Obituary: Graham Stewart, Scottish silversmith whose work graces Holyrood parliament building

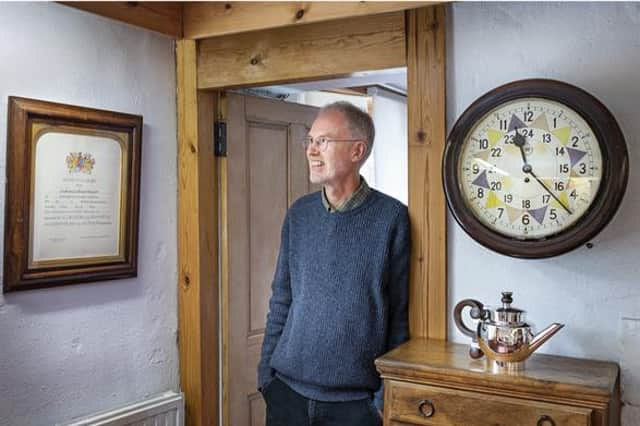

Graham Leishman Stewart, who has died aged 65, was one of Scotland’s foremost gold and silversmiths of his era.

The most prestigious of his many commissions is a large abstract silver sculpture displayed in the Main Hall of the Scottish Parliament. It is arguably the most viewed piece of modern silver in Britain today.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBorn at Bridge of Allan in 1955, Graham was educated at Dollar Academy (1960-73). His father, William Morrice Stewart, an industrial designer, was a leading influence in his life as he had a keen interest in silversmithing.

Indeed, when the lecturer who ran the local silversmithing evening class he attended retired, he asked Mr Stewart to take over.

Graham would periodically sit in on the classes his father taught. At the Academy his Art Master suggested he apply to Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen. He did, but was not sure whether he would be accepted, so he sought summer work experience with Norman Grant, the Fife jeweller.

Gray’s accepted Graham and with encouragement from Grant, he seized the opportunity.

From 1973-77 he studied for the Art and Design Diploma and in his penultimate year was a finalist in the Young Designer of the Year competition.

A one-year Art and Design Post Graduate Scholarship followed. Malcolm Appleby asked Graham to help him at weekends at Crathes.

Malcolm’s forte was engraving, so Graham added this faculty to his skill bank. Before graduating he spent the summer obtaining further work experience with the award-winning London jeweller Roger Doyle.

His parents had moved to Dunblane and Graham decided to put roots down there too.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith the help of the Scottish Development Agency, his father and brother Iain, an engineer, Graham began renovating a derelict building in the town.

Initially he concentrated on making jewellery and undertaking outwork for other silversmiths.

An early range of jewellery included a series of mainly silver bird brooches that proved popular. Their simple stylised forms had an indefinable quality that was charming.

During the 1980s Graham’s reputation spread and the commissions rolled in.

His output ranged from hand-wrought spoons to maces; from hand-raised quaichs to a Bishop’s crozier and from boxes to vases.

In 1986 through to 2018, when he became unwell, he attended the annual Goldsmiths’ Fairs in London. He was a very popular exhibitor and built up a strong international clientele.

Graham’s inspiration was mainly nature; his work does not replicate what he saw, but is organic.

Nature’s influence fed itself into his drawings seemingly intuitively. On one occasion he remarked to his wife Elizabeth that the couple’s whippets had “not yet made it into silver”. She pointed out some jugs – intuitively, they had!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are two objects that I particularly associate with Graham – bowls and jugs. “Claret jugs are lovely to make”, he once commented. “You can express a lot with a jug – generosity, a convivial gathering – they are such an expressive thing.”

Certainly when designed by Graham they are. His sweeping the handles to the necks of the jugs and seemingly into the pronounced spouts resulted in the vessels gaining great fluidity, turning a functional object into a work of art.

Graham had a great respect for words and read poetry and attended readings.

He was a devotee of the Irish bard Seamus Heaney. When he discovered that Heaney’s favourite piece of prose was the BBC Radio’s Shipping Forecast, this eventually resulted in a series of bowls that have been much admired.

The Forecast with such names as: East Dogger, Northwest German Bight and Cromarty has an almost hypnotic quality.

Graham engraved his selection on to a circular disc and raised it into a bowl. He chose and arranged the words with the flow of a poet. The series was expanded to other themes.

During the winter of 2003, Graham and three other Scottish silversmiths were invited by the Incorporation of Goldsmiths in Edinburgh (the Incorporation) to compete in a closed competition to design a contemporary version of the Three Honours of Scotland.

Graham’s objective was to get the sword, sceptre and crown “in one flowing whole”. He knew what he wanted, but trying to get there was a lengthy process.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdElizabeth looked at some of his designs and asked, “What’s the message?”

That question acted as a key and eventually a breakthrough was made. Graham won the competition.

Designing the sculpture was one thing, making it was another challenge. It was all hands to the deck at Dunblane – Graham, Iain and two smiths in the workshop.

Vigorous hammer work was required to forge certain components, but a hydraulic press, which Iain constructed, was also needed.

The Queen presented the finished creation to the Scottish Parliament upon the opening of its new building on October 9 2004. All tours of the building start at the sculpture.

It was not long before the Incorporation was commissioning another exciting project of which Graham was part – the Silver of the Stars, which saw ten international Scottish celebrities, from the late actor Sir Sean Connery to thriller author Ian Rankin, paired with ten of Scotland’s finest silversmiths.

Each celebrity had to design a piece of silver on the scenario of a drink with a close friend, and the smith to make the object.

Graham was paired with Alexander McQueen from the world of fashion, who designed a heavy absinthe goblet and spoon, the former bearing the gargoyle-type heads of Punch and Judy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile beautifully crafted by Graham, it was as far from his style as anything could be.

The Silver of the Stars was to travel the world and Graham gently asked Mary Michel, the then Director of the Incorporation, if he could make a piece to accompany it. He designed and crafted a large Mobius Bowl. It was greatly admired by many on its journey from St Petersburg to Kyoto.

After Mary’s brother Thomas died, the family commissioned Graham to make a trophy to be awarded each year in his memory at the Edinburgh Pipe Band Championships.

Mary recalls: “On the day of the championships Graham was there, with his lovely smile. This for me is a snapshot of Graham – a thoughtful and imaginative designer, an incredibly talented silversmith who could encapsulate so much meaning into a single piece; and above all, a gentle man with whom it was always a pleasure to work.”

A selection of Graham Stewart’s work may be viewed on The Gallery of his website: www.grahamstewartsilversmith.co.uk/gallery.php

Graham is survived by his wife Elizabeth, their children Thomas and Hannah and their grandson Ivor.

JOHN ANDREW

Curator, The Pearson Silver Collection