Obituary: Jack Webster, Scottish journalist who ghosted columns for Muhammad Ali

Jack Webster described himself as “a wee boy from Maud” who departed his Aberdeenshire home for newspapers, and in so doing, interviewed world figures and developed a lifelong love of the United States.

The lure of the silver screen took him to Hollywood, Bel Air and Beverley Hills, as a regular passenger on the fabled Queen Mary and her sister ship Queen Elizabeth. In 1988, in a final farewell to both vessels, he boarded the Queen Mary at her permanent dock in Long Beach. California, while in Hong Kong he sentimentally sailed over the grave of the sunken Queen Elizabeth.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis idiosyncratic manner in relating a story won him Bank of Scotland Columnist of the Year in 1996, and – more surprising to his fans who knew him from early times – made him UK Speaker of the Year. This latter honour recognised his astonishing achievement in later life in overcoming a speech impediment so severe that the term “a chat with Jack” became code for a long spell of difficult listening.

Jack’s soft Buchan voice and innate courtesy opened doors to the famous and the infamous, from Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Paul Getty, George Best and Pele to Sophia Loren and Elizabeth Taylor, not forgetting Christine Keeler of the Profumo scandal.

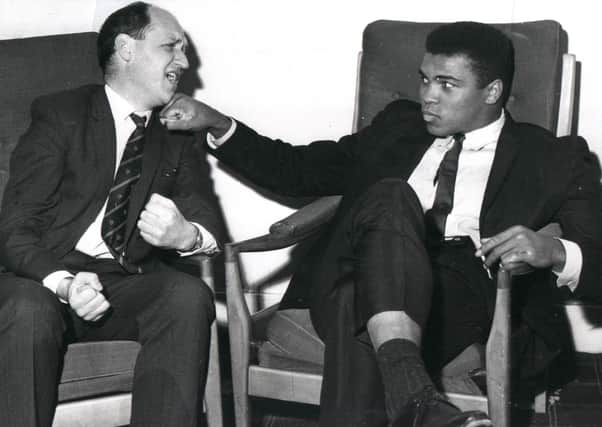

A keen ballroom dancer – he’d conclude so many tales of social events with “…and then we danced the night away” – that he went to Hollywood and met up with Ginger Rogers. At age 35, he ghosted for Muhammed Ali, and during a spell in the New York office of the Daily Express he interviewed the legendary Broadway composers Irving Berlin and Richard Rogers.

It was Jack who ran the elusive Charlie Chaplin to earth for his prize interview. Knowing that the Little Man holidayed regularly in north Scotland, Jack tracked him down to a hotel in Banchory on Deeside. No, his wife Oona insisted to Jack, Mr Chaplin would not be giving interviews, end of story. Jack had other ideas, and for three days sat in the lobby, apparently engrossed in Chaplin’s biography.

When the great man emerged briefly, Jack moved in. Would he kindly autograph the book? Chaplin paused, and Jack produced several other copies, also for signing. Jack held Chaplin’s attention long enough to remind Charlie that the great man had once appeared at the Tivoli Theatre in Aberdeen. Would he like to see the place again?

With a photographer already in place, the story appeared in the Scottish Daily Express of Chaplin and Webster together outside the Tivoli.

Jack – christened John, and the third John in three generations – was born in Fedderate Cottages in Maud, in the heart of Buchan, then home to the largest weekday cattle market in the UK, and where his father John was auctioneer. John never regarded Jack’s journalism as a real job until one day Jack showed his payslip…..more than twice what the Old Man was making.

Educated at Maud School, Jack gained a place at Robert Gordon’s College in Aberdeen, and took up the pipes. But a bout of rheumatic fever and a difficult headmaster saw him leave school at 14, and he started in journalism with the little Aberdeenshire weekly Turriff Advertiser.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe moved to Aberdeen with the Press & Journal before packing his bags in 1960 to join the Scottish Daily Express, It was an era when journalism was flourishing and the Scottish Daily Express held sway as possibly the most powerful opinion-former in the land.

With colleagues such as Mamie Baird, Jack McGill, Magnus Magnusson and Charles Graham, Jack’s work poured forth, and he proved himself at home whether in Scotland or San Francisco.

His 18 books range from his memoir series Grains of Truth, to the biography of the world’s best-selling novelist Alistair MacLean, to histories of his beloved Dons, his adopted Aberdeen, and indeed, Robert Gordon’s College, the school which so spectacularly failed him.

It proved more than pleasant irony when, in 2004, he gave the Founder’s Day oration at his alma mater.

Adapting to a new medium, Jack gained Bafta nominations for his BBC television series The Webster Trilogy, the first of which, Webster’s Roup, told the emotional story of the auction of the family farm of Honeyneuk by New Deer.

Aberdeen University awarded him an honorary degree in 2000, with a doctorate from Robert Gordon University eight years later. For services to journalism, Dr Webster gained the British Empire Medal in 2012, an honour long overdue in the eyes of his many friends, given that he had personally funded the saving of the piano on which The Northern Lights of Old Aberdeen had been composed by Mary Webb, an English lady in London who in her lifetime never visited Aberdeen.

The song, now the anthem of the Granite City, was written by Mary for a homesick Aberdonian girl who worked beside her in a hospital kitchen. Jack also successfully lobbied for the long overdue knighthood given to Dr John Brown, managing director of QE2 shipbuilders John Brown in Clydebank, and whose drawing instruments he had used when working on the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth.

Possessed of a singularly fluid writing style that could almost appear languorous, the reality for Jack was that his work was carefully crafted.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe sought inspiration from Lewis Grassic Gibbon (James Leslie Mitchell), whose writings he first encountered in the 1950s while working in the very reporters’ room of the Press & Journal in Aberdeen which Mitchell himself had used a generation earlier.

Jack wrote: “Reading Sunset Song not only opened my eyes to the true worth of rural life around me, but taught me more about the art of writing than any other influence”.

As colleagues, he had Gibbon’s one-time associates, Cuthbert Graham, George Macdonald Sr and George Fraser.

Jack came to know Mitchell’s widow Ray, brother John, children Rhea and Daryll, and not least Alexander Gray, the Arbuthnott dominie who first spotted Gibbon’s talent in 1913.

All this created Jack’s desire to put the writer on stage “to speak for himself”. One autumn night in 2007 in Gibbon’s Kincardineshire village hall in Arbuthnott, it happened, with Vivien Heilbron as the Narrator and husband David Rintoul as the novelist.

At the emotional conclusion, the audience rose in standing ovation, and when Jack was persuaded on stage, he stood there, tears running his face, confessing “This is the greatest moment of my life”.

Reminded that he’d said something similar in Gothenburg in 1983 when the Dons won the European Cup Winners Cup, Jack gently pointed out that Gothenburg had been “the greatest night of my life”.

Jack was predeceased by his wife Eden in 1990, and is survived by his three journalist sons, Geoffrey, Martin and Keith.

GORDON CASELY