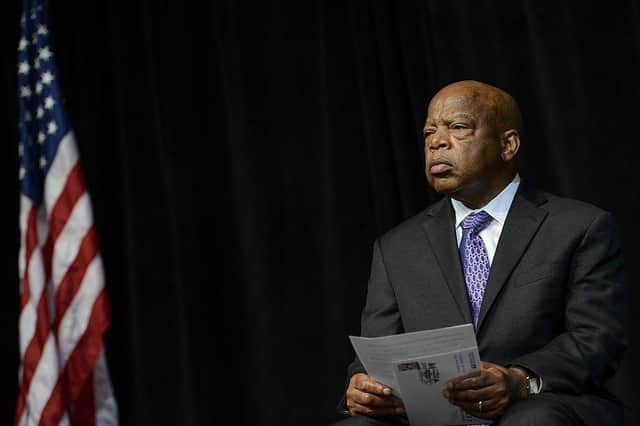

John Lewis, lifelong civil rights activist and US congressman

People paid great heed to John Lewis for much of his life in the civil rights movement. But at the very beginning – when he was just a boy wanting to be a minister someday - his audience didn’t care much for what he had to say.

A son of Alabama tenant farmers, the young Lewis first preached moral righteousness... to his family’s chickens.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLewis was the youngest and last survivor of the Big Six civil rights activists who organised the 1963 March on Washington, and spoke shortly before the group’s leader, the Rev Martin Luther King Jr, gave his “I Have a Dream” speech to a vast sea of people.

If that speech marked a turning point in the civil rights era – or at least the most famous moment – the struggle was far from over. Two more hard years passed before truncheon-wielding state troopers beat Lewis bloody and fractured his skull as he led 600 protesters over Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Searing TV images of that brutality helped to galvanise national opposition to racial oppression and embolden leaders in Washington to pass the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act five months later.

“The American public had already seen so much of this sort of thing, countless images of beatings and dogs and cursing and hoses,” Lewis wrote in his memoirs. “But something about that day in Selma touched a nerve deeper than anything that had come before.” That bridge became a touchstone in Lewis’ life. He returned there often during his decades in Congress representing the Atlanta area, bringing politicians from both parties to see where “Bloody Sunday” occurred.

More brutality would loom in his life’s last chapter. He wept watching the video of George Floyd’s death at the hands of police in Minnesota. “I kept saying to myself: How many more? How many young Black men will be murdered?” he said last month.

Yet he dared to hope: “We’re one people, we’re one family. We all live in the same house, not just the American house but the world house.”

Lewis earned bipartisan respect in Washington, where some called him the “conscience of Congress”. His humble manner contrasted with the puffed chests on Capitol Hill. But as a liberal on the losing side of many issues, he lacked the influence he’d summoned at the segregated lunch counters of his youth, or later, within the Democratic Party, as a steadfast voice for the poor and disenfranchised.

He was a guiding voice for a young Illinois senator who became the first Black president. “I told him that I stood on his shoulders,” Barack Obama wrote in a statement marking Lewis’s death. “When I was elected President of the United States, I hugged him on the inauguration stand before I was sworn in and told him I was only there because of the sacrifices he made.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLewis was a 23-year-old firebrand, a founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, when he joined King and four other civil rights leaders at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York to plan the Washington demonstration. The others were Whitney Young of the National Urban League; A. Philip Randolph of the Negro American Labor Council; James L. Farmer Jr, of the interracial Congress of Racial Equality; and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP.

At the National Mall months later, he had a speaking slot before King. He vowed: “By the forces of our demands, our determination and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in an image of God and democracy.” His words were soon and for all time overshadowed by the speech of King. “He changed us forever,” Lewis said of King’s oratory that day.

But the change the movement sought would take many more sacrifices.

After months of training in non-violent protest, demonstrators led by Lewis and the Rev Hosea Williams began a march of more than 50 miles from Selma to Alabama’s capital in Montgomery. They didn’t get far: on 7 March 1965, a phalanx of police blocked their exit from the Selma bridge. Authorities swung truncheons, fired tear gas and charged on horseback, sending many to the hospital. The nation was horrified.

“This was a face-off in the most vivid terms between a dignified, composed, completely non-violent multitude of silent protesters and the truly malevolent force of a heavily armed, hateful battalion of troopers,” Lewis wrote. “The sight of them rolling over us like human tanks was something that had never been seen before. People just couldn’t believe this was happening, not in America.”

King swiftly returned to the scene with a multitude, and the march to Montgomery was made whole before the end of the month.

Lewis was born outside Troy, in Alabama’s Pike County. He attended segregated public schools and was denied a library card because of his race, but he read books and newspapers avidly, and could rattle off obscure historical facts even in his later years.

He was a teenager when he first heard King, then a young minister from Atlanta, preach on the radio. They met after Lewis wrote to him seeking support to become the first Black student at his local college. He ultimately attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary and Fisk University instead, in Nashville, Tennessee.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSoon, the young man King nicknamed “the boy from Troy” was organising sit-ins at whites-only lunch counters and volunteering as a Freedom Rider, enduring beatings and arrests while challenging segregation around the South. Lewis helped form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to organise this effort, led the group from 1963 to 1966 and kept pursuing civil rights work and voter registration drives for years thereafter.

President Jimmy Carter appointed Lewis to lead Action, a federal volunteer agency, in 1977. In 1981, he was elected to the Atlanta City Council, and then won a seat in Congress in 1986.

Humble and unfailingly friendly, Lewis was revered on Capitol Hill. When Democrats controlled the House, he tried to keep them unified as his party’s senior deputy whip. The opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture was a key victory. But as one of the most liberal members of Congress, spending much of his career in the minority, he often lost policy battles, from his effort to stop the Iraq War to his defence of young immigrants.

Lewis also met bipartisan success in Congress in 2006 when he led efforts to renew the Voting Rights Act, but the Supreme Court invalidated much of the law in 2013, and it became once again what it was in his youth, a work in progress.

Lewis said he had been arrested 40 times in the 1960s, five more as a congressman. At 78, he told a rally he would do it again to help reunite immigrant families separated by the Trump administration.

“There cannot be any peace in America until these young children are returned to their parents and set all of our people free,” Lewis said.

Lewis announced in late December 2019 that he had been diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer. “I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now,” he said.

Lewis’ wife of four decades, Lillian Miles, died in 2012. They had one son, John Miles Lewis.

CALVIN WOODWARD

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.