Edinburgh murders: The Demon Frenchman of George Street

He is likely to have received some degree of a university education, since he knew excellent Latin and Greek, and good English and German, and since his medical knowledge was better than what could be expected from an uneducated layperson. In 1864 or 1865, he came to Edinburgh, where he took a comfortable house at 81A George Street living on the second and third floors above a shop. He advertised for private pupils in the Scotsman newspaper of January 4 1865.

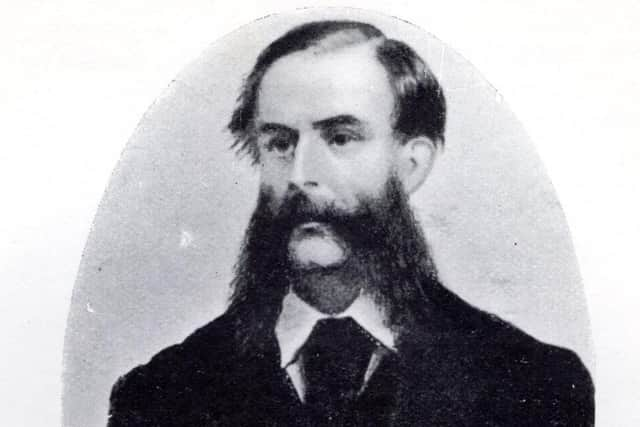

Since Eugène was a rather handsome, elegantly dressed man, and obviously a person of learning and culture, he was employed at several schools, including the private Newington Academy, where he began work in December 1865. Here, he met the pretty 15-year-old schoolgirl Elizabeth Cullen Dyer, who came from a distinguished Edinburgh family. After a short acquaintance, Chantrelle seduced and impregnated her, and when she showed obvious signs of pregnancy, a shotgun marriage ensued on August 11, 1868. Elizabeth moved into 81A George Street, where she gave birth to her son Eugène John later the same year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdInitially, Eugène and Elizabeth Chantrelle got on well together. There was a schoolroom in the house where he taught private pupils who wanted to brush up their French or Latin. But soon the marriage was breaking up. Chantrelle drank French wine and champagne with enthusiasm, but he also developed a taste for the Scottish national drink, emptying a bottle of whisky per day.

He beat and mistreated Elizabeth, and sometimes kicked her out into the common stair at night, forcing her to take refuge in the flat below. He cursed her in bloodcurdling terms, saying that he would shoot her with a loaded pistol he used to carry around, or that he would make use of his medical knowledge to kill her with a poison that could not be detected. Fearful for her life, she wrote to her mother complaining of her abusive husband, but old Mrs Dyer advised her to stay with him. There were by now three little Chantrelles to feed, and she did not want the family to be split up.

In October 1877, Chantrelle took out £1000 policies on both his own life and that of his wife. Elizabeth was fearful that he would murder her now when her life was insured, but her mother pooh-poohed her concerns. On New Year’s Eve 1877, everything seemed normal in the Chantrelle household. The jovial paterfamilias had lately run into debt due to his extravagant life, but still he drank wine and champagne as if it like if it were water, and was a regular at a fashionable New Town brothel.

On the morning of New Year’s Day, Elizabeth felt a little unwell, complaining of a slight headache. Chantrelle sent his eldest son out to purchase a duck for dinner, but Elizabeth vomited and did not eat anything. The following morning, the servant Mary Byrne rose before seven to make a cup of tea for her mistress. Elizabeth was lying on the bed moaning piteously, and the pillow and bedclothes were stained with vomit. In the parlour was a large, empty whisky bottle.

When Chantrelle was roused, he went to see his unconscious wife, who did not stir. He summoned one Dr Carmichael who arrived at 8.30am. He could smell gas in the room and suspected coal-gas poisoning. He brought some brandy to inject as a stimulant, but the thirsty Chantrelle drank much of the contents of the bottle when the doctor was not looking. Dr Carmichael called in the police surgeon Dr Littlejohn, and Mrs Dyer brought her own family doctor along to see Elizabeth, who was now deeply unconscious. The doctors tried artificial respiration but to little avail, and the patient died at the Royal Infirmary soon after.

The histrionic Chantelle exhibited grief and rage, accusing the doctors of murdering his wife. When the gas company was called in, they found that a gas pipe behind one of the shutters of Elizabeth’s bedroom had been wrenched loose by some person. But the doctors no longer thought the symptoms were those of coal-gas poisoning; Dr Gordon, who had seen many poisoning cases before, instead thought the patient had died from the administration of some narcotic poison. And indeed, the post-mortem examination demonstrated the presence of opium in the vomit on the patient’s nightdress.

When Elizabeth was buried, there were distressing scenes when the frantic Chantrelle tried to fling himself into the open grave. But after it had been established that on November 25, 1877, he had purchased sixty grains of opium, he was arrested for murdering his wife. A strange matter was that her urine had an alcoholic odour, suggesting that he might have administered the poison in some of the whisky from the empty bottle found in the parlour. The loose gas pipe had just been a clumsy attempt to make the death look like an accident, so that he could cash in the life insurance money without any demur.

The trial of Chantrelle began on May 7 1878, before Lord Moncrieff. The maid Mary Byrne gave her damning evidence clearly and without contradiction. There was a painful interlude when the little boy Eugène John described how his papa used to call mamma bad names, swear at her, strike her, and make her cry. A former maid in the household described how, in 1876, she had rescued Madame Chantrelle from her abusive husband; when they had reported the matter to a police constable, the furious Frenchman had screamed, prophetically as it turned out, ‘I will do for the bitch yet!’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe medical evidence pointed in favour of opium poisoning. The defence had a difficult task, mainly concentrating on finding witnesses that corroborated some of the prisoner’s statements, and persons who could testify that he was not always violent and abusive to his wife. The jury returned a verdict of guilty and Lord Moncrieff sentenced the prisoner to death.

For a scoundrel of his calibre, there was no hope of a reprieve: after hearing that he was a doomed man, the demonic prisoner had exclaimed, ‘Would that I could but place a fuse in the centre of this earth, that I could blow it to pieces, and with it the whole of humanity. I hate them.’ When asked, on the night before the execution, whether there was anything he wanted, the prisoner said, ‘Send in three bottles of champagne and a whore’, a request that was denied him.

Unrepentant to the last, he breakfasted on coffee and eggs, washed down with a glass of brandy, before smoking a cigar. Chantrelle was hanged by the executioner Marwood on May 31, the first execution in Scotland to be conducted in private, inside the prison grounds. The Edinburgh murder enthusiasts swarmed like bees on Calton Hill, but they were unable to see more than the Black Flag being hoisted from the turret flagstaff in the bright spring sunshine.

This is an edited extract from Jan Bondeson’s book Murder Houses of Edinburgh, published by Troubador