Sally Magnusson on how music can treat dementia

“It’s a lovely day tomorrow

Tomorrow is a lovely day

Come and feast your tear-dimmed eyes

On tomorrow’s clear blue skies

If today your heart is weary

If every little thing looks gray

Just forget your troubles and learn to say

Tomorrow is a lovely day”

From Irving Berlin’s It’s A Lovely Day Tomorrow

Dementia was robbing Sally Magnusson’s beloved mother Mamie of words and memories, yet the opening bars of one of her favourite songs would see her take up the refrain and be immediately transported back to a place where the confusions of this cruellest of diseases would fade and she would regain, for a time, something of herself.

As the disease progressed, the BBC Reporting Scotland anchor and her family felt they were losing their mother bit by bit, memory by memory. However, music still had the power to ground her, and they reached for the repertoire she had been singing them all her life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSongs weave their lyrics and melodies throughout the memoir Magnusson has written of her mother, a project that also inspired her to set up a charity called Playlist for Life. There’s everything from ragtime to Mozart to Gaelic airs, and paper and comb renditions of The Wee Cooper O’ Fife. As well as Irving Berlin’s It’s A Lovely Day Tomorrow, there is Vera Lynn’s The White Cliffs Of Dover, the roustabout Ragtime Cowboy Joe for upbeat moments, and Scots lullaby Dream Angus when a calming air is needed.

“If anyone had warned me how much the rights you have to pay cost, I might have thought twice about including them all,” laughs Magnusson, all sparkling blue eyes and elegantly coiffed butterscotch and cream hair.

“Mum sang anything and everything. She was brilliant at harmonising, coming in below the melody and swooping around, and before you knew it you were partaking of something rather fun.”

Mamie Baird Magnusson was a dab hand with the mouth organ too, coming from a time and place where people made their own entertainment. In her Rutherglen council house her dad had a violin and there was an inherited organ too.

“Music was very much part of that working class culture,” says Magnusson. “Hogmanay, family get-togethers, weekends, they were always social and there was always singing.”

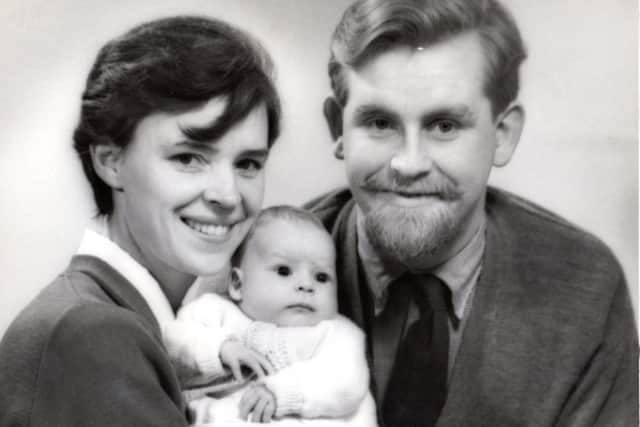

Mamie’s life had always had a soundtrack, usually provided by her, but it was through words she made her living. At 17, the smart working-class lass wrote her way into a job in the male-dominated world of post-war newspapers, where she earned more than most male journalists, first at the Sunday Post then with the Scottish Daily Express. Vibrant, intelligent and sparky, it was in the Express’s newsroom that she dazzled Magnus, younger and posher and earning cash to fund his academic ambitions. A day in Mamie’s company was enough to convince him that journalism was more exciting, and the couple married in 1954. When Mamie left the workplace to have Sally, the first of five children, Magnus inherited her job as lead feature writer.

“I only married her for the job,” he would quip later.

We were used to seeing Magnus in our living rooms, for 25 years the question master on BBC’s Mastermind, but in the book it’s Mamie who is the star. Here is Mamie’s glorious life lived large, and the stories, memories and confabulations she gave her children live on, thanks to her daughter having inherited her way with words. She nails her mother’s quiddity and gives us her vaulting bins in Buchanan Street, stopping the Queen in her tracks with an impromptu rendition of Will Ye No Come Back Again at a douce Edinburgh gathering, and getting a fur glove stuck in the bell at Balmoral – she leaves it to clang while an engineer is summoned, and she is given a scoop tour of the house being prepared for the newlywed Queen and Prince Philip.

She’s there at Magnus’s right hand, editing his speeches and writing chapters of his books, dashing off articles and letters, hosting gatherings and parties right up till his death in 2006.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe and his daughter never discussed what in retrospect were clearly the symptoms of early dementia in Mamie, although he did find a word for how she seemed. “Distraite”, he called it. Sally calls it a slippage of moorings and instinctively begins to write things down – to Mamie’s delight.

“I started writing it to keep hold of my mother, because she was beginning to change and this is a book about memory and I wanted to remember her. I didn’t want it to come across as a misery memoir,” says Magnusson. “It’s an affirmation of life and love and family and the continuing individuality of people with dementia. I wanted all these things to come across.

“It might simply have stayed a collection of private memories for the family if it hadn’t been for the fact I began to realise what an enormous social phenomenon we were part of and how bewildering and lonely it was, and how many other people out there were feeling the same way. I was just driven by this thing that we need to talk about it, and share it,” says Magnusson.

“I thought, we have a story here that applies to every family. We’re every family, I’m every woman and I probably have a journalistic duty as much as a moral duty to see if I can raise these issues. I don’t claim to do any more than just raise issues that society needs to think about. And we are thinking about it more now.”

I ask Magnusson whether she worried about her book becoming a political football, since it discusses issues such as acute care in hospitals and calls for more support in the home to allow people to look after loved ones there.

“For artistic reasons the story of my mother had to be central and anything else came off that. As soon as you go into any one of those issues in any depth it begins to be the Scots are doing this, Wales is doing this, England’s doing that and reports coming in here and there. I could have done another entire book on that. Also, with my other hat, I work for the BBC, and I’m not at liberty to campaign on social issues of any sort, although there are elements of me saying this needs to be thought about. But it’s not me issuing calls to the government.

“When I was in the middle of it all, I was hunting around for things to read from people with the same experience, for something to help validate myself, that maybe I’m not such a bad person – everybody goes through this. And if my book achieves that, that’s as much as I can hope – that people won’t feel so alone.”

After Mamie fell and broke her hip in 2009 and ended up bewildered by the hospital experience, Magnusson and her siblings vowed that their mother would never be admitted again, and they managed to care for her themselves until the end in April 2012.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I don’t say we did this and everybody else should do it. It’s not possible for everyone. It’s hell of a difficult and you do what you can in the circumstances and with what life has allotted you,” says the 58-year-old.

Was there a cost to caring, I ask.

“The cost was worth it. There’s always a cost to loving. It’s not just loss, it’s also gain,” she says.

What did Magnusson gain from caring for her mother? She pauses for the first time, her articulacy stalled as she looks into the distance, the past, and remembers.

“I gained everything. I gained her.”

As the other elements of Mamie’s life faded and the words became harder for her to find, the tunes and singing continued. For Magnusson, music is the one thing dementia cannot destroy – “the past embedded in amber”, as she puts it in her beautifully eloquent and honest book.

“It wasn’t that one day we woke up and thought we must start singing with my mother: she was always singing. But we gradually realised that as her grip on a lot of things loosened, her connection to songs was as strong as ever. When words became difficult and she was finding it hard to express herself, singing engaged her. Then the words would rise unbidden and there was this sense that she had these abilities still to do something better than anyone else – my own voice isn’t pleasant.” Magnusson grimaces.

“Also, there was clearly something neurological going on, because after singing for a while she was much more alert. It was taking her back to a place of familiarity and belonging, achievement and good memories. So we would strike up a song and sing them over and over, to the point where I thought if I have to sing White Cliffs Of Dover one more time I’m going to scream! I’m not proud of my own impatience now. Why couldn’t I sing it one more time?” she says.

Later, Magnusson wished she’d thought to put all of Mamie’s favourites on an iPod, a lightbulb moment that sparked the Playlist for Life charity she set up soon after her mother’s death at the age of 86.

The aim is to offer those with dementia their own bespoke playlist. Not only does compiling it provide beneficial interaction, playing detective and tracking down a loved one’s favourites, but it is hoped it will provide a non-pharmaceutical therapeutic intervention in the treatment of dementia too.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The Playlist works on several fronts,” says Magnusson. “Firstly, we are simply trying to tell people that everyone has a playlist of their lives and it could help them get through the difficult times ahead with dementia. We’re giving guidance in ways to make one, and developing a training package for care givers and volunteers in care homes so that they can cascade it out to people working with those with dementia. We hope also to develop training for individual family members.

“We’re collecting used iPods and handing them out, hoping schools might take this up. Teenagers can speak to gran or grandad and help get their playlist together. What were the hymns at their wedding, were they in a choir, what did they listen to when they went dancing? It’s all about the connection, connecting people and music and memories inter-generationally,” she says, warming to her theme.

“The process will personalise this person who is becoming progressively depersonalised by dementia. There’s an erosion going on, a dehumanising of them by society, that’s nothing to do with the disease but arises from the way we treat them. We can help that by bringing their personality and their past to the forefront again.”

Another element of the charity is a collaboration with Glasgow Caledonian University to apply for research grants to evaluate the use of playlists as an alternative to pharmacological intervention for all forms of dementia.

“If it can be evaluated properly, not just the efficacy but the economics of it, this could be really useful for the future. There would be a massive saving, on the cost of the drugs themselves, but also because someone not on drugs is less likely to fall or go into a terrible new spiral of illness,” says Magnusson.

“In US care homes where music and memory techniques are used, anti-psychotic drugs have been reduced by 50 per cent, but we need proper evaluation. If it goes ahead, the research done in Scotland would be world-leading.”

The idea for the charity came after Mamie’s death, when Magnusson was putting the book together. Much of it was written in the form of letters to her mother, jotted down after Mamie’s diagnosis and the authenticity of the carer’s voice and experience shines through. Magnusson writes with honesty about how she “is permanently tight with exhaustion and low on patience. No time to stop, never a chance to clear my mind. I am losing my grasp of a swaying stack of priorities: the children, the husband, the broadcasting, the mother whose needs dominate my week, the sisters who are left with more to do if I don’t play my part, the brother, grieving for his wife, whom I too rarely see, the friends who never hear from me”.

There is wry humour in the face of adversity too, with Magnusson recounting how Mamie introduces her to her own sister with the words, “Now, do you two know each other?”, and on another occasion, after a visit from grandchildren: “When did you start to take an interest in these people?”

“They’re my children,” replies Magnusson.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLater, however, Magnusson’s journalist training kicks in and she begins questioning the who, what, when, how and why of a disease that is exploding into an epidemic. She interviews experts and academics, nurses and carers, and the book becomes a call for change in the way we treat those who suffer from dementia.

There are 35.6 million people with dementia across the world, with an extra 7.7 million cases predicted every year, and some 800,000 in the UK. The World Health Organisation estimates one new case every four seconds. That’s another case in the time it took you to read this paragraph. Dementia care costs the UK £23 billion – more than the cost for stroke, heart disease and cancer combined. One in three people over 65 will die with it.

“I began to think, there’s something here that could be of use to others. It’s all very well having a moving story, but it needs more journalism to it. There’s a story about how we treat people with dementia and how we don’t treat them, and some of the ways ahead. The music thing had been at the back of my mind and, wondering if there was somebody I could go and interview, I stumbled upon this US charity, Music and Memory. It was a eureka moment. I contacted them and discovered no-one in Britain was doing it.”

“That’s when I said, ‘Somebody really should sort it’, then ‘Oh no, I shouldn’t have said that’ – I had so much else on my plate,” says the mother of five. “Anybody who knows me just hoots with laughter that I’m in charge of a website, but we went through all the business of starting up a charity and building up a team. It’s beginning to take off now. Alzheimer Scotland is going to provide us with a development worker and Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland is interested.

“We want to start people thinking about their playlists now – it’s great fun. Graham Norton has done his list for us, and some of the Downton Abbey cast. Ideally you’d want about 200, some uplifting, some comforting. Because you have dementia doesn’t mean you want to hear the same tune all the time. Not everyone in a care home likes Daniel O’Donnell all the time.”

So there’s no Daniel O’Donnell on Magnusson’s list then?

“I literally took the first five that popped into my head. There’s Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto, which makes me think of decades of not quite learning to play the clarinet, and a song from Guys And Dolls, after hours spent listening to a teenage son practising for the part in my kitchen,” she says. “I hear it on the radio, and I’m right back there.”

To see the rest of Magnusson’s playlist, visit the Playlist for Life website. You won’t be able to stop yourself thinking of your own. And one day you might find yourself listening to it again and thinking, to quote Mamie, “Thanks for the memories.”

@JanetChristie2

Where Memories Go: Why Dementia Changes Everything, by Sally Magnusson, Two Roads, £16.99, is out now

Playlist for Life, www.playlistforlife.org.uk