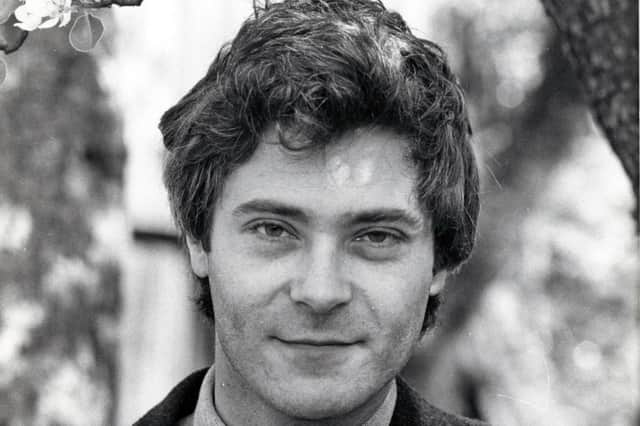

Scotsman Obituaries: Geoffrey Elborn, biographer of Edith Sitwell

Geoffrey Elborn was a biographer whose lives of Edith Sitwell and Francis Stuart attracted wide praise for their scholarship and readability.

Geoffrey was also passionately devoted to music, published a volume of poems at the age of 21 and reluctantly wrote a life of Princess Alexandra. His latest work, a history of vodka, came about through his interest in Russia, which dated back to his teens when he read Dostoyevsky for the first time.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was born in Edinburgh in 1950. As a baby Geoffrey and his twin sister Gillian were adopted by Arthur Elborn, an architect, and his wife Janet, a schoolteacher.

Aged seven he contracted whooping cough and spent several months in a Glasgow hospital. His parents were warned that if they did not move to an area with cleaner air their son would die.

The family promptly relocated to Airth, a small former port on the river Forth near Falkirk.

A lonely teenager, Geoffrey gained solace by writing to anyone interesting outside his village – musicians, artists and politicians. His father was annoyed when his own copy of a John Steinbeck novel arrived through the letterbox signed by the author.

In time the artist Laura Knight and politician Clement Attlee became close friends and in 1967 Geoffrey’s school friends bet him that he could not obtain the autograph of Brigitte Bardot, who was filming in Scotland at the time. Geoffrey took up the challenge and in his best schoolboy French phoned all the likely hotels, asking to be put through to his “dear friend Miss Bardot”.

Eventually he was connected and, abandoning all pretence, explained the situation to the French star.

A few days later a large, printed photograph of Brigitte in the semi-nude arrived in the post with “To Geoffrey with love from Brigitte” scrawled across her breasts.

On his first visit to London in July 1967 he visited Laura Knight, took tea with Clement Attlee, and, through Mary Wilson, was treated to a tour of Downing Street. He also managed to waylay TS Eliot’s widow in the street.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeoffrey attended Larbert High School, where he stood as a Liberal candidate, receiving a rosette from Jo Grimond.

On leaving school, instead of applying for university, Geoffrey was briefly a cub reporter at the Falkirk Herald, where he covered football, which he knew little about, and the cinema.

He then took a job as a library assistant in Edinburgh. Here he continued to befriend poets, including W H Auden (who told him that literature and librarianship do not mix), John Betjeman, Kathleen Raine and the Orkney poet George Mackay Brown. Sir Compton MacKenzie became another close friend.

On one occasion Geoffrey took a call from Henry Moore at his library, which caused consternation among his more senior colleagues. At the age of 26 he left librarianship to take up a place at the University of Leeds, where he read English and Music.

Geoffrey’s first book, a biography of Edith Sitwell, appeared in 1981, two years after he graduated, and in the same year that saw another life by the older and better-known Victoria Glendinning.

His book received good reviews, many critics preferring the younger writer’s more personal view of Edith and her brothers that had been built up over several years.

His next book was a life of Princess Alexandra, which he did not want to do, but was obliged to carry out as part of his book deal. It brought him some of his most far-and-wide fans, including an Inuit woman in Canada.

I first met Geoffrey late in 1982, soon after this biography had appeared. The artist John Piper, then General Editor of the Shell County Guides series, urged me, as author of the recently published Shell Guide to Hertfordshire, to approach Geoffrey, who was recruiting contributors for his planned tribute to mark Piper’s 80th birthday. Geoffrey’s admiration for Piper, which matched my own, had probably came about through the artist’s association with the Sitwells, and particularly Osbert, whose autobiography, Left Hand, Right Hand, he had illustrated.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter our initial meeting Geoffrey and I became firm friends and in the 40 years of mainly pub conversations that followed he unfailingly provided a stream of often hilarious literary anecdotes, sometimes accompanied by expert mimicry (anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer was a favourite) which dated back to his dealings with those artists and writers in his teens and early twenties.

Although we had long-standing disagreements on the merits of Edith Sitwell and Geoffrey Grigson as poets (I was a devotee of Grigson, who had taunted Edith in New Verse), Geoffrey remained a steadfast supporter of the latter.

Although a committed socialist from his late teens, Geoffrey’s next biography was a sympathetic life (the first) of the highly controversial Irish novelist and polemicist Francis Stuart, then 87.

Choosing such a subject might have proved dangerous for Geoffrey’s growing reputation. Stuart disliked democracy, had been a gun-runner and in his broadcasts on German radio during the Second World War had professed an admiration for Hitler. He also had a violent streak and had physically abused his wife.

However, Geoffrey’s thorough scholarship and obvious devotion to the task of making a case for the rehabilitation of a “difficult” though talented writer was obvious. Francis Stuart: a Life was widely praised and is still cited as the best work on its subject.

Geoffrey seems to have been attracted to “difficult” or controversial writers. He became intensely interested in the novelist Patricia Highsmith after accepting a commission to look after her in Switzerland.

Although her death terminated this contract he went to her funeral and spent a good deal of time interviewing people in her life. However, for various reasons, Geoffrey decided to abandon any plans for a biography.

Geoffrey’s next book – a history of vodka – was a departure, but its focus on the social history of the spirit over the centuries reflected his passion for Russia. At his death he was researching a work on Russian-Scottish relations over the centuries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis first love, however, was music, and particularly the piano. He once taught Music at the City of London School for Girls and was surprised when the girls got out their wool and expected to knit in his lessons. Years later, whilst ranting about Strictly Come Dancing, he was shocked to discover that presenter Claudia Winkleman was one of his old girls.

His friendship with Malcolm Williamson, the Master of the Queen’s Music, which had begun in the early 1970s, lasted until the latter’s death in 2003.

During the last year of his own life, Geoffrey devoted most of his time to completing the huge task of archiving the papers of Williamson, his publisher Simon Campion and the composer Elizabeth Poston, which were housed in Williamson’s former home in North Hertfordshire.

Geoffrey is survived by his partner, the museum educator Mark Watson.

Obituaries

If you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), or have a suggestion for a subject, contact [email protected]

Subscribe

Subscribe at www.scotsman.com/subscriptions