'˜The Greatest' Muhammad Ali dies aged 74

No place better encapsulates the life and legacy of Muhammad Ali than the eponymous museum and cultural Center, as the Americans spell it, on the banks of the mighty river Ohio in downtown Lousville.

Yes, there are whole floors dedicated to his extraordinary boxing career, but there is much more to the Muhammad Ali Centre than just the Sweet Science, of which he was the greatest of all practitioners.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Center is emblazoned with these words of Ali’s: “For many years I have dreamed of creating a place to share, teach and inspire people to be their best and to pursue their dreams.”

The $80 million Center does just that, with a series of exhibitions featuring Ali’s core values of spirituality, respect, confidence, conviction, dedication, and charity. It’s all about human empowerment learned from a man who did it the hard way.

Two of the exhibitions show Ali’s worldwide appeal as they feature contributions from more than 5,000 people in over 140 countries. The Center also acts as the global headquarters for the Humanitarian Awards programme named in honour of Ali.

So where began Ali’s metamorphosis from mere boxer to global figure and exemplar of peace and understanding? It is not a long walk from the Center to the Second Street bridge across the Ohio where Ali famously instigated his own personal revolution by throwing into the river his Olympic light-heavyweight Gold Medal won in Rome in 1960. He said he did it because he had been refused service in a segregated Louisville diner. Many people doubted his story, until the medal was found in the mud of the river during a clean up two years ago - it meant that Ali had two Golds, the International Olympic Committee having sanctioned the issue of a replacement for The Greatest.

It was his claim to be The Greatest that first put white American on edge about the then Cassius Marcellus Clay jnr. It began as a piece of pure youthful braggadocio in the wake of his spectacular upset win over Sonny Liston.

By then Clay had begun to question the racism and segregation which was a way of life for black people in many parts of the USA and his conclusion would have devastating effects for his career and help to change his country.

In a whirlwind of events that truly shocked America and his fans everywhere, new champion Cassius Clay rejected what he called his slave name, set aside his Baptist upbringing and joined the Nation of Islam, becoming Muhammad Ali.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere’s no doubt that the racism he encountered drove Ali into the arms of an organisation that was on the lookout for black people to convert and become Muslims. He had met the charismatic Malcolm X and been converted to the Islamic faith as preached by Elijah Muhammad after whom he re-named himself.

It is hard to understate how detested the Nation of Islam was in the mid 1960s. They were seen as black supremacists, and managed to unite Christians, Jews and other Muslims in hatred of a group which now had the world heavyweight champion as its most famous recruit.

Some governing bodies tried to strip Ali of his title and licence to fight, and Ali responded in the ring by battering a haplesss Floyd Patterson almost senseless, taunting the former double world champion as an ‘Uncle Tom’. That was in 1965, the year that his friend Malcom X was assassinated for abandoning the Nation of Islam for a more mainstream Sunni form of Islam – a move Ali himself would make ten years later.

As if his conversion to Islam was not enough, Ali then refused to be drafted into the US military in line with the Nation of Islam’s policy that no black man should serve in the forces.

While still Cassius Clay, he had been assessed for the draft and classified 1-Y, meaning he could only be called up in case of a national emergency, which Vietnam was not. This was probably because of his poor literacy and numeracy skills, but suddenly, almost as soon as he changed his name, Muhammad Ali was mysteriously re-classified as 1-A, or ready for immediate service. This decision sparked Ali’s first stand on principle and some would say his greatest fight.

It was certainly his toughest, as he was taking on Uncle Sam. By now a civil rights campaigner as well as the most prominent black person in America, in early 1967 Ali received his draft notice and went along to his physical examination which he passed easily, but refused to be sworn in, citing his religious beliefs.

White America went mostly crazy, and the whole world was entranced by the world’s most famous fighter refusing to fight. “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong…no Vietcong ever called me nigger” he famously said. He was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in jail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe reaction across the world was extraordinary. Overnight Ali turned from a mere boxer to a figure of massive importance in the 1960s.

The Vietnam War was already on the way to great unpopularity, especially among American youth. It was the era of flower power and now there was a figure that black civil rights campaigners and young opponents of the Vietnam War alike could claim as their own.

Ali was 25 when he went to prison. He was soon released on appeal and eventually the Supreme Court ruled in his favour, but it took four years that might well have been the best of his career. Instead he talked and talked and talked, to black and white audiences alike, for civil rights and the need to end the Vietnam War.

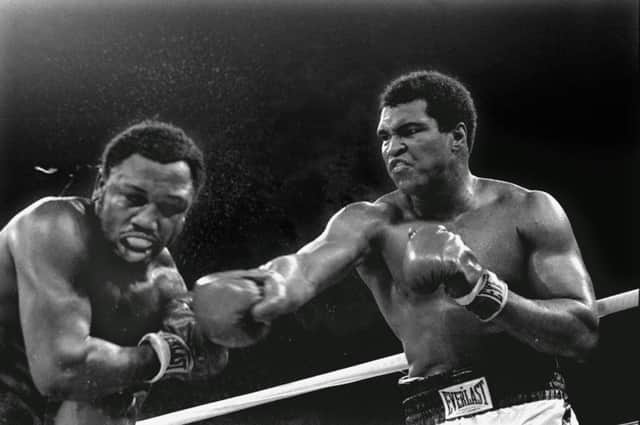

It has to be remembered that there was a very dark side to Ali, as shown by his shabby treatment of women, and in the ring by his humiliation of several fighters, including his great rival Joe Frazier whom he labelled an ugly tool of the white establishment.

Somewhere along the line, however, Ali changed and realised that his very fame could be a huge weapon in the second great stand of his life – his campaign for humanitarian causes, for justice, equality and peace. It was his diagnosis with Parkinsonism in 1984 which made him realise that he was living on borrowed time and he began to preach brotherly love in a powerful manner while the world saw his palsied shaking and wept for the Adonis reduced to a shambling wreck.

Ali’s risky negotiation with Saddam Hussein for the peaceful release of 15 American ‘human shield’ hostages in 1990 was perhaps his second finest hour outside the ring. And when America said sorry and appointed Ali to light the Olympic flame at Atlanta In 1996, the world willed him on to beat his disease and complete the task – which he did.

The man who came to transcend religious hatred, the great fighter who became a warrior for peace, will always be rembered, in the words of sportswriter Jimmy Cannon about another great black heavyweight champion Joe Louis: “He was a credit to his race…the human race.”