International Women's Day 2021: The secret history of some of Scotland's most extraordinary women

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

To mark International Women’s Day, we have delved into untold stories of women in Scottish history.

History is told by the victors, we often hear. And the victors have – more often than not – been white men. Beneath the well-known stories of Robert the Bruce, William Wallace, and Robert Burns, hidden stories have been unearthed in recent years which tell a different side of our nation’s history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese are the stories of women who were enslaved. Women who fought back against oppression, against societal norms and conventions.

Women who were sexual rebels and revolutionaries and campaigned radically for what they believed in.

With the help of Scottish historians, we’ve discovered some extraordinary women who led extraordinary lives, from 500 years ago up to the turn of the 20th Century.

The first black women in Scotland?

Though it was believed African people first arrived in Scotland in the 18th century, there is evidence they were here much earlier.

Two enslaved African women were welcomed to the heart of the royal court in the 16th century.

The pair caused a sensation on their arrival to Edinburgh in 1506, says Dr Christine Whyte, a lecturer in global history at the University of Glasgow.

They had been seized from a Portuguese ship by the Barton brothers – sailors from Leith – and were presented as a ‘gift’ to King James IV.

According to records from the time, the king was pleased and gave the Barton brothers the right to seize more Portuguese ships and their ‘goods’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKing James “not only accepted the gift but took the greatest interest in their welfare” and welcomed the pair into the Queen’s household.

They joined the Scottish king’s court, were baptised, and renamed ‘Blak’ Helen (or Ellen) and ‘Blak’ Margaret. Their real names and the country they were taken from are sadly not known.

Helen became a lady-in-waiting to Queen Margaret and was described as the “Quenis blak madin”. She was awarded a position given to the most beautiful woman in the court – the lady of ‘the tournament of the black knight’,

Helen was adorned in lavish clothing for the grand occasion, and she was immortalised by it, as well as a poem about her written by William Dunbar.

Dr Whyte and many others view ‘Of Ane Blak-Moir’ as a racist poem, due to its mocking language about Helen’s appearance.

Jennifer Melville, of the National Trust’s Facing Our Past initiative, writes: “The poem now serves as not only a window into a bygone courtly life but also as a sad indictment of Scottish perceptions to race revealed in what is possibly the first poem of this type to be written about an African woman in the English language.”

Helen and Margaret are thought to be the earliest recorded black women in Scotland.

Dr June Evans of African Women in Scotland writes: “Looking at it from a gender perspective, the position of these two women was extraordinary for they were in positions that were the reserve of the aristocracy. The two African women were within the inner circle."

Slavery and resistance

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut many black women had it much harder in Scotland. During the time of the transatlantic slave trade, African women were forcibly brought to Scotland as slaves and traded here – but many resisted.

Dr Whyte points out an advert in the Edinburgh Evening Courant, dated 1777. It documents the seventh time a black 18-year-old woman named Ann had run away from a Dr Gustavus Brown’s lodgings in Glasgow.

She was wearing a “green gown and a brass collar about her neck” with Dr Brown’s name engraved onto it.

"Whoever apprehends her, so as she may be recovered, shall have two guineas reward," the advert says, “and necessary charges allowed by Laurance Dinwiddie Junior Merchant in Glasgow, or by James Mitchelson, Jeweller in Edinburgh.”

Another woman, named Peggy, was advertised as for sale in the Courant on 30 August 1766. The newspaper describes her as ‘to be disposed of’. She was 19-years-old and grew up in Charleston, South Carolina. She was an “exceedingly good house wench,” the advert says, and had a young child, about one-years-old, to be “disposed of” with her.

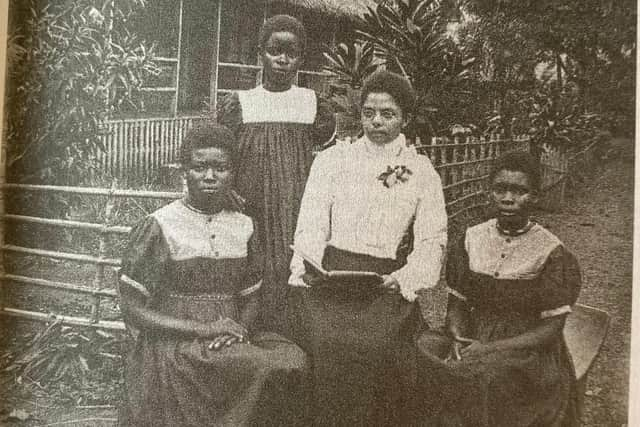

Then there is Lena Clark, whowas an African woman from the Congo area, who was ‘adopted’ by a missionary and brought to Scotland between 1889 and 1891.

She then went to college in the US and in 1895 returned to the Congo. Eight years later Lena assisted the famous Irish reformer Roger Casement to interview people about the atrocities committed in the Belgian Free State.

"She was a very talented linguist. and translated the interviewees testimonies,” said Dr Whyte, “She didn’t spend too long in Scotland, but I think it is an interesting and significant story.”

The sensational murder trial of Madeleine Smith

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Men still tend to dominate in popular narratives of Scottish history – Wallace and Burns, the lad o'pairts and the hard man,” says Dr Tanya Cheadle, a lecturer in gender history at the University of Glasgow.

"Happily however, women's and gender historians – both at Glasgow's Centre for Gender History and elsewhere – have been writing and teaching more inclusive histories of Scotland for the last three decades, and I know schools are doing good work here too.”

Dr Cheadle draws attention to the somewhat scandalous life of Madeleine Smith, accused of poisoning her lover with arsenic-laced cocoa.

The Glaswegian middle-class daughter of an architect, in the 1850s Madeleine had an illicit, pre-marital affair with Emile L’Angelier, an upper working-class clerk from the Channel Islands.

L’Angelier threatened to expose their affair by showing her letters – which made explicit her enjoyment of their sexual relationship – to her father.

Dr Cheadle says: “After a reconciliation at Madeleine's bedroom window in Blythswood Square, where she gave him cocoa, Emile died of arsenic poisoning.

"Her murder trial in 1857, which resulted in a verdict of not-proven, was a sensation across Europe, in large part because of the contents of her letters.

"What's fascinating is that, despite strict codes of respectability, Madeleine went on to live a full life, mixing with radical circles in London, marrying, having children and moving to the US.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen there’s the orphaned Scottish-Indian schoolgirl who accused her two school mistresses of having a lesbian affair.

New research by Frances B. Singh has unearthed the story of Jane Cumming, who said her teachers had had sex.

A libel trial unfolded in 1811-1812, where there was general disbelief that two Scottish women could possibly do such a thing.

Lord Woodhouselee is reported as saying: “Such unnatural commerce...in this part of the world...a thing unheard of, a thing perhaps impossible.”

Dr Cheadle said: “In both this trial and that of Madeleine Smith, the reputation of the women accused – and by default of the Scots nation – was preserved by displacing the erotic onto racial 'others'.

"In 1811-12 it was Jane Cumming, in Madeleine's trial it was Emile, who the Glasgow Herald declared dangerously French.”

Pioneers of their time

The fascinating lives of Scottish women who were “sexual rebels” in the conservative Victorian period are explored in Dr Cheadle’s book, Sexual Progressives: Reimagining Intimacy in Scotland.

Jane Hume Clapperton was anearly birth control campaigner, feminist and socialist from Edinburgh who advocated for women’s sexual pleasure. “A radical view for the 1890s,” says Dr Cheadle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen there is Glaswegian socialist and suffragette Bella Pearce, who was the pioneering editor of a feminist newspaper column called ‘Matrons and Maidens’ in the Labour Leader for four years.

Along with her husband Charles, she was also a loyal disciple of a cult leader who taught that religion needed to be ‘re-sexed’.

These are just a handful of women’s lives which have been overlooked in Scottish history until very recently. Spotlighting them now challenges our assumptions of the way things were and give us a more diverse, fuller picture of our nation’s story.

Further reading

- Murder and Morality in Victorian Britain: The Story of Madeleine Smith by Eleanor Gordon & Gwyneth Nair

- Scandal and Survival in Nineteenth-Century Scotland: The Life of Jane Cumming by Frances B. Singh

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.