Insight: The gift of life for a beloved sister - Dani Garavelli

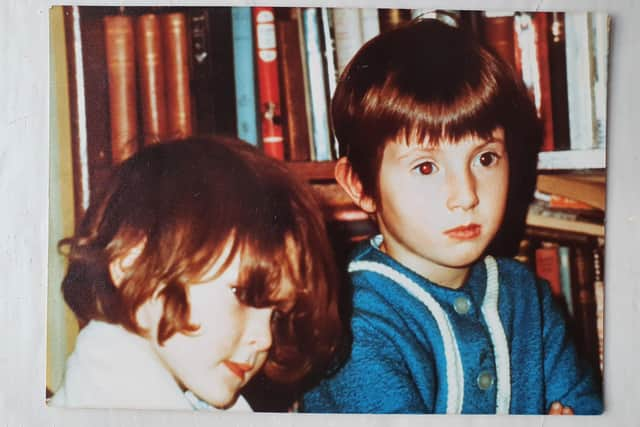

Of course, they got into scrapes. One night, in their shared bedroom, Jenny was jumping over Cat’s outstretched legs when Cat raised them mid-leap to trip her up. Jenny ended up in a stookie; Cat in a heap of trouble. But mostly it was Enid Blyton idyllic: Sherbet Fountains from the local Post Office, and reading under the duvet at night.

Years passed. The sisters grew apart. Jenny - who is two years older - was academic: good at science and languages and music, always studying. Cat began to feel a bit eclipsed. She went off to art school, forged a successful career as a photographer, but still felt she was underachieving. “It took me until I was in my 40s to realise I wasn’t stupid,” she says now, “I thought I was rubbish at everything.” There were other differences, too. Cat likes living in the country, Jenny in a town. Cat is not at all religious, Jenny plays a leading role in her local Baptist church.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJenny, 53 - a scientist - travelled with her work, then moved to Swansea where she now does plagiarism checks on an applied maths journal at the university so they were physically distant. They’d send Christmas cards, and meet up with their families once or twice a year but they weren't the types to be constantly texting. “And I was always forgetting Jenny's birthday,” Cat says.

This week, however - all going well - Cat, who is now Scotland on Sunday picture editor, will give Jenny a gift that will make up for the fractured ankle and any number of missed “Many Happy Returns”. At around 8.30am on Thursday, Covid-providing, she will make her way to an operating theatre in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary where consultant transplant surgeon Andrew Sutherland will remove her left kidney. The kidney will then be packed in ice and flown to Cardiff where - at the University of Wales Hospital - it will be placed inside Jenny. Two sisters, once joined at the hip, now bound by a five-inch organ the size of a fist.

Jenny (now Crossley), discovered she had polycystic kidney disease after a urinary tract infection when she was 31. This means her kidneys are shot through with little cysts which have been filling with fluid throughout her life. “It’s like having lots of little balloons, and these balloons squash the healthy tissue making it harder and harder for your kidneys to do their job," she explains.

In 90% of cases, polycystic kidney disease is genetic, passed down by a parent, but sometimes - as with Jenny - it is caused by a spontaneous genetic mutation. The disease is progressive, but it progresses at different rates in different people, so the doctors were not able to tell her exactly what to expect. They did warn she might require dialysis and a kidney transplant at some point, though. Cat told her from the outset she could have one of hers.

For a long time, Jenny’s condition didn’t impact her life too much. She had to watch her salt intake, and to take extra care with her pregnancies. By the time she was 40, she was on blood pressure pills and the frequency of her check-ups had increased but it remained a low-level problem only close friends were aware of. Working from home during Covid, however, impacted on Jenny’s mental health and for a short period she took antidepressants which reacted with one of the blood pressure pills. “The next thing I knew, I was fainting in the middle of the night and being taken to hospital by ambulance,” she says. “I wasn’t myself for a month or so. That’s when I started to feel unwell in a more systematic way.”

Jenny’s kidney function continued to deteriorate until September this year when it was down to single percentage figures and she was told she would need to go on dialysis. While generally effective, dialysis is time-consuming and places great constraints on people’s lives, so doctors also suggested a transplant.

“I told them my sister had already offered, and then I had a conversation with Cat to see if she had meant what she said, and she really did, and I was touched by that, “ Jenny says.

At home with her hens in her stone farmhouse in the Borders, Cat never had a second’s doubt. “I don’t feel like I am doing anything heroic or extraordinary, I am doing what feels right,” she says. “I can’t imagine not offering, then watching from a distance as she struggled with dialysis. You put yourself in another person’s shoes, and it is a horrible, horrible situation.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHer family was supportive. “It was kind of just accepted,” her partner Graham Hamilton says. “Cat goes through life in a very even strain. She is never really up nor down and tends to soak everything up.”

Though kidney transplants in the UK began in the 1960s, and now are relatively routine, they nevertheless demand a lot of potential donors. They have to undergo a series of assessments to determine if their bloods and tissue type are compatible and if they are fit enough to undergo surgery. The operation itself takes several hours and both donor and recipient require up to 12 weeks’ recovery time. The dividend, of course, is a sense of fulfilment, and the joy of seeing their loved one’s life return to normal.

Graham says he hopes he would have made the same decision, but is glad he wasn't tested. “Cat is constant, kind and empathetic and I have always trusted her with making decisions about our lives,” he says. “She cares about other people, but not in a saintly way; it’s a natural part of her personality.”

*****************************

Of the 3,486 kidney transplants carried out in the UK in the year to April 2021, a third were from live donors. At the Edinburgh Transplant Centre, which is based at the ERI, there are around 100-120 operations a year, 30-40 of which are from live donors. Live donors are always preferred to deceased donors because their kidneys start working more quickly and work better for longer, making the need for a subsequent transplant less likely.

When doctors first raise the possibility of a transplant, they ask the patient if they have any potential living donors in mind. Some people assume it must be a family member, but you don’t have to be related. Spouses often donate to one another; so do friends. Those recipients who play football or rugby sometimes find their entire team volunteering, which is great because it increases the chance of a match. You don’t have to be young. The oldest person to have donated a kidney at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary was 83. Nor do you have to be super-fit.

Jenny was lucky: her sister had already made her intentions clear, but striking up a conversation about living donation is not always easy.

To this end, the Edinburgh Transplant Centre set up the REACH scheme whereby a specialist nurse would go to the home of a future recipient to talk to extended family members. “It helps with information-sharing about donation and transplantation but it also helps to perhaps take pressure off the recipient in finding a potential living donor,” says Consultant Transplant and Living Donor Surgeon John Terrace. The scheme was paused during Covid, but it is hoped it will eventually be rolled out across Scotland.

Once a potential donor has come forward, they will start the assessment process which is overseen by the Living Donor Kidney Multi-Disciplinary Team - including surgeons, nephrologists (kidney doctors), anaesthetists, living donor coordinators, a haematologist (blood specialist and a transplant psychiatrist - and governed by guidelines set out by the British Transplant Society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first stage is a simple questionnaire about previous medical history. “There may be something glaring that would exclude a potential living donor at this stage,” Terrace says. “They may have diabetes or be on four different tablets for high blood pressure.” If they successfully clear the questionnaire, then further information will be sought from the GP.”

If there were any concerns prompted by the GP’s records, the case would be brought up at one of the weekly multi-disciplinary team meetings.

Once any concerns have been allayed, it’s time for the cross-match blood tests which check if the donor and recipient are compatible in terms of blood type and tissue. Even where the donor and recipient are not blood group or antibody compatible, donation can still take place through the UK National Kidney Sharing Scheme, allowing donors and recipients to share kidneys so living donor transplants can still take place.

Next the donor then heads for “medical day case” where much more detailed tests, including an ECG and a chest X-Ray and CT Scan are carried out. The donor’s precise kidney function is measured by injecting a radioisotope into the veins. Specialist imaging is then used to track how quickly it is excreted. Donors are required to reach a certain threshold. As our kidney function declines over the years, this threshold is age-dependent meaning older donors can have a lower kidney function and still donate.

This test also allows the doctors to see which kidney is working better. “It is uncommon for donors to have an exact 50:50 split in their kidney kidney function,” says Terrace. “If the difference is more than 10% between one kidney and the other - assuming the overall function is above the threshold for their age - we would always opt to leave the donor with the better functioning kidney. If the kidneys are within 10% of each other then anatomy plays more of a role in deciding which kidney to remove. It’s slightly more risky for the donor to dissect out and divide two or three arteries compared with one artery so we would tend to favour kidneys with a single artery.

“If the kidneys were functioning 50:50 and they had the same number of arteries, then we would tend to opt for the left kidney because the left vein is a little bit longer than the right which means the implant in the recipient is easier. But we aim to prioritise what is in the best interests of the donor in making these decisions.”

On top of the physical checks, the team will be concerned about the donor’s mental well-being. Anyone who has a history of panic attacks, substance misuse or who has, in the past, used antidepressants will be referred to the transplant team psychiatrist Dr Stephen Potts for assessment. But the team will also be keeping an eye out for more subtle signs of internalised pressure or uncertainty.

Towards the end of the process, the donor will come before an independent assessor, who will interview the donor and recipient together and separately to check for any evidence of coercion or financial inducement such as crowdfunders.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’ve done about 100 or so independent assessments over the years and explicit coercion has never come up,” he says. “Donors feeling a degree of pressure has arisen in a very small number of cases, fewer than 5%.

“Most people will say: ‘I have not felt any external pressure but I feel it is something I should do’, and if they are clearly very uncomfortable about going ahead and they are going ahead purely because they see it as an obligation they can’t wriggle out of, it might be a reason to decline the transplant.”

The independent assessor will write a report for the Human Tissue Authority which gives the final OK.

Nina Kunkel is one of the transplant coordinators whose job, she says, is a blend of air traffic controller, hostage negotiator, logistics manager and clinician. It is her job to ensure every part of the process runs smoothly. This can be stressful even when both operations are in the same centre, but it’s a massive challenge when they’re 370 miles apart. A former ICU nurse, she has gone from looking after the sickest person in the hospital to looking after the most healthy.

On Kunkel’s desk sits a Mother’s Day card from her son; inside the message reads. “I love you so much I would give you a kidney.” She says it sums everything up. Because for all the checks carried out by the independent assessor, the person donors need most protection from is themselves.

“Our job is often to rein people in a bit. You often hear them say: ‘I don’t care if my kidney function is not high enough: I want to do it.’ Because it’s somebody they love,” says Kunkel “It’s humbling to sit in the room with these people and hear that. But donors are already taking a risk by deciding to live with a single kidney; we have to make sure that risk is reasonable and not above and beyond.”

Kunkel says the worst part of her job is having to tell people their kidney function is not high enough, especially if they are the only potential donor. If that happens the recipient will be placed on the waiting list; the average waiting time is two and a half years.

“But mostly my job is brilliant,” she adds. “Sometimes, I will go into the clinic and the recipients who had their transplants two months ago are back for their check-up and they look completely different. It’s mind-blowing how well they can become straight away.” Kunkel did a 55-mile cycle with one patient six months after he got his new kidney. “I couldn’t keep up,” she says. “He was home in the bath before I finished.”

**************

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe assessment process proved relatively straightforward for Cat. She only just made it under the wire in terms of kidney function - hers was 80%, the minimum for her age - and some of her anti-HLA antibodies reacted with Jenny’s, but not enough to raise major concerns.

A second set of cross-match blood tests - done a fortnight ago to ensure nothing had changed - suggested all was well and the final clearance from the Human Tissue Authority is expected any day.

Waiting to find out if she would be accepted took its toll, though. There is an internalised weight of expectation, and no way to hurry things along. “All the way through I felt as if one step away from being discounted, which is quite stressful,“ she says.

She has experienced this sense of being at the mercy of medical procedures before. When her elder daughter Eve turned 13 she was diagnosed with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome which causes the heart to beat abnormally fast for periods of time. Eve, now, 19, underwent two unsuccessful heart ablations - a process that involves a three-minute freeze at -80C destroying a tiny faulty bit of the heart while it is still beating - before the third one worked in September 2017. “When something like that is happening it becomes the focus of why people are phoning you. They want to find out what the latest is and to ask whether you have chased up this or that. So this time I’ve been quite careful just to keep a bit of distance.

"My family are concerned for Jenny, and they want things to happen quicker, quicker, quicker but you are in this slow process and you have to go through it one step at a time.”

In a Victorian terraced house a few blocks from Swansea seafront, Jenny has been having a tough time too.

When I first spoke to her in early October, she was tired, suffering from cramps and nausea and on a strict diet on which most snacks and treats were forbidden. The following day she was undergoing surgery to have a port installed so she could start peritoneal dialysis - a process in which waste products are cleared from the blood using a special fluid inserted into the abdomen via a tube.

Peritoneal dialysis can be done at home, but it’s still incredibly time-consuming. You always have fluid in your abdomen exchanging and you have to empty it and replenish the fluid up to four times a day. “They say it takes about 45 minutes,” Jenny told me. “You have to warm up a bag of fluid, drain the stuff that’s already been waiting in your abdomen, flush out the lines that fill your abdomen with fluid at body heat, disconnect everything, put a sterile cap on the tube that’s coming out of your tummy and put a new dressing on.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the end, though, it proved difficult. “The draining wasn’t working quite right and I was in pain,” she says. “The tube was getting moved around inside me, and then it went completely the wrong place. Instead of pointing down, it was pointing up to my ribs.”

The problem was caused by constipation - a symptom of kidney failure - but the laxatives Jenny was given didn’t make enough of a difference. The doctors said the little bit of dialysis she had undergone had improved her bloods and that, since her transplant date was just weeks away, they would not persist.

This is supposed to mean a week without medical procedures, but a couple of days later Jenny sends a photograph of her in hospital, having iron and EPO, a chemical which helps the body convert iron into blood cells, infused directly into her bloodstream to tackle anaemia.

Jenny says she feels better than she did, but her energy levels are still low. The day I talk to her she has been for a short walk to the local park with her friend, but she can’t work or drive or socialise indoors.

She can’t go to her church either, but she has been watching the services online. She says her faith has helped her cope with the worst of it.

“Being this ill is battering at my identity because there’s so much I can’t do,” she says. “In church I used to preach sermons, I used to sing, I used to lead worship and prayers for the congregation. I also used to travel into work and meet lots of people and now I am signed off. It’s like what am I useful for? I can’t even do many household chores. So you say: ‘Is there any value to me?’ And in that sense religion helps because I know I am a child of God and he values me just for me.”

In a way, volunteering to donate a kidney is an act of faith: in medicine, in the future and in one another. Cat wants to give her sister back her life, but also perhaps to reset a relationship that got stuck in a sisterly rut built on self-doubt.

They already seem more bonded by the experience. Knowing they will be out of commission for up to 12 weeks after the transplant, they have been busy buying each other Christmas presents.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJenny has splashed out on a hamper of Wensleydale cheese for Cat and Cat has bought Jenny upmarket chocolate from a Scottish small food business.

“The operation feels unreal and I am taking it day by day so as not to become hysterical about it,” Jenny says. “Part of me is scared about it and how I will feel afterwards, part of me is just really, really grateful to Cat for putting herself through it, and part of me is starting to feel a bit more hopeful and excited about how things will be afterwards.

“Imagine I can actually eat that Christmas chocolate: how fantastic will that be?”

All going well, Scotland on Sunday will be following Cat’s kidney as it makes its journey from her to Jenny. Read about it on Sunday November 28.

For more details: https://www.organdonationscotland.org/living-donation

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.