originally from Glasgow, he has been born again in east Tennessee. “My accent might be a bit different, but I am still very much Scottish and very proud of it,” he says. “It’s just that I have not been back for some time,” he adds, with considerable understatement. The McCreadie of yore is still cherished at Stamford Bridge, however much the club has changed in the interim. To this day there is a bar called McCreadie’s in the Shed End stand. “I have never been, but I have seen pictures,” he says. “It is very humbling.”

Even now, a plaintively sung chorus of ‘Oh Eddie Mac, when are you coming back?’ is sometimes struck up by Chelsea supporters. It might be heard from the away fans today, when Chelsea take on Manchester City in the fifth round of the FA Cup. It is a competition McCreadie helped Chelsea win for the first time in the same city in 1970. A replay, held at Old Trafford, was required to settle the final against Leeds United, one that was watched by 28 million people on television. They looked on as McCreadie nearly decapitated his friend and compatriot Billy Bremner with a flying challenge (the clip is still popular on YouTube).

Remarkably, no penalty was awarded and Chelsea went on to win 2-1 after extra time. “I got a few knocks myself, though I did most of them to myself,” concedes McCreadie, who rates George Best as the finest player he faced in a list that includes Pele. “I did not take too many prisoners when I was playing. I enjoyed that side of the game, but I wasn’t dirty I didn’t think.”

If anyone wishes to own the jersey McCreadie wore in the first match against Leeds at Wembley then it is for sale on Ebay now, currently priced at just over £5000 and apparently given to the seller “by a family friend soon after the game”. It certainly helps support McCreadie’s claim that he does not own a single souvenir from his time in football; rather, he chose to give everything away.

“Chelsea called me about a year-and-a-half ago and asked if I could give them something like a jersey for the museum,” he recalls. “And I did not have anything! I had given everything away. Every shirt I had, every medal, I gave them away, don’t ask me to who. I just gave them to people. I had several things in my home in London that people could see. I felt after a while that when friends come to your home, you don’t have to throw in their faces who you are. Although I am very proud of my career, I had a change of heart, and I took everything down, and gave everything away.”

It is as if McCeadie has shed his skin. And in a way, he has. There is scant recent information about the former Chelsea and Scotland full-back, and you get the impression that this is the way he likes it. Last heard of in the United States, where he went to take up a coaching post with the short-lived North American Soccer League side Memphis Rogues, one thing was certain; he has not been seen at Chelsea for decades, not since he left his post as manager very suddenly in July 1977.

“It would take a combination of both Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot to get to the bottom of Eddie,” wrote Alan Hudson in a column in the Stoke Sentinel in 2002 after a visit to see his former team-mate. Hudson is of the few ex-Chelsea players to have seen him in person in the last 25 years. In the same column, Hudson noted that his old friend distinguished himself by being “a left-back and wing-back all rolled into one”. There was always something a little different about McCreadie. For example, not many players include a self-penned poem in their testimonial programme:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI’ve never felt so happy/And yet sad/I love you today/It might be cold tomorrow.

These lines could have been written about his relationship with Chelsea. They certainly seemed to anticipate a parting of ways, something that eventually happened after McCreadie led them to promotion two seasons after he was handed the reins at the already relegated club in 1975. The dispute is long reported to have centred on a company car. Bobby Campbell, his opposite number at Fulham, had one, and McCreadie did not. Even then such a scenario must have seemed faintly ridiculous; more so now, in view of the largesse with which the club is now associated. At the modern day Chelsea, it is likely that even the groundsman position includes such a perk.

“I know you have to ask about that,” he says, during a near hour-long, once briefly interrupted, conversation. When the battery in his cordless phone dies, McCreadie quickly calls back on his cellphone. Among the messages he wishes to put across is that the particular detail about a car is not accurate. “Everyone has that wrong,” he says. “It was nothing to do with a car. I am not going into details. I left because I resigned. It is assumed that I was not happy at the time, and no, I was not happy at the time. It was a disagreement between myself and the directors at the club, but these things happen. Am I mad at anyone? Of course not, but it was a decision I felt I had to make.”

“I love Chelsea, Alan,” he continues. “Please put that in. It is the greatest club in the world and every day I was there they treated me with the highest respect, took care of me, and as manager as well. We just had a disagreement that time. Things happen. There was a disagreement and I left because I felt it was the right thing to do. It was a difficult time for me, as it was for them.”

Chelsea are of course much changed since then. When McCreadie took over, they were on the verge of bankruptcy. But he appointed the then 18 years old Ray Wilkins as captain – “everyone thought I was a nutcase” – and delivered Chelsea back to the top flight, as he had promised. “It was not for me, it was not for anyone else, the most important thing was getting the club back to where they belonged,” he says. “I felt like my work was done. That was the most important thing to me in my life at that time.”

He stresses again that there are no hard feelings, and he still watches their games regularly from afar (with two Germans shepherds at his feet – one is called Mac, and the other Chelsea). So, will he ever come back to Stamford Bridge?

“That part of my life is over,” he says. “I will never say I will never go back there to see people. I would like to go back and see the crowd and say ‘hi’. Who knows? But I really have no desire to go and be involved again. It took up a lot of my life – and a lot of my private life. Sometimes enough is enough. I am glad it is behind me.”

“The reason that I don’t go back? Living in London I partied a lot there, same as most people did. My life has changed now. If I needed my ego boosted then I would fly back to London tomorrow.” What is it with Scots and their long exiles from London clubs? Speaking with McCreadie calls to mind Alan Gilzean, another enigmatic talent. Like Gilzean, McCreadie oozed charm, and lived life to the full in the capital. As with Gilzean, you sense a desire to leave this period behind, for whatever reason, although Gillie has of course finally returned to the fold at Spurs, and late last year was inducted in the club’s hall of fame. In McCreadie’s case, the fans’ wish to salute him on the pitch at Chelsea could prove a forlorn hope. He describes football, and everything that came with it, as having consumed him in London.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was surrounded by it, and people who would not let me get away from it,” he says. “But that’s okay, that’s the way life is. I am not complaining. I am glad it is over. I am not mad with anyone. You don’t see me in the papers too often. I don’t put myself around. I don’t care about that. I was a professional footballer when I was 17 years old. And now, Alan, I think: enough is enough. Enough is enough.

If McCreadie was not going to come to Chelsea, then Chelsea made an attempt to come to McCreadie, on a pre-season trip to California during Jose Mourinho’s first stint as manager. The club wrote to him, asking him if he would head west from Tennessee at their expense. He replied, thanking them for their gracious offer. “It was a wonderful gesture, how kind of them,” he says. “But I refused, I told them I was very honoured they had asked me, and that I would be thinking about the team, but I would not be going out to meet them.”

He isn’t being deliberately awkward, or reclusive. It is just that his life has moved on. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say it has changed, as he himself has explained. In more than one sense, McCreadie has stepped out into the light. He was baptised eight years ago, and hasn’t touched alcohol in nearly twenty. He plays golf and, having not so much as “washed a dish” until ten years ago, he cooks, sometimes for as many as 60 people. Now 73, he lives on a farm owned by his brother-in-law and where he is surrounded by 500 acres of fields; tobacco, pigs and cows are the main concerns. He and wife Linda, who he met in Memphis while she was studying law in the city, have built a house in the middle of the farm.

It is a long way in every sense from McCreadie’s childhood in Cowcaddens, Glasgow. He grew up on Cambridge Street in what he describes as a “slum”, and supported Partick Thistle. The Firhill club had him watched once but did not think he was good enough, and so he joined East Stirlingshire.

Perhaps more surprising than the admission he has not been back to Chelsea since the day he left the club is the discovery that he has not set foot in his homeland since attending a game at Hampden Park in the mid-Seventies. After all, he was a member of the iconic Scotland side who became unofficial ‘world champions’ by beating England in 1967, and played 23 times in total for his country.

That memorable game at Wembley when Jim Baxter, his partner-in-crime down the left, taunted his English opponents by playing keepie-up took place on McCreadie’s 27th birthday. But what sticks in his mind most vividly is standing in line for the national anthems before kick-off. “Like most games, I was always very nervous,” he says. “And it is even more nerve-racking when you are playing for your country. I remember thinking: ‘man, I wish they could get this game going, so I can get at it’. I looked across and I could see Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst, Alan Ball and thinking: ‘this is going to be tough’. And then I looked down the line and I saw Denis, Jim, Billy Bremner, John Greig, and I thought to myself: ‘what am I worried about?’”

McCreadie now draws the same reassurance from his faith. As with so many footballers, when his involvement with the game finished following a stint coaching in Cleveland, it seems that a void developed. “Things got really bad I felt at one time,” he explains. “Most people get down and get depressed sometimes in life and I am no exception. I got that way. I was looking for something and I could not find it. I needed some help. And I found the Lord Jesus. It sounds very simple, but it is a fact. I picked up the bible one day and I started reading it.”

“We go to church every Sunday like a lot of people do and during the week too,” he adds. “It is the most important thing in my life, let’s put it that way. It is nothing to do with soccer. If you are a Christian, that means you believe there is a heaven, right?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“And that means we are going to another world. And we are going to live there for thousands and thousands of years with the Lord Jesus, right? That is what the bible tells us. Is there anything more important than that? Is soccer more important? Is Chelsea? I don’t think so. There is nothing more important than that – if you are a Christian, that is.”

Having returned my initial phone call because he was worried it would have seemed impolite had he not done so, he is insistent about one thing. “You tell your friends over there that Eddie McCreadie called you back,” he says. He makes one last request. “If you run into any of these guys, Billy McNeill, John Greig, Willie Henderson, and I’m not even sure whether they are still alive, you tell them I said hello.

“You ever see any of them, please tell them that you were speaking to Eddie McCreadie and he just wanted to say hello.”