Dani Garavelli: Scottish artists speak of crisis in funding

The masks themselves - pink, wax faces caught in various expressions of eternal repose - are laid out next to her open car boot. They were tests for work later purchased by the British Council. Borland is coy about how much the British Council paid. “Let’s just say ‘museum prices’,” she says. But the masks on sale here can be snapped up for just £90.

Borland is one of more than 80 artists taking part in the two-day Art Car Boot organised by Patricia Fleming, whose eponymous gallery represents Borland and other big names, including Jacqueline Donachie and Illana Halperin.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNext to Borland are bright, brash works by her husband and former Soup Dragon Ross Sinclair, best known for his Real Life project which began when he had the words REAL LIFE inked across his back in 1994. You can buy a Ross Sinclair beer mat for pennies, but a framed I Love Real Life hand-pulled silk screen print will set you back £400.

Most of Scotland’s contemporary art royalty are represented at SWG3 today. Opposite Borland, Claire Barclay, whose solo exhibition, Thrum, is on at the Metropolitan Arts Centre in Belfast, has propped a row of paintings against the side of her silver hatchback. Elsewhere, there are masks and T-shirts by Turner Prize winners Martin Boyce and Douglas Gordon.

Taking their place alongside the old guard are less established artists. Isabella Shields is director and co-curator of 16 Nicholson Street, a gallery which focuses on emerging talents. She shows me pinhole camera prints by Glasgow-based Polish artist Aga Paulina Młyńczak inspired by a letter from her grandmother. “They are part of a larger project about language and history - what it feels like to be alienated but also embraced by a new community,” Shields explains.

She also talks to me about a series of cyanotypes of women who took part in the Crofthead mill strike in the 1910s by Japanese artist Natsumi Sakamoto. “These portraits are taken from one single landscape photo of the women involved - none of whom are named or recorded in history,” she says. “That’s what [Natsumi] wanted to bring out - that they were all individuals with their own reasons for being involved.”

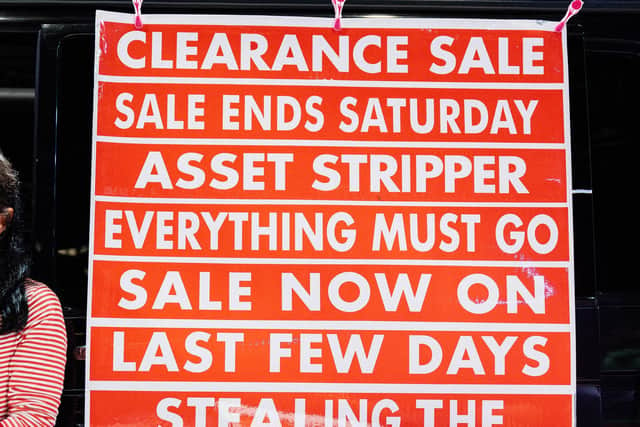

Though the Art Car Boot, an annual event back after a two-year Covid hiatus, is affordable and informal, it is carefully curated. Fleming eschews shortbread tin representations of Scotland so, while it isn’t “high-end” there isn’t a Tunnock’s Teacake or Highland cow in sight.

“Artists here are invited by Patricia, so you know you will be in excellent company,” says Borland, who is also Professor of Fine Art at Northumbria University in Newcastle. “It’s not a jumble sale by any means. The great thing is you can show work in progress, work that didn’t turn into something or that might have turned into something else, and share stories.

“I do lots of talks and teaching and lecturing, but there is nothing quite like this - the accessibility of it, artists just having a chat.” Borland has been giving out flax seeds in connection with a project on linen she is working on. “There are people who come because they know my work, but many others don’t know who I am - something just catches their eye,” she says.

Donachie, who couldn’t make the Art Car Boot this year, recalls a previous occasion when a man bought one of her Fruit Market catalogues for his sister. It turned out his sister was writing her dissertation on Donachie’s work. “I think it is great because people who are nervous about buying art that isn’t paintings of cows or landscapes can buy it here,” she says. “It’s not off-putting.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“And in terms of meeting people, it’s brilliant. When you think of all the work Creative Scotland does around engagement. Well, in SWG3 there are well-known Glasgow artists - artists you might be writing your dissertation on - standing at their cars for two solid days, talking to strangers about their work.”

*********

Scotland - and Glasgow in particular - has been a mecca for contemporary artists since the 1990s. Back then, students from David Harding’s ground-breaking Glasgow School of Art environmental art course, including Gordon, Donachie, Borland and Nathan Coley, took the city’s post-industrial landscape by storm.

Bonded by their similar backgrounds and their love of the thriving indie music scene, they formed a tight-knit and mutually supportive community, congregating at the artist-run Transmission gallery.

Six Glasgow-based artists - Gordon, Boyce, Martin Creed, Simon Starling, Richard Wright, and Susan Philipsz - went on to win the Turner Prize, with many more short-listed, an explosion of talent dubbed “the Glasgow Miracle”.

It was a misnomer, which underplayed the hard graft which went into the city’s evolution into a beacon of contemporary art, but their success was self-perpetuating. More and more visual artists pitched up in Glasgow, attracted by its reputation and the availability of studio space.

In 1997, another environmental art course graduate, Toby Webster, co-founded the hugely successful Modern Institute which brought Glasgow artists to the international market. The Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art, which began in 2005, also focused attention and created new opportunities in the city.

What is clear from a morning at the Art Car Boot is that there has been no waning of talent in the intervening years. “Glasgow has so many artists,” says Donachie, who now lives with her artist husband Roddy Buchanan and their three sons in Lenzie.

“If you come to study at the Glasgow School of Art, you can stay on and live your whole life amongst artists. You can rent a flat in Govanhill, play football and basketball with artists, have a bar in Shawlands [all your artist friends] drink in. I don’t think you can do that anywhere else in the UK outside London.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd yet - despite its vibrancy and the UK and Scottish governments’ insistence that culture will be at the heart of the pandemic recovery - many of those in Scotland’s visual arts community are downbeat.

Brexit has hit artists across the country, increasing the cost and complexity of moving people and goods across the world. Yet the UK Department of Trade has failed to provide post-Brexit funding to support artists with these challenges and, critics claim, there is no Scottish government export strategy around the sale of art works internationally.

Though the SNP moved quickly to help artists during the pandemic, bringing in bridging bursaries and hardship funding, artists still struggle to make ends meet.

Other countries have boosted spending on the arts in the wake of the pandemic. In August 2020, the then German chancellor Angela Merkel increased the fund for the state purchase of art from contemporary artists six-fold from 500,000 Euros to three million Euros. And last week, the new president of South Korea, Yoon Suk-yeol, announced a $3.7bn fund for film, TV, art and other cultural projects ahead of the September debut of Frieze Seoul and the opening of the Busan Biennale.

Meanwhile, cultural funding in Scotland has been at a standstill for the best part of a decade, with the budget for 2022/2023 showing a real-term cut in spending on Creative Scotland and other arts.

Local authorities are similarly stretched, with real-term reductions in commissioning budgets for council-run galleries, while the decision to shift responsibility for culture and sport to the arms length external organisation (ALEO) Glasgow Life has, critics claim, resulted in a loss of focus and expertise.

Despite the financial bail-outs, the pandemic has taken its toll, with many art school degree shows - normally a launching pad for emerging talent - cancelled during Covid. In the wake of lockdown, Fleming took the decision to close her physical gallery space on Oxford Street, Glasgow; she now operates online.

Overall, artists believe there is a mismatch between Glasgow’s acknowledgement of the role art plays in driving its economy and the extent to which it understands how to nurture and support the sector.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I feel organisations like the Glasgow School of Art and [Glasgow city council] have milked the ‘Glasgow Miracle’ but not put anything back,” Donachie says. “They have milked my generation for their own ends. On the one hand, they see how important it is because they use it and talk about it, on the other they don’t appear willing to invest in it.”

**********

The challenges facing artists are difficult to analyse because they come from all directions. Some are structural, some political, some cultural. Some - such as those relating to the pandemic - apply across the cultural sector, while others are specific to the visual arts.

Fundamental to their precarity is the fact they cannot sign on. Or rather, if they do, they must spend 35 hours a week looking for work when they could be creating.

This was not always the case. The “Glasgow Miracle” generation were eligible for benefits under various schemes. Between 1991 and 2000, Fleming ran FUSE, an initiative which provided them with free studio space and a materials allowance for a year. “I re-educated employment services in what an artist was," Fleming says. "Instead of an employment adviser looking blankly, you could sign on with ‘artist’ as your job."

Since 2019, artists in Ireland have been allowed one year on benefits without pursuing work in order to develop their craft.

But here in the UK, welfare rules mean most emerging artists are also working part-time as chefs, bar tenders or baristas .”There’s less money around,” Donachie says. “People have less time because they have to work longer hours in shitty jobs and that creates less energy.”

The Scottish Government supports the concept of a Universal Basic Income, which would give everyone - including artists - a guaranteed monthly income, increasing stability. But the UK government has rejected it on the grounds that “it does not target help to those who need it most”.

The Art Market 2022, a report by Dr Clare McAndrew, founder of Art Economics, showed Brexit was already having a negative impact. While the global art market bounced back to pre-pandemic levels in 2021, the UK art market’s recovery was less pronounced and it remained significantly below the 2019 figure. Imports were down by a third. The report said that, while much of that incoming trade went to the US, some may have bolstered EU markets. Sales in France rocketed by 50% to $44.7bn, while Germany, Spain and Italy also saw double digit growth in value.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese are some of the pan-UK challenges. But there are more local ones, too. A constant bug bear for Scottish artists is the lack of a national collector base. No-one seems sure why, but it can't have helped that, when the city's Gallery of Modern Art opened in 1998, it ignored the new wave of Glasgow artists. That glaring omission has been rectified, but perhaps lasting damage was done.

“There was a time when people in Scotland did buy contemporary art,” Donachie says. “The likes of Steven Conroy and Alison Watt sold out their degree shows; everyone went round and bought their stuff. Now [those with money] buy Vettrianos.

“I think there’s a lack of education around what constitutes contemporary art. There’s an assumption about what people will like, so I think what's needed is exposure and a realisation that it is not totally unaffordable. You have to nurture the collecting habit but once people go down that road, they get a real love for it.”

With few Scottish collectors, artists rely on sales elsewhere, yet those who are not represented, or who are represented by smaller galleries, struggle. Fleming says it’s difficult and it’s really only the Modern Institute which has consistent access to the international market through fairs like Frieze in London and New York, and Art Basel. Even if applications from smaller galleries like hers were successful, the smallest booth costs between £6,000 and £7,000.

“The Scottish Government should be helping us to bridge that economic gap, so we can go to those fairs in the same way those in design and the games industry go to international expos,” she says.

Everyone agrees the Modern Institute is a shining example, they just worry its success suggests the sector is doing fine and has no need of further support. Fleming and others feel there is a dearth of smaller commercial galleries, with some faltering through lack of support. Sorcha Dallas closed her gallery doors in 2011 after she lost her Creative Scotland funding.

“We need a better private gallery scene,” Donachie says.

Glasgow's High Street is currently peppered with empty buildings. “You could imagine it with 10 commercial galleries and enough of a clientele within Scotland to keep them going,” Donachie says. “But people have tried; it’s very difficult without some kind of subsidy.”

Glasgow City Council has invested heavily in the refurbishment of the recently re-opened Burrell, which attracts many tourists. But there’s a perceived lack of support for contemporary artists - a decline some believe began with the shifting of responsibility of sport and culture to Glasgow Life in 2007.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When I used to do talks internationally or in London, they would say: ‘Why has Glasgow got this huge focus?’" Fleming says. "I would answer with pride that it had a great supportive city council. I haven’t been able to say that for years.”

It probably doesn’t help that Glasgow Life is in a state of transition, with new chief executive Susan Deighan taking over from Bridget McConnell, and new chair Annette Christie taking over from David McDonald.

Christie, who is also the city council’s convenor for culture, sport and international relations, is nothing if not enthusiastic. She confirms the Glasgow International - a biennial event which attracts influential figures from the arts world and adds an estimated £1.5m to the city’s economy - will take place again in 2024 after a three-year Covid-related gap, and says this time it will be shaped by the artists themselves.

“We are also looking to transform the city centre through the Avenues project,” she says. “We want to create an ‘avenue of the arts’ - an experience for both the Glaswegians and visitors to our city, and I would very much want our contemporary artists to be part of that.”

And yet, the sale of many of the council’s buildings to another ALEO, City Property, has created more hurdles. Fleming remembers a time when artists prepping for a show would be given the keys to empty buildings, returning them when they were finished. But City Property operates on a commercial basis, making it less likely arts groups will be given cut-price rates. It also means arts groups already located in such buildings face rent rises. Those at Trongate 103 - a six-storey hub that houses the Transmission Gallery, the Glasgow Print Studio, Street Level Photoworks and Sharmanka - were given a reprieve during the pandemic, but a review is imminent.

Fleming compares what she sees as Glasgow’s lack of direction to the way in which Maria Balshaw helped shape arts policy in Manchester until she left to become director of the Tate in 2017.

Balshaw’s dual role as director of the University-based Whitworth collection and director of the city’s galleries allowed for an unprecedented collaboration between the two institutions and the city’s historic and contemporary collections. Others look to Dundee where Duncan of Jordanstone College is in the ascendancy and a focus on contemporary arts has delivered, among other things, the new V&A.

The starting point for Dundee's strategy was a recognition that a strong cultural offering was vital if it was to retain its highly-skilled medical tech workforce. This led to the setting up of Creative Dundee, investment in Dundee Contemporary Arts and the development of an international programme. The same thinking drove the establishment of the V&A and is now propelling the ambitious Eden Project Dundee which will transform the old gasworks.

*********

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnother problem besetting the contemporary arts sector in Scotland is the lack of data on its contribution to the economy. There are reports that provide figures about the value of the UK contemporary art market (but do not include a break-down for Scotland) and reports which provide figures for the value of creative industries to Scotland (but do not provide a break-down for contemporary art).

Yet - as Fleming points out - how can you make effective policy without analysing those numbers? She would like to see such a report commissioned and the setting up of a body similar to Scotland Food and Drink, a pioneering agency which enables the government and the industry to work side by side. It has helped drive growth in the sector, now worth £15bn.

Culture Counts, a network of arts, heritage and creative industry organisations, is also lobbying for an office of cultural exports, sitting within the Scottish government, to help support all “creatives” from musicians struggling with carnets - passports for goods - to those in the craft industry struggling with individual exports.

Despite the challenges they face, many artists with Scottish connections are continuing to thrive in a still-lively community. Most recently, the six-strong shortlist for the Film London Jarman Award 2022, included two Glasgow-based artists: Jamie Crewe and Alberta Whittle. In 2020, Crewe won the Margaret Tait Award, Scotland's most prestigious moving image prize for artists, while Whittle was one of the artists representing Scotland at this year’s Venice Biennale.

The Art Car Boot may be over for another year, but there is still plenty going on. A director is now being sought for Glasgow International 2024; and 16 Nicholson Street has put out an open call for individuals and groups to take part in its 2023-24 curated programme.

Lots of people want to make work, lots of people are creating their own opportunities. Scotland is still punching above its weight. But what artists want to see is a closing of the perceived gap between Scottish government rhetoric and spending on the visual arts.

“The country benefits so much from the visual arts in terms of its well-being, its economy and its international reputation,” Fleming says. “We just want to see a strategy and commitment that reflects its true value.”

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.