Insight: Unravelling one of the great miscarriages of justice in Scots law

“Armed with Innocency, I Appeal to Justice…”

Thomas Muir was a Scottish advocate in the late 18th century. In 1793, the ideals of the recent French Revolution were still in the air and the landed classes were peering anxiously over their shoulders.

Everywhere, societies were springing up demanding reform, especially voting reform. If you didn’t own land, you had no right to vote. This had to change.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEnter, Thomas Muir, advocate. Thomas Muir, who counselled peaceful and lawful reform. But to some, it sounded like a call to sedition, an incitement to rebellion.

Passionate, eloquent and charismatic, the young advocate possessed dangerous qualities in a nervous time. Even more dangerous when rioting in Edinburgh landed outside the front door of the Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas.

And so, Thomas Muir, advocate, became a marked man. Lord Advocate Dundas ordered investigation of Muir’s every move and wrote that he would “lay him by the heels on a charge of High Treason”.

When the arrest took place on 2 January 1793, Thomas Muir, ironically, was on his way to represent the accused in a sedition trial. Now Muir was himself arrested for sedition. Bail was granted pending trial.

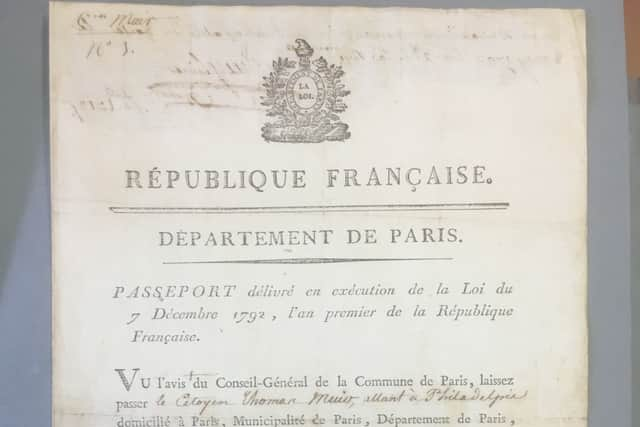

The terms of his bail didn’t restrict Muir from foreign travel, so on 20 January, he travelled to France to use his influence to try to halt the execution of the deposed French king, Louis XVI. Too late. The king was guillotined the day after Muir’s arrival.

Meanwhile, in Scotland, on 26 January, within a week of Muir arriving in France, the Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas issued an indictment against Muir. And Dundas brought forward the date of the trial originally scheduled for the April. It would now be on 11 February – 16 days away. Muir was in France and knew nothing about it.

And then something happened that made Muir’s return home impossible: on 1 February, 1793, France declared war on Britain. All travel between France and Britain was banned. There was now a naval blockade between the countries. Muir was stranded in Paris, an enemy alien in the time of war.

A week later, Muir received communication from his father in Scotland: the trial had been brought forward to 11 February. Muir, now trapped in wartime France, got the letter three days before the trial was due to start in Edinburgh. In the event, the case was continued for two weeks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn 13 February, Muir wrote an open letter to the Edinburgh Gazetteer in Scotland explaining his position: “Armed with innocency, I appeal to justice…”

And then, on the continued trial date of 26 February, the case came before the notorious judge, Lord Justice-Clerk, Lord Braxfield.

Robert McQueen, titled Lord Braxfield, was a figure whose name has come to be associated with the prejudices of the period – and abuses of the law. Famously, he said to one accused: “Ye’re a verra clever chiel’, man, but ye wad be nane the waur o’a hanging.”

On another occasion, when being addressed on the subject of reform, it was submitted that even Christ was a reformer in his times. Braxfield replied: “Muckle he made o’ that: he was hanget.”

In 2006, Scotland on Sunday polled Scottish academics, and Braxfield was named as one of Scotland’s “vilest villains”.

And it was Braxfield who presided over Thomas Muir’s case on 26 February, 1793. Muir was still stranded in France. And it was on that date that Braxfield issued a decree of fugitation – declaring Thomas Muir, advocate, a fugitive from Scottish justice. Muir had now been declared an outlaw.

Three days later, on 1 March, the Edinburgh Gazetteer published Muir’s letter of 13 February with his account of why it was impossible for him to reach Scotland in time for his trial.

Despite the wide publication of Muir’s letter, five days later the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, Henry Erskine, convened a meeting at the Faculty. Muir was not represented. At that meeting, on 6 March, 1793, Thomas Muir was struck off the Roll of Advocates.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen Muir finally made it back to Scotland to face proceedings, the trial that took place, conducted by his avowed enemy, Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas and dominated by Lord Braxfield, is widely acknowledged as one of the great miscarriages of justice in Scots law. Inevitably, Muir was convicted and sentenced to 14 years’ transportation to Botany Bay

2015: ‘The play’s the thing...’

Fast forward 222 years. I had been a Scottish advocate for over two decades and was now working – like Muir, still in wig and gown – as an advocate depute, prosecuting serious crime in Scotland.

I received a call from the then-Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, James Wolffe QC: the Faculty of Advocates was going to hold a celebration of the 250th anniversary of the birth of Thomas Muir. Would I like to write a play for the event? A dramatic reconstruction of the infamous trial? (I had experience of writing for the theatre, having had plays performed in Edinburgh, London and New York). I said yes and asked when the event was.

“It’s in four weeks…”

There were 40 witnesses in the Muir trial. Given the imminence of the event, I needed help to plough through this. The Dean appointed three other advocates, Patricia Comiskey, Iain Smith and Clare Connelly to write me a very short précis of what each witness said. That way, I could get a sense who was relevant and who was not. I started to craft the dialogue. But I didn’t have to look far for the drama. Sometimes the reported exchanges between Muir and the prosecutor Dundas were so vivid, they seemed to jump off the printed page.

The script was finished. But what about a cast? Who was going to speak the impassioned words of Muir? And who could do justice to Braxfield?

The Dean of Faculty had agreed that the Faculty of Advocates would fund some professional actors if need be. But I had a different idea: I was working as a prosecutor. I was surrounded daily by other, expert criminal lawyers. Rather than casting actors to play lawyers, why not enlist the criminal lawyers themselves to play the various parts? Wouldn’t that bring a sense of authenticity to the proceedings? We could just wear ordinary suits and give the trial a contemporary feel. And we could dispense with the 18th century horse-hair wigs.

And so, one-by-one, I put together my “cast”.

I went into the Senior Advocate Deputes’ room. Iain McSporran, Senior Advocate Depute, was engrossed in the papers for the murder trial before him.

Me: Iain, can you do me a favour?

Iain: (Still looking at his papers) Uh, huh?

Me: The Faculty of Advocates is putting on a show in a couple of weeks – The Trial of Thomas Muir. Could you do me a favour and play the part of the prosecutor, Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas?

Iain thought for a moment, then:

Iain: Do I have to wear a wig?

Me: No.

Iain: OK, I’ll do it.

And he went back to his papers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd that’s how the cast was assembled. Prosecution lawyers, defence lawyers – it didn’t matter. Whoever I asked, they all knew the story and there was an overwhelming desire to take part in the re-enactment of Thomas Muir’s case. But who to get for Braxfield?

25 August 2015. The day of the event

Fully cast now, the “actors”, would read from their rehearsed scripts.

The venue: First Division Courtroom, Parliament House, Edinburgh – one of the historic courts in Edinburgh where Muir was declared a fugitive from justice. The court was jam-packed. Hundreds of seats filled in the public gallery. Dozens of requests on stand-by. Even 15 people were crammed into the jury box, as if they were the jurors at a real trial.

The Dean, James Wolffe QC introduced the event and spoke about the lessons to be learned from Muir’s treatment and the right to a fair trial whatever the public climate. Professor Sir Tom Devine, effortlessly erudite, gave a riveting talk outlining the trial its historical context, joking: “The only thing that disappointed me … was that I was not invited to play Braxfield.”

I looked around me and realised that, in casting the trial of Thomas Muir, I had assembled the finest criminal lawyers of our generation: Iain McSporran as the Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas, Alex Prentice QC as a juror, Gordon Jackson QC as a Crown witness, and, up high on that judicial bench, magnificently acting the curmudgeon, Donald Findlay QC as Lord Justice-Clerk, Lord Braxfield (with the real, modern-day Lord Justice-Clerk, Lord Carloway, watching from the front row of the audience).

I stood up and started the play: “It must have been very much like this. And very much like it is today, with the usual people in their usual places. The judges, the lawyers – and the accused…”

The night was a greater success than I could have imagined. The “actors” themselves transformed into their characters, bringing a lifetime of court experience to their roles. At times, I could hear sharp intakes of breath from the audience as the embodiments of prosecutor Dundas and judge Braxfield relentlessly, and unfairly, secured the conviction of Thomas Muir.

2020 ‘Turn every page’

But for me, it didn’t end there. It haunted me. Why hadn’t Thomas Muir been pardoned by now? After all, it had been more than 200 years since Muir’s “show trial”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd the Faculty of Advocates – of which I had been a member for more than two decades – why did they persist in keeping Muir struck off the Roll, when it was obvious that it had been impossible for him to leave France and attend at the Scottish court?

When I made subtle inquiries, the answer came back: at the time the Faculty expelled Muir on 6 March, 1793, it was on the basis that the Court had, in the course of competent proceedings, declared Muir a fugitive from the law. It wouldn’t be right for us in the 21st century to judge the conduct of those in the 18th, since they were acting in accordance with the law as it stood at that time.

I saw the point. But surely, if I could somehow get rid of Braxfield’s fugitation order of 26 February, 1793, then I could ask the Faculty to re-admit Muir, because that court order was the only reason for Muir’s expulsion. It was probably an impossibility now, more than 200 years later, but…

I took a number of different tacks:

(1) if it was, indeed, virtually impossible for Muir (now an enemy alien) to obtain a passport to get out of wartime, post-Revolutionary France, then how could anyone expect him to get back to Scotland to face trial at such short notice? Could this be an inroad into the challenge to the court order: that the order to appear in court that day was impossible to carry out in the circumstances?

So I emailed the world’s leading experts on the history of the passport, explaining my mission. All of them were intrigued and responded, but there was no clear answer. (Perhaps humorously, Professor John Torpey, author of The Invention of the Passport, suggested to me that it would have been easier for Muir to obtain a passport as an enemy alien because France would be keen to chase him out of the country).

Time to try a different tack.

(2) Track down and examine the original court papers of Muir’s trial etc. Could anything there help? Faculty of Advocates librarian, Alistair Johnson located and called up the documents, kept at West Register House in Edinburgh. And when I went into those grand rooms, there were boxes and boxes of documents. Not just the court papers, but random, everyday items, like the contents of Thomas Muir’s pocketbook.

There were various other, more formal, legal documents: the indictment containing the charges of sedition, the witness list and many of these were peppered with passages of Latin (No real problem. I silently thanked my old Classics teachers, Cathie McCormack for her gentle encouragement, and Mr Dourish for his tawse).

The great American biographer, Robert A Caro, said that if you want to know the truth about a situation and are faced with mountains of paper, then you have to “turn every page”. And that’s what I was doing now.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

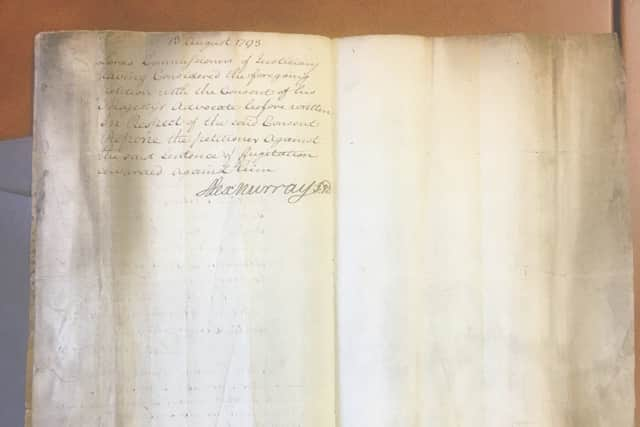

Hide AdPage after yellowing page. Box after box. And then I came across something. A different kind of legal document. It looked like a note of appeal – a “Reponing Note”. If someone has been convicted, and the Court, on appeal, “repones”, then it’s as if the conviction never happened.

And the document before me now – buried among these boxes and papers – was a petition that would be lodged to argue the appeal against Muir’s conviction for fugitation/outlawry. The conviction that had been pronounced by Braxfield. The conviction that was used to expel Muir from the Faculty of Advocates.

I sat back in my chair. If I could show that Muir’s conviction for outlawry had been “reponed” by the Court, then, as a matter of law, it would be as if that conviction had never happened. And if that conviction never happened, then the Faculty of Advocates would have had no valid reason to expel Muir on 6 March, 1793. If there was no valid reason for Muir’s expulsion, then I could ask that Muir be re-admitted to the Faculty.

So, I dug deeper into the boxes of papers, turning every page. Found it. The Reponing Note had been lodged in Court. A good first step. But no guarantee that any appeal would be granted. After all, it would have to have been served on Muir’s sworn enemy – the Lord Advocate, Robert Dundas. And how likely was it that Dundas would have consented to such an appeal being granted? That was just too much to hope for.

I kept churning through the boxes and boxes of papers. And then I found something that astonished me: it was the response of Robert Dundas, Lord Advocate to Muir’s appeal. The Lord Advocate had no objection to the appeal – and that consent was signed by Robert Dundas himself.

Of course, this did not mean that the appeal would be granted automatically. It would need to be considered by the judges of the Court of Session first, and, at the time of the appeal application, Muir was still overseas, on the face of it defying the requirement to return to Scotland for trial.

So, here I was, sitting in West Register House in Edinburgh, thinking: How likely is it that Muir’s appeal against fugitation has been successful, but that it has been buried among these papers for over 200 years?

But, suddenly, there it was. The Court of Session court order dated 13 August, 1793. And it read: “Lords Commissioners of Justiciary having Considered the foregoing Petition with the Consent of his Majesty’s Advocate … Repone the petitioner against the said sentence of fugitation awarded against him.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe appeal against fugitation had been heard. It had been successful. It was as if the conviction for fugitation had never happened.

In the five years since that night when the play was performed, the Great Wheel of Law had turned: the Dean of Faculty, James Wolffe QC had now become Lord Advocate; Paul Brown, who had played Muir, was now a Summary Sheriff; Anna Poole, who played a scurrilous scullery maid on the night, was now a Senator of the College of Justice. And Crown witness Gordon Jackson was now Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, and almost at the point of standing down as Dean.

Covid-19 made communication difficult, but I made a written email motion to have Muir re-instated, and I submitted the evidence. And the reply came:

“Dear Ross

I have examined your written submissions carefully. I should say that they are simply outstanding and in the proud traditions of the Faculty of Advocates in their quest for justice, their dogged and meticulous research methods and the persuasive quality of their argument...

Thus, I direct as follows: from today’s date, the last day of my tenure as Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, Thomas Muir of Huntershill will be restored to the Roll of the Faculty of Advocates.”

And that’s the end of my story. It was as happy an ending as I could manage. So, what next? A full pardon for Thomas Muir, advocate perhaps? But I leave that mission to the many passionate Muir supporters all around the world.

And I can’t do better than leave the last word to Thomas Muir himself: “I have dedicated myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause. It shall ultimately prevail. It shall finally triumph.”

And it did, Thomas, it did.

Ross Macfarlane QC’s novella, Edward Kane in ‘A Promise is a Promise’ will be serialised later this year in The Scotsman.