The mystery of the Edinburgh psychic who saw the face of Jack the Ripper

In his comfortable semi-detached Edinburgh home, Mr Scott had been having nightmares about the Whitechapel murders in faraway London, and he believed that in his dreams, he had three times seen Jack the Ripper. Twice, in July 1889, he had seen Jack standing in what looked like a small dispensary, like if he had been a ship’s surgeon. Mr Scott had felt strangely frightened of this sinister figure, who had fixed him with his steely glare.

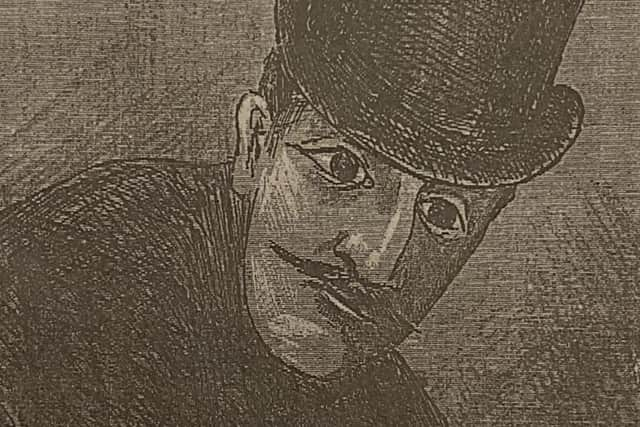

When he saw an announcement that Mr Stuart C Cumberland, a popular thought-reader and occultist who conducted the Mirror weekly newspaper, also had had a vision of Jack the Ripper, he eagerly bought the Mirror of July 29 to compare notes with the drawing made by this celebrated psychic. T Ross Scott was amazed to see that the man in the drawing, who had clandestinely claimed authorship of the Whitechapel murders to Stuart Cumberland, was an exact fit with the man in his dreams, apart from the colour of his moustache.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCumberland very much appreciated the support from his Edinburgh disciple, and published his letter in the Mirror of August 5. Dreaming about Jack the Ripper seems to have been a popular pastime in 1889: a lady correspondent of the Mirror had also seen the sinister Jack in her dreams, and later also claimed to have seen him when awake, sitting in a fashionable London church during evening service.

But the most exciting dream of Scott was still to come. On Tuesday September 10, he went to bed at 1.30am but was still awake at five minutes to three. He then fell

asleep, dreaming that he was walking along a broad street with tall buildings on either side. A tall, dark figure rapidly approached him, holding a large carpet bag in his right hand, which apparently he had considerable difficulty in carrying. It was the ‘ship’s surgeon’ he had seen before and associated with Jack the Ripper. As Jack passed Scott, he again fixed him with his steely glare, making it impossible for him to move.

The Mayfield Dreamer awoke at 11 minutes past five, struggling violently and feeling completely exhausted, although not exhausted enough to keep him from sharing, that very morning, his experiences with the readership of the Evening Dispatch. Although he had not dreamt of the ‘ship’s surgeon’ murdering any person, there was the mystery of the heavy carpet bag he had been carrying, and what Scott perceived as the temporal relationship of his dreams to some of the Whitechapel murders.

The name Jack the Ripper sold newspapers then as well as now, and abridged versions of Scott’s account appeared in the London St James’s Gazette, in the York Herald, the Dundee Courier and the Irish Times, among many provincial newspapers. The Ripper-busting Mayfield Dreamer was fast becoming a national celebrity.

Since one of the hallmarks of the much-derided discipline of Ripperology has been painstaking attention to detail, it is strange and blameworthy that although Jack the Ripper: The Forgotten Victims by P Begg and J Bennett briefly mentions Scott and his exploits, no person has ever published the background of the Mayfield Dreamer.

It turns out that Thomas Ross Scott was born in Edinburgh on June 5 1869, the son of the bank clerk Robert Thomas Scott and his wife Isabella. He took an early interest in spiritualism, conducting a thought-reading séance in Musselburgh in April 1889, to a disappointingly small audience according to the Musselburgh News. At the time he wrote

his letter, he was just 20 years old and a medical student, but prior to being driven from their desks by the Coronavirus, the staff at the Centre for Research Collections at Edinburgh University was unable to find evidence he graduated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the time of the 1901 Census, he was married to his wife Margaret and had the sons Robert, Percy and George, describing himself as a journalist. Scott moved to Glasgow in 1900 or so and stayed there for the remainder of his days. When he expired in 1950, from cerebral arteriosclerosis and hypostatic pneumonia according to his death certificate, he was described as a medical practitioner living at 47 Burnbank Terrace just outside central Glasgow.

It is the present-day consensus among the more reliable Ripperologists that the Whitechapel murderer had five victims and five victims only: his depredations on the women of Whitechapel ceased after the horrible murder of Mary Jane Kelly, in Miller’s Court off Dorset Street, on November 9 1888. Some dissenters have included Alice McKenzie, murdered on July 17 1889, among the true Ripper victims, but no serious student of the murders has suggested that the Ripper was still active as late as September 1889.

There was an interest in spiritualism and thought-reading at the time, with Cumberland becoming quite a celebrity conducting his own newspaper, with antics that

would today be called blatant quackery. Nor can the Mayfield Dreamer escape being tarred with the same brush, due to the séance he conducted in Musselburgh half a year before his brief pseudo-Ripperine newspaper fame: he was clearly an excitable character who ‘’saw things’ everywhere, and who believed in esoteric pseudoscience.

The newspapers of the time also had a fascination with thought-reading, the interpretation of dreams, and various other occult phenomena, explaining why the obscure account of Scott and his curious dreams became a national news story. The Face of Jack the Ripper, as revealed by the chimaeric visions of the charlatan Cumberland and his

disciple Scott, might just as well have been the face of the milkman next door.

Jan Bondeson is the author of Murder Houses of Edinburgh, published by Troubador, and Rivals of the Ripper, published by History Press (paperback edition out May 2021)

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.