How sword and pestilence have previously denied Celtic and Ferencvaros a Budapest meeting with a brave club stance and extraordinary events following the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

Their current Europa League hostilities represent the third time the clubs have been drawn against one another in continental competition. Yet, past vagaries mean their meeting tonight will be the first time that they have squared up on Hungarian soil in UEFA competition.

Pestilence and sword account for those missed confrontations. And let’s hope famine and death never play major roles should the duo be paired in the future. It will be well remembered by all that the Covid-19 pandemic precluded a two-legged format being employed for their Champions League second round qualifier 15 months ago. And that Ferencvaros triumphed in the one-off tie staged at Celtic Park. Few, though, will be familiar with the extraordinary events prompted by Celtic drawing the Hungarians in the first round of the European Cup in August 1968, with the Budapest leg set for September 18. In no small part because the tie never took place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a turn of events expertly chronicled by the superb and exhaustive on-line resource on all matters Celtic that is The Celtic Wiki, a major fissure – involving Celtic, UEFA and the cluster of communist countries competing under its auspice – was triggered by the draw that proved a direct consequence of the Warsaw Pact invasion of communist Czechoslovakia on August 20, 1968. Then, the Iron Curtain was drawn further owing to the Soviets’ twitchiness over the liberalising agenda of the country’ leader Alexander Dubcek, whose reforms under the proclamation “socialism with a human face” were dubbed the Prague Spring. In order to prevent such blossoming in neighbouring Warsaw Pact countries, the Soviets sent in the tanks - just as they had in Hungary 12 years earlier.

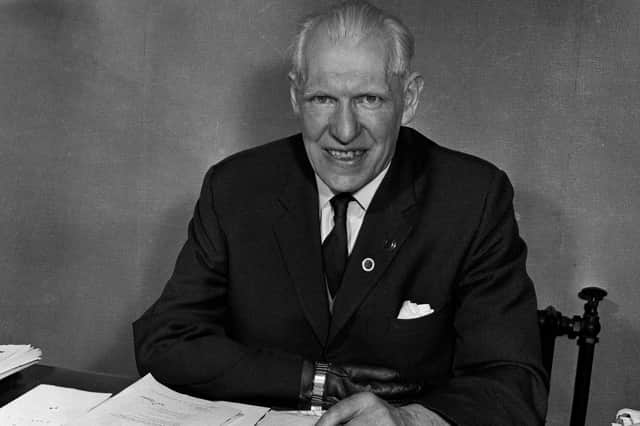

In total, 2,000 of them rolled into Czechoslovakia, with a quarter of a million troops from fellow Warsaw Pact countries the Soviet Union, Poland, Bulgaria and Hungary, invading the country to crack down on the political and cultural dissociation from Pact doctrines that had been set out by Soviet general secretary Leonid Brehznev, who ordered the occupation. Meeting pockets of resistance, 137 were killed with 500 injured in brazen manoeuvres that reverberated around the world. All the way, indeed, into the living room of Celtic chairman Bob Kelly, who watched aghast as this militaristic crushing of souls and spirits was captured in television images. In his subsequent autobiography, Kelly set out the actions that the scenes compelled him to take.

Celtic had an enduring affinity with Czechoslovakia, with former player Johnny Madden regarded as the father of the Czech game, and the club having undertaken one of the earliest cross-border trips in playing in Prague in 1904, then again in 1911, with Kelly’s father James and his brother Charlie in the party, before he himself had led the Celtic delegation in jaunts in 1964 and 1967. More pointedly, Kelly abhorred the invasion and had bitter experience of the meddling that flowed from the bureaucratic Soviet Union monolith following the, believed, dirty tricks suffered when Celtic, then defending the European Cup so mesmerisingly won in Lisbon in May 1967, were ousted in the first round of the following year’s competition by Dynamo Kyviv, two years on from a different outcome that followed the clubs’ meeting in the Cup Winners’ Cup.

Celtic’s objections to UEFA over fulfilling a Ferencvaros away tie set for September 1968, more than anything though, was a crusade borne of principle. As the Celtic chairman said: “It was one way of putting on record our moral support for the Czechs.” In a pronouncement that will tickle current Celtic ultras group the Green Brigade, on reflecting on the stance Celtic took, Kelly would also later state: “I wish I had a pound for every time it has been said or written that politics and sport do not mix – or should not mix. But with the emergence of sport, especially football, as an important aid to enhancing a country’s prestige in the world it is much harder to keep politics and sport apart.”

As an immediate first step to halting their trip to Budapast, Kelly, and Celtic, fused the two with a telegram sent to the UEFA Secretary, Hans Bangerter. It read: “In view of the illegal and treacherous invasion of Czechoslovakia by Russian, Polish and Hungarian forces and in support of the Czech nation, we, the Celtic Football Club, do not think that any Western European Football Club should be forced to fulfil any football commitment in any of these countries.”

Cue UEFA being sent into an almighty tizz. Celtic had real clout through their emergence as a footballing superpower but the governing body had no enthusiasm for antagonising the Communist Bloc countries within their auspice. Furthermore, the war crimes then being committed by the US in Vietnam had ensured there was no prospect of any military kick-back for the Warsaw Pact countries over their Czechoslovakia invasion. The Vietnam war provided them the ultimate ‘whatabouterry’ to fall back on...

Yet, Celtic’s name and standing led to the situation playing out differently in football circles. Support within Scotland for their demand of a redraw came immediately from Rangers, Hibs and Aberdeen - who followed Celtic in sending a telegram to the organisers of the Fair Cities Cup they were to compete in, then not run by UEFA. The governing body buckled as other countries backed the Kelly-led protest, and redrew the European Cup and Cup Winners’ Cup, with clubs from east and west kept apart in the first round. The outcry promoted clubs from the east to withdraw from European competition that season; the Polish FA doing so first, before clubs from Hungary, Bulgaria and East Germany followed suit. Then, just as the frist rounds were about to take place, the Soviet Union also took this course of action. They declared the redrawing of the first rounds as “unsavoury” and “an attempt to drag reactionary political tendencies into international sport.” The tournaments went ahead, in spite of these problems, and Celtic were paired with St Eitenne, who they would defeat on their way to reaching the quarter-finals, where they lost to AC Milan. Yet, their biggest victory that season unquestionably was off the field.

As Kelly, whose knighthood four months later many attribute to his stand, put it: ““Celtic will hold their heads high for what they did. If UEFA had ruled against us we would almost certainly have competed only under the strongest type of protest; we might well in the circumstances have withdrawn from the competition. There are things for Celtic more important than money.”

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.