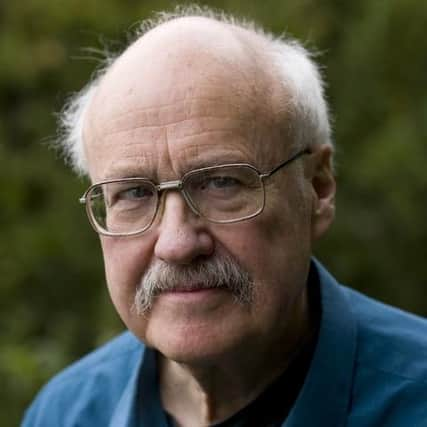

Obituaries: Lyell Cresswell, New Zealand-born composer who made home in Scotland

Back in the 1980s, the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra performed a new work by Lyell Cresswell. Older members of the orchestra still remember with fondness the New Zealand-born composer seated quietly among the audience wearing a T-shirt that identified its wearer as a “living composer”. It was a silent protest against orchestras’ tendencies to favour the music of dead composers.

For Cresswell, who lived most of his highly productive life in Edinburgh, but maintained a regular professional presence in his native New Zealand, such muted eccentricity was perfectly in tune with his ambivalent personality and charm. On the outside, he was quietly spoken with a tendency to speak tersely and hurriedly, punctuated by an infectious giggle. Inwardly, he was a creative heavyweight, his music channelling the real Lyell: original, quirky, humorous, honest and, where necessary, ferociously caustic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2016, having received a prestigious Arts Foundation Laureate, he was asked on New Zealand Radio what motivated him as a composer. He responded: “What I’m doing is writing my own biography. If I were doing it with words, I’d just be telling a pack of lies, but when I’m writing music I find it’s impossible to tell lies. I’m telling my story, my view of the world, in terms of feelings and emotions.”

That admission chimes with Edinburgh author and poet Ron Butlin, whose close friendship with the composer extended to creative collaborations, including two short opera projects for Scottish Opera. “He did actually write about this life in a private memoir”, recalls Butlin. “He told me he made a lot of it up. I was no wiser as to what was actually true, but it was a great read.”

As a composer, though, everything Cresswell produced was pointedly genuine. His output was immense, covering all genres from solo voice and chamber ensemble to large-scale orchestra, choral and opera, emanating from a musical voice that was probing, proficient, relevant and fiercely original. “He was an adventurer”, says fellow composer and author of Scotland’s Music, John Purser.

Those who shared that adventure benefited greatly from it. As an undergraduate at Edinburgh University in the 1970s, the young Sir James MacMillan fell under Cresswell’s spell, especially his early orchestral work Salm, a vivid exploration of the beguiling heterophonic techniques of Gaelic psalm singing which had won Cresswell the Ian Whyte Award. “It had a huge impact on me”, recalls MacMillan, whose adoption of the same techniques were key in shaping his own musical fingerprint.

Lyell Cresswell was born in Wellington, New Zealand, in 1944 to Jack, an accountant, and Muriel (née Sharp). Both parents were committed members of the Salvation Army, through which the young Lyell – learning the trumpet – experienced music from a young age. He had two older brothers, Roger and Max, the latter a leading philosopher and academic who survives him.

After graduating from Rongotai Boys’ College, Cresswell attended Victoria University in Wellington, studying composition with Douglas Lilburn (a pupil of Ralph Vaughan Williams). There, he met and fell in love with fellow music student Catherine Mawson, a cellist. They wed in 1972.

That same year, the newlyweds moved to Aberdeen where Cresswell had secured a scholarship to pursue a PhD in composition. He became close friends with fellow student Michael Tumelty, former music critic of the Herald, whose later recollection of Cresswell’s music offers an early insight into the power and density in his orchestral scores. “They looked like landscapes in sound, with great slab-like formations of notes, sometimes monolithic, sometimes imperceptibly slow-moving,” wrote Tumelty in 2001.

Cresswell went on to study in Utrecht, then a hotbed of contemporary music, moving to Cardiff in 1978 where he ran the city’s Chapter Arts Centre. Scotland lured him back, as Edinburgh University’s Forman Fellow in Composition from 1980-82, then to Glasgow University as Cramb Fellow in Composition from 1982-85. Thereafter, now settled in Edinburgh, and clear in his mind that teaching was not his preferred option, Cresswell set out on a path dedicated wholly to composition.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was the right decision. The commissions kept coming, both from Scotland and New Zealand, which enabled him and Catherine to make regular visits home. The Royal Scottish National Orchestra, which had performed the award-winning Salm, showcased Cresswell as a featured composer in the 1984 Musica Nova Festival in Glasgow. As artistic director of the Edinburgh Contemporary Arts Trust, he further established his own name, but equally he promoted works by others who intrigued him, including fellow composers from New Zealand who featured in two ECAT New Music NZ Festivals.

A close association with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra resulted in some of his most audacious works, from the epic Shadows Without Sun, for which he drew on his own experiences in (albeit self-imposed) exile, and his concerto for chamber orchestra, Of Smoke and Bickering Flame, to the completion of a movement from the unfinished Symphony No 3 by Edward Harper, a close friend who had just died.

If his operatic prowess was never fully exploited, the two short works he and librettist Ron Butlin produced in response to Scottish Opera’s Five-15 project – The Perfect Woman (2008) and The Money Man (2010) – were highly acclaimed successes. “Scottish Opera’s original intention was to stage an extended version of The Money Man, but ironically funding issues put paid to that,” recalls Butlin. “It was all written, but it’s never been performed.”

Cresswell’s music has been lauded worldwide, from performances at the Warsaw Autumn, BBC Proms and Edinburgh International Festival, to Tokyo, Bologna and New Zealand. Among numerous awards were recommendations by the Unesco International Rostrum of Composers, an honorary doctorate from Victoria University in Wellington, the inaugural Elgar Bursary and the Sounz Contemporary Award for his Piano Concerto.

Cresswell died in March from liver cancer, complicated by Covid. He is survived by his wife Catherine.

Obituaries

If you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), or have a suggestion for a subject, contact [email protected]

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription. Click on this link for more details.