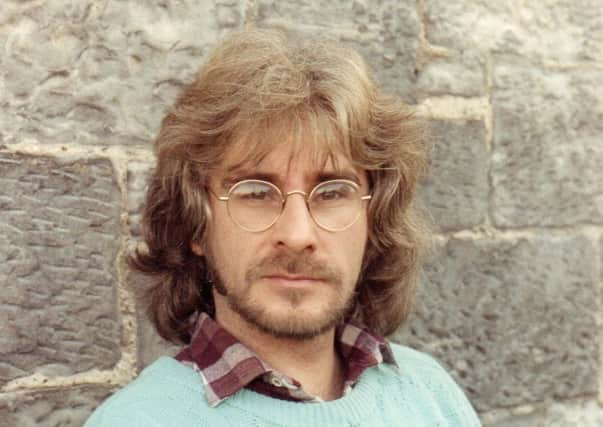

Obituary: Charles Nowosielski, visionary director behind Theatre Alba

In the spring of 2013, Donald Smith, director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh, asked Charles Nowosielski what show he was planning for Theatre Alba’s visit that August to Duddingston Kirk Manse Gardens in Edinburgh. And when he replied, The Diary of Anne Frank, Smith was stunned. “Charlie,” he said, The Diary of Anne Frank is a story about a family taking refuge in a claustrophobic attic. It can’t be done outdoors, it’s impossible!” “Ah,” said Charlie, “but I have an idea…”

And the idea was stunning. He placed the actor playing Anne Frank in a small wooden framework surrounded by barbed wire, knowing that that – along with the wash of music and his lighting growing stronger against the darkening skies – would create an atmosphere of claustrophobia more powerful than any tiny indoor Fringe studio could achieve, simply because it was outdoors. As Smith remarked: “Charlie used unconventional spaces brilliantly, and conventional spaces unconventionally.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCharlie was born in Edinburgh in 1953 to a Polish father, Wlodzimierz (known as Wlodek), and Scottish mother, Grace, and was the youngest of four children. He was educated at St Peter’s RC Primary School and George Heriot’s School, where he captained the school’s 1st XV rugby team.

But it was the playing fields of theatre that had captured Charlie’s imagination and, after leaving Heriot’s, he travelled south to study at the prestigious London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. There, he met one of his long-time friends and theatrical collaborators Jeffrey Daunton, who recalled that Charlie secured his first professional acting job on the day they both graduated in 1975. “A tutor told Charlie to get to Regents Park in London,” said Daunton, “for an audition for A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Open Air Theatre.

But, when he got there, he couldn’t find a gate to get into the park. So he climbed a wall and when he got to the top, he could hear a voice asking “so where’s this Nowosielski fellow…?’ and Charlie, sitting on the wall, very Puck-like, waved and shouted, ‘I’m here, I’m here!’ He was hired on the spot.”

But although he worked as an actor in London and in various theatres in Scotland and abroad in the mid-to-late seventies, Charlie was developing a broader vision of becoming a director and, while he was working at Dundee Rep in the late Seventies, he was asked to direct a series of short plays at the theatre, including Joan Ure’s Something in it for Cordelia. It was a pivotal moment in his career and led him, in 1981, to forming his own company, Theatre Alba, dedicated to new work in the Scots tongue.

“The Eighties was a great time for artists challenging conventional ideas of ‘Scottishness’ in theatre,” said Scotsman theatre critic Joyce McMillan. “At that point, we were often still stuck with the twin stereotypes of White Heather Club Highland nostalgia, or gritty urban decline and violence, which were never representative of Scottish culture as a whole.

But around that time, Charlie and others began experimenting with the whole range of what the Scots language could do, in terms of politics and legend, romance and beauty; and Charlie’s work was very empowering for the artists he worked with, and for everyone in the audience or on stage who was interested in what their Scottish identity meant.”

Theatre Alba’s first production in 1981, Tamlane, was an immediate statement of intent. Edwin Stiven’s play was based on a legendary character in a Scottish Borders ballad, Tam Lin, who was rescued by his true love from the Queen of Elfland. First performed at the Bedlam Theatre in Edinburgh, it had an inauspicious start, playing in front of an audience of four – two critics, one Arts Council representative and, according to Charlie, “a wee old man who had somehow made his way up from the Grassmarket”. But the production burst into magical life when Alba performed it at midnight in Regent Gardens high on Calton Hill in the 1981 Festival Fringe. In the following year, Theatre Alba produced The Shepherd Beguiled by Netta B Reid, another mystical marvel based on Scottish legend, as part of a season of plays at the Astoria in Edinburgh, and both shows went on to enjoy sell-out productions at the Traverse. In the mid-Eighties, his production of David Purves’ The Puddok an’ The Princess earned a Fringe First and went on to tour Scotland.

But it wasn’t just new written work that Charlie used in his exploration of the essence of Scottishness. His vision was total theatre, using music and movement not as a mere accompaniment to the spoken word, but as an integral part of it. In 1981 he was introduced to Richard Cherns, a musician who was about to join the Scottish band Run Rig, shortly before the production of Tamlane in Regent Gardens. Charlie was interested in Cherns’ background in folk music and asked him to write a piece for the play and direct the music. “He took a chance with me,” said Cherns, who hadn’t written music for theatre previously, “and I’m so grateful he did.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was the start of a working partnership and friendship that spanned nearly four decades with Theatre Alba. And when Charlie was appointed Artistic Director at the Brunton Theatre in Musselburgh in 1986, he brought Cherns with him as Musical Director/composer. They worked on dozens of shows there over five seasons – and, at the same time, toured with Theatre Alba – before Charlie became Artistic Director of the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, where he took Cherns in 1991. They also worked together on two productions for the Edinburgh International Festival – Holy Isle by James Bridie in 1988 and The Bruce in 1991.

Cherns added: “What was brilliant about Charlie was his innate capacity to weave together music with words, space, movement and archetypal imagery. He could reach ‘beyond’, evoking a reality that resonates with the depth of human longing and, at the same time, completely connect with the audience.”

Charlie spent two years in Belfast before returning to Scotland in 1993 and creating the MPR Theatre Studio in Musselburgh, where he lived with his wife, the late Scottish actress Anne Lannan, and daughter Ana for some time before moving to Haddington. MPR provided drama classes for children and moved on to form a wing of Theatre Alba for amateur players. In 1998, Charlie took Theatre Alba to its new Festival Fringe home in Duddingston, where they played for the next 20 years, producing a diverse range of work, from The Tempest to The Lass wi’ the Muckle Mou. In 2002 he added children’s shows to the repertoire, producing them with two more long-term theatrical collaborators - actor, writer and director Clunie MacKenzie and actor/musician John Sampson – and, from 2003 until 2018, he produced four quinquennial Passion Plays which were performed on Easter Sundays around almost the entire Duddingston village. And in those 20 years the company gathered a loyal following who appreciated that, in Charlie, they were watching a master of outdoor theatre at work.

In 2010 and 2011 he commissioned his friend, the celebrated Scottish playwright Jo Clifford, to adapt Anton Chekov’s The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard. Clifford said: “He was a very great man of the theatre. It was one of the privileges of my career to have worked with him.

Two replacement hips, a legacy of his early rugby-playing life, made it difficult for Charlie to carry on directing outdoors, but, though time may have slowed him, his vision of theatrical beauty never faded. As McMillan said, on hearing of his death: “Charlie’s contribution to Scottish theatre in the 1980s was huge and just constantly surprising and inventive. Brilliant, beautiful, European, sexy and Scots. He helped change our theatre culture for good, and his work should never be forgotten.”

Charlie is survived by his son Stefan (by his first marriage to Sharon Erskine), Ana (daughter of his late second wife, Anne Lannan), and by sisters Olenka, Barbara and Anna.

JOHN McCOLL

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.