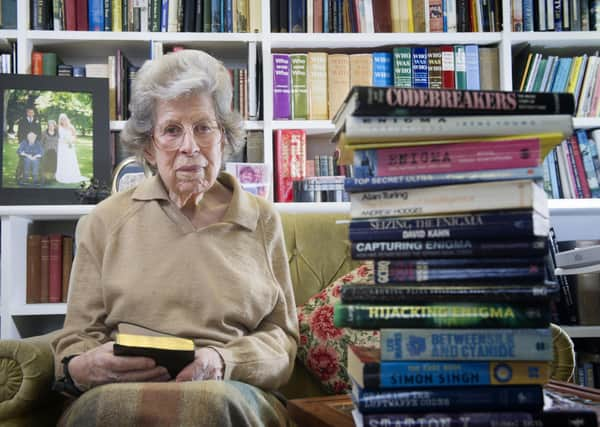

Obituary: Ann Mitchell, Bletchley Park codebreaker, researcher and author

When Ann Mitchell was called up for Second World War service in 1943 in the Foreign Office, she had no idea what kind of job she was accepting. The Oxford mathematics graduate spent the next two years at Bletchley Park, cracking secret messages sent by the Germans. Later in life her pioneering research into the effects of divorce on children helped change Scots law.

Born and brought up in Oxford, Ann’s father had recently left his post as a Commissioner with the Indian Civil Service while her mother, who had been a nurse in a Great War casualty station, helped to run one of Britain’s first family planning clinics.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnn won a scholarship to Headington School for Girls, a short walk from the family home, where she showed an aptitude for maths despite being discouraged: “My headmistress firmly told my parents that mathematics was not a ladylike subject,” she recalled. “She herself taught chemistry, which was surely even less ladylike. However, my parents overruled her and I pursued my chosen path.”

Ann was one of only five women accepted to read maths at Oxford University in 1940. She was also an accomplished swimmer, thanks to daily practice in her school’s unheated outdoor pool, and continued competitive swimming at Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford, representing the university. University in wartime had its privations, particularly in winter as Ann’s room was heated by an open fire but, due to rationing, there was only enough coal for one day and one evening a week.

Ann played her part in the war effort, Digging for Victory by growing vegetables on the college lawn; serving at canteens for servicemen; and collecting scrap to meet the wartime shortage of metal.

After a focused degree course that took three years instead of the usual four, she graduated in mathematics from Oxford in 1943 and knew she would be called up for some kind of war service. To her relief, the University Appointments Board sent her to a place called Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, to become a temporary assistant in the Foreign Office. She soon found it was the headquarters of the Government Code and Cypher School, with the war-time title of Station X.

Ann was assigned to one of the many single-storey buildings in the grounds of Bletchley Park, where she was initiated into the secret world of codebreaking. She remained until the end of the war in the Hut 6 Machine Room, so called because it had a number of British-made enciphering machines that were similar to German Enigma machines.

The Machine Room was connected to the Watch, the vital hub around which the whole hut worked on deciphering coded Enigma messages which had been intercepted.

At listening posts all over Britain, wireless operators had to concentrate intently for hours on end in order to write down meaningless strings of letters in Morse and these messages were then transmitted to Bletchley Park. Hut 6 dealt with the high priority German army and air force codes, most important of which was the “Red” code of the Luftwaffe.

They wrote out some of the jumbled nonsense which had been received and underneath wrote a “crib” of the probable German text. Ann’s key role was the next step in breaking the code, composing a menu that showed links between the letters in the text received and the crib, with the more compact the menu, the better. As every code for every unit of the German forces was changed at midnight, each day the work began all over again to identify clues to the new day’s codes. It was an intense intellectual process, working against the clock, and the urgency provided a constant challenge. Ann and her colleagues in Hut 6, most of whom had degrees in economics, law or maths, worked around the clock in shifts, with one free day each week. As the war came to a close, the number of messages declined until there were no more. “I did go up to London for VE Day on 8 May 1945 but I remember very little about the celebrations,” she said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe codebreakers returned to normal life and, having signed the Official Secrets Act and sworn not to divulge any information about her work, Ann never told anyone, not even her husband, about her wartime role. She was therefore amazed, in the 1970s, to find that books were being published about Enigma. Once the secret was out she was delighted that she could talk about her life during wartime, and gave illustrated talks around the country.

Requests from media outlets came on a regular basis as new films and books about Bletchley were published, and she was interviewed well into her nineties, most recently for Tessa Dunlop’s The Bletchley Girls. She said: “It was a fillip towards the end of my life, suddenly to have risen in importance, to go from being a nobody to a somebody. A whole past that nobody was interested in and suddenly lots of people are. It’s very strange.”

It has been said that the work of the Enigma codebreakers shortened the war by two years but their achievements were not formally recognised until 2009, when Ann and other surviving Bletchley veterans were awarded a commemorative badge by GCHQ. “I am proud of what we did,” she said. “It is just a small badge, but it means a lot to me.”

After the war she worked as a secretary before meeting her future husband Angus, who had been decorated on active service with the Royal Armoured Corps and was by then a student. After he graduated from Oxford in 1948 they married and the young couple moved to Edinburgh, where Angus embarked on a career with the Scottish Office, rising to become Secretary of the Scottish Education Department. In 1953 they bought a townhouse in Regent Terrace, where they would spend over 50 years, and proceeded to fill it with their growing family.

Ann was keen on social issues and trained as a volunteer counsellor for the Edinburgh Marriage Guidance Council. In time, she noticed that the focus of failing marriages was almost entirely on the parents, while children were left to muddle through. She decided to research the effects of divorce on children.

Her groundbreaking efforts led not only to an MPhil from Edinburgh University, they prompted changes to Scottish law which ensured that the needs of children were properly taken into account in a divorce settlement. Her first book, Someone to Turn To, Experiences of Help before Divorce (1981), examined where recently divorced people had sought or received help when their marriages had broken up, exposing substantial dissatisfaction with Scottish legal procedures.

She was particularly concerned that the needs and feelings of children were often ignored, and her seminal work Children in the Middle (1985) gave considerable impetus to the use of mediation in family cases. Her writing took a new tack with two acclaimed local history books on Edinburgh, The People of Calton Hill (1993) and No More Corncraiks (1998). At the age of 89 Ann published a biography of her mother, Winifred.

In 2015, with failing eyesight and limited mobility, she and her husband moved together to St Margaret’s Care Home. Angus died in 2018 and she is survived by their four children Jonathan, Charlotte, Catherine and Andy, and six grandchildren.

ANDY MITCHELL

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.