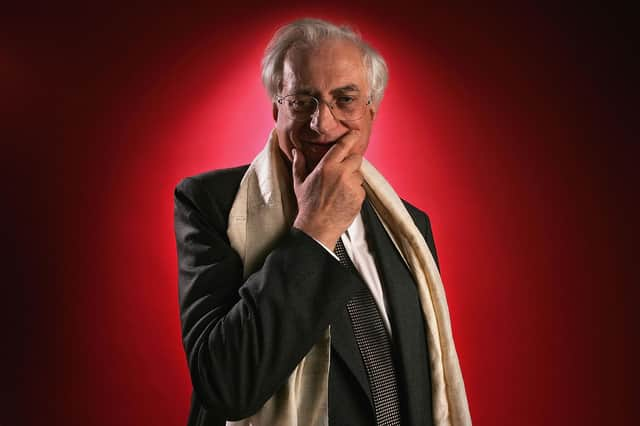

Obituary: Bertrand Tavernier, French director who filmed classic in Glasgow

Bertrand Tavernier was one of France’s most distinguished film makers of recent times, accumulating four Cesars, the French equivalent of Oscars, as either writer or director, and a slew of other accolades.

He reached big international audiences with Round Midnight, his 1986 drama about a black jazz musician in Paris, and the 1989 Bafta-winning drama Life and Nothing But. However, one of his most remarkable films was shot not in France, but in the streets of the Gorbals and around the tombs of the Glasgow Necropolis. Death Watch, in which a terminally ill woman becomes the subject of a voyeuristic reality television show, was way ahead of its time when it appeared in 1980, two decades before Big Brother.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLike Round Midnight, Death Watch was shot in English and despite an impressive international cast, including Harvey Keitel, Harry Dean Stanton and Max von Sydow, it got mixed reviews and then pretty much disappeared before re-emerging on DVD and Blu-ray in 2012. Austrian star Romy Schneider played a woman who agrees for her remaining days to be broadcast on a TV show. She changes her mind and heads off into the countryside with Keitel’s character, but he is secretly working for the television company and recording and transmitting her movements via cameras in his head.

Tavernier had planned to shoot in Berlin before a chance visit to Glasgow prompted a change of mind. “No other city has impressed me so forcefully,” he said, ”a rich 19th-century town, now strangely depopulated.” He filmed in the Necropolis (a memorable opening crane shot) and Finnieston on the Clyde, and contrasted the affluence of the West End with the poverty of the Gorbals. He also filmed on the Kintyre peninsula.

“Glasgow was very much on the cusp between what it was and what it is now,” said Iain Smith, a film producer who worked with Sean Connery on various projects and was location unit manager on Death Watch. “He liked the old Victorian mercantile decadence and loved the gap sites,” Smith told me in an interview in 2000 to coincide with the launch of the first series of Big Brother on Channel 4, at a time when Death Watch was unavailable in any format and had an almost mythical reputation.

There was one awkward moment when Tavernier attended a civic reception and the Lord Provost asked why he chose Glasgow over Edinburgh. “Edimbourg is too beautiful,” the director explained, matter-of-factly. There was a horrible silence. And with perfect timing, Tavernier added: “Glasgow, on the other, hand is dramatic.”

Death Watch is set in the near future and the city is actually unnamed in the film, but it serves as a unique record of Glasgow at a time when virtually no feature films were made there and it was going through huge environmental changes. The film was restored and relaunched at the Glasgow Film Festival in 2012 at an event attended by Tavernier. The Glasgow distribution company Park Circus rereleased it in cinemas and on DVD and Blu-ray and its reputation and audience has grown.

“His Death Watch of 1980 is one of the cult sci-fi movies of the late 20th century – and, fascinatingly, one of the great Glasgow movies, perhaps the greatest,” said Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw.

René Maurice Bertrand Tavernier was born in Lyon in Nazi-occupied France in 1941. His father was the editor of a literary journal. Tavernier survived tuberculosis and during his lengthy recovery he became a passionate film fan. As a student in Paris he began going to the cinema every day, often in the company of his friend Volker Schlöndorff, who also became a distinguished film-maker and directed The Tin Drum. Tavernier wrote film reviews, interviewed the French director Jean-Pierre Melville for an article and wound up going to work for him as an assistant director, though it was not a particularly happy partnership.

Tavernier said later that Melville was a tyrant on set, that he lived in fear of him and that he, Tavernier, was terrible at his job. He was more comfortable as a film publicist, a job he did for several years. He was into his thirties before he co-wrote and directed his first low-budget film, The Watchmaker of St Paul, a thriller based on a Georges Simenon novel, about a widower whose teenage son kills someone and goes on the run with his girlfriend. Shot with a handheld camera in Tavernier’s hometown of Lyon, The Watchmaker of St Paul began a long association with actor Philippe Noiret, it won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 1974 and signalled the arrival of a major new director. Death Watch came just six years later.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTavernier had a particular penchant for thrillers, continuing the obsession of the slightly earlier French New Wave of which Melville had been a part. But his films range across various genres, including period drama, and he even made a Three Musketeers film. His movies are marked by a slow, meditative pace that delighted some and infuriated others. He found an appreciative audience in the UK on the arthouse circuit.

Tavernier made films in both French and English and his best-known works include Sunday in the Country, a painterly film about an artist, and the family drama These Foolish Things, aka Daddy Nostalgie, Dirk Bogarde’s last film.

As well as writing and directing films, Tavernier worked for the preservation and promotion of French film history.

He is survived by his wife Sarah and two children from an earlier marriage that ended in divorce.