Rachel Ormston: Death penalty opinion hangs in balance

There have been no state executions for murder in the UK for half a century (the last execution in Scotland, of Henry John Burnett, took place in August 1963 in Craiginches Prison, Aberdeen). Yet it remains a subject on which public opinion is deeply divided.

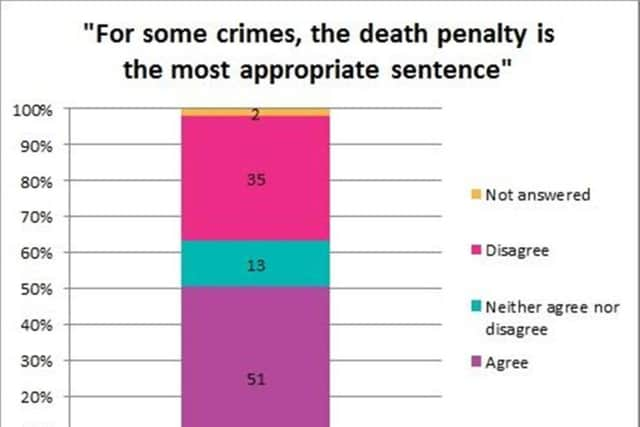

According to ScotCen’s latest Scottish Social Attitudes survey, around half (51 per cent) of people in Scotland still agree that ‘For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence’, while around a third (35 per cent) disagree and a fifth are unsure or say they ‘neither agree nor disagree’. Views in Scotland are broadly similar to those in Britain as a whole – in 2014, 48 per cent of people in Britain agreed with the death penalty for some crimes, while 35 per cent disagreed (British Social Attitudes 2014).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSupport for the death penalty in Britain has dropped in recent decades – from 74 per cent in 1986 to around half now. But it remains the case that, in both Scotland and Britain as a whole, more people agree than disagree with capital punishment.

Moreover, surveys that have asked about use of the death penalty for more specific crimes have often found even higher support – for example, a 2009 MORI survey found that 62 per cent thought the death penalty should be an option for child murder.

Of course, a criticism of survey data based on one or two questions about the general principle of capital punishment is that they do not force respondents to confront the details that might apply in a specific situation. And there is some evidence from research carried out in the US that people’s views of the death penalty may change when they are asked to consider ‘real life’ cases – for example, support for the death penalty for a violent murder fell considerably (although still not below half) when people were told the offender had experienced abuse themselves as a child.

However, capital punishment nonetheless stands out as an issue on which the opinions of the British public and politicians have apparently long been at odds. There have been numerous attempts since 1985 to reintroduce capital punishment in the UK (including a bill for England and Wales as recently as 2013, though this with withdrawn without progressing through parliament).

In each case, MPs have voted against its reinstatement.

Whatever your personal view of capital punishment, this apparent disjunction highlights questions over what the relationship between politicians and public opinion ought to be. Should parliamentary democracy be about reflecting the views of the public as closely as possible? Or should politicians lead based on conscience, evidence, or other considerations, even when this may involve going against public opinion? Rachel Ormston is Head of Attitudes Research, ScotCen Social Research.