Scots speakers should learn from Gaelic and feel no shame – Alistair Heather

The news that Gaelic will now become the default first language of education in Na h-Eileanan Siar is a remarkable positive step. It is policy reacting to a community preference for teaching to be conducted in the native language of the area. It has taken years of grassroots activism and pressure to bring this change to pass.

For those 1.5 million of us that speak Scots in Scotland, and especially those in Scots heartlands, we should learn lessons from this Hebridean development and apply them very quickly to Scotland’s other indigenous spoken minority language.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are many parallels between the plights of Scots and Gaelic. Both have thrived as national languages at one time, and both continue to have large heartlands of speakers today. Both have been, and in some quarters continue to be, methodically delegitimised, othered and devalued.

The Education (Scotland) Act of 1872 stipulated that English should be used in all schools, regardless of cultural hinterland. Beatings were administered for children using their native tongue in schools, be it Scots or Gaelic.

This was part of a process of linguistic colonisation and it has had long-term negative impacts. Tell a minority group their language is primitive or uncouth enough times, in school, in newspaper print, in books, they’ll eventually start to believe you. This process engendered an internalised shame for many Scots and Gaelic speakers. These measures curtailed the growth of the languages and negatively impacted the attendant culture.

'A wealth of language'

In the Gaeltacht, as in inner-city Glasgow, one result of this suppression was folk not teaching their offspring Gaelic or Scots as it would "hold them back in life". Speaker numbers plummeted, and some distinct dialect groups died out.

This initiative in the Western Isles seems to signal a significant moment in the recovery process for Gaelic, and for Scotland.

Learning an indigenous language has many very positive effects, as Gaelic singer Margaret Macleod of Na H-Oganaich told me.

“The best legacy my parents ever gave me was the Gaelic language and its culture and heritage,” she said.

“We have such a wealth of language, a vocabulary that explains who we are. It gives us an identity and a history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The people that are learning Gaelic don’t just learn Gaelic, they enjoy learning all the stories and the culture. When I teach Gaelic I talk about time in Lewis, and cattle and all that. They love all these stories.”

Scots-speaking heartlands

This message is gaining traction in Scotland. By ensuring the health and expansion of a language, we help strengthen a line of cultural communication that links the past to the present, through which rich heritage and traditions can be passed, and identities secured.

There is still time to intervene in Scots-speaking heartlands, where significant speaker numbers exist. In Buckie, the fishing town on the Moray Coast, 62.5 per cent of the population speak Scots, according to the 2011 census. In the city of Dundee, the figure is nearly 40 per cent. In Greater Glasgow, there are at least 200 000 speakers, likely more.

In the Borders, Ayrshire, Shetland, Lothians, hundreds of thousands of people carry their relationships, traditions, identities around in a language that is increasingly threadbare and calling out for status and support.

Our educational provision for Scots makes for extremely bleak comparison to Gaelic, despite recent improvements.

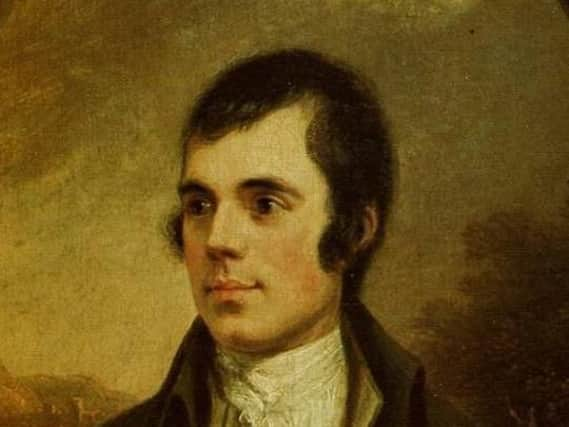

Very few Scots works of literature are available for study at higher level in schools, and what’s there is not popular. The work of Rabbie Burns is the second least-favourite Scottish text for National 5 classes, for example, with English-only texts preferred.

Education Scotland currently only provides one single Scots Language Coordinator to cover the entire country. He does a superb job, but it simply should not be down to a single individual to cover every school from Stranraer to Shetland.

Little more than lip service

There are currently no plans to introduce so much as a Scots-Language Higher, let alone follow the Western Isles example and introduce Scots Medium Education.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is not solely due to political apathy, but because Scots-speaking communities have not yet fully recovered confidence in their language.

The change in Gaelic Medium Education in the Hebrides has come about not solely because of policy change, but because of cultural change. Communities are demanding Gaelic education and they are getting it.

This seems to indicate that the Gaeltacht is beginning to shrug off internalised shame. Scots communities must work towards achieving the same. Without first accepting the value of Scots, our politicians will continue to pay it little more than lip service.

Scots is a language that exists here, and is the mother tongue for a tremendous number of people. We need to accept that and start to celebrate it. As Margaret found with her Gaelic, the language is a vehicle through which our identities, cultures, stories, songs, jokes and sayings are passed on. Without it we are denuded.

As Margaret said: “With Gaelic, and the same with Scots, you hear people knocking it. Why not enhance one’s knowledge by accepting what we’ve got in Scotland, rather than deny it? Embrace what Scotland has to offer.”