Scots is a language and not ‘slang’ – Alistair Heather

Being told to “speak proper”, having your language mocked on national TV and derided as incomprehensible across the UK and the world. This is the typical fate of the speaker of Glasgow Scots, the Glaswegian dialect of the Scots language. These prejudices have contributed to a complex pattern of ‘code-switching’ in which a speaker might use Scots with friends, but move along a language continuum towards Scottish Standard English when in a classroom, a job interview or talking on the phone.

You could imagine newcomers to the city and country struggling to navigate this linguistic quicksand. ‘Yes’ and ‘aye’ are commonly used in the city, but pinning down precisely where, when and how to use one over the other would be a tricky lesson to teach, let alone assimilate into practise. Yet according to a recent study by Dr Sadie Ryan of Glasgow University, young migrants to the city are adopting not only elements of the Scots language, but are quickly learning how to code-switch like native speakers based on their audience.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Ryan was first put on to the linguistic challenges migrants to Glasgow faced when working with asylum seekers. They were studying English textbooks but very quickly realising that the patterns explained in the book were not those being spoken outside. “Words like ‘aye’ and ‘cannae’ were common in the streets outside but went unexplained in the textbook,” she said.

To investigate the ways in which young migrants adapt to this linguistic environment, Dr Ryan went to a high school in the East End of Glasgow. It is a working-class area that until very recently had low immigration and a close-knit linguistic community which had sustained a relatively dense Scots lexis in common usage. Since the expansion of the EU in 2004, the area has seen a marked increase in migration from Eastern Europe, with concomitant impact on the demographics in the classroom.

The study looked at language, and also specifically at code-switching. This is something we as Scots do all the time, varying our accent and vocabulary to match with our perception of what is ‘proper’ for each situation.

To gain insight into code-switching, the kids were recorded in three different social situations to see how they responded linguistically to different listeners. An after-school club was set up, where the kids were free to play and joke with their pals. They did loads of activities like drums, make-up, arts and crafts. They were equipped with headset mics to capture the audio. Then they were recorded in conversation with Dr Ryan, a more formal setting. Finally, they were recorded in the classroom doing school work.

The Glasgow Scots features Dr Ryan was looking out for were things such as Scots negation. That is words such as cannae, wilnae, dinnae, didnae, saying “I’m no daein that” as the equivalent of the standard English “I’m not doing that”. Dr Ryan was also looking at glottal stops. This feature – the ‘dropping’ of the t in the middle of words – is actually fairly complex. “Although people can see it as an absence, it involves the contraction of the vocal cords to create a distinct sound, so is better seen as alternation between different sounds. Its use too is complex. It can only replace t-sounds when they occur in very specific places in speech, yet no language learning textbook will tell you which places it can occur in.”

The results from the after-school club were interesting. When wearing a mic, the kids would spend five minutes tearing about, putting on funny voices and kidding on they were American. When they began to settle down, however, it was clear that, amongst themselves, these young immigrant and Glasgow-born kids, living and learning together in a working-class part of Glasgow, were using Glasgow Scots features regularly in their conversations. Regardless of the country of birth of the children, Scots negation and glottal stops were common.

The after-school club also revealed examples of the newcomer pupils’ mother tongues contributing to the linguistic repertoire of the group. For example, a wee guy with a Polish girlfriend had learned “I love you” in Polish. And a group of pals – Polish, Lithuanian and Scottish – would use bits of Scots, bits of Polish, bits of Scottish Standard English to communicate. Dr Ryan witnessed during this part of the study a lot of effort from the Glaswegian-born kids to integrate with and welcome the newcomers, which is great to hear.

The second and third parts of the study – the interviews and the recordings made in the classroom setting held with the pupils – were also revelatory. The ability of non-Scottish born pupils to code-switch between Scots and Scottish Standard English was as good as their Scottish-born classmates.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConversations with pupils of various backgrounds revealed that they saw the Scots words as being ‘slang’. For example, saying ‘aye’ is the slang for ‘yes’. This is less positive news as it does seem to indicate that prejudices about the Scots language are being transmitted along with its vocabulary and usage.

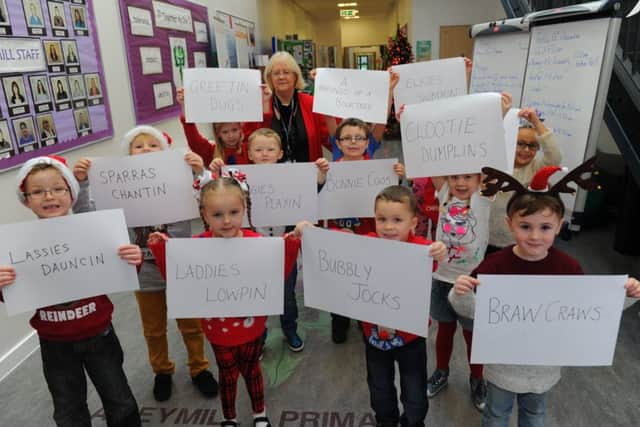

The Scots language is spoken by around 1.6 million people, according to the 2011 census, yet bizarrely it has little or no place in many schools outside of Burns Week. The impact of this lack of legitimacy in school is perhaps seen in the attitudes of the pupils learning and using the words who see it as of lower status. Dr Ryan saw pupils with negative perceptions of their own voice, with one saying “I wish I had a different accent” and another that “we don’t really speak proper round here”.

This study has revealed that Scots plays an important role in the social integration of newcomers into the school environment. It is also playing a role in identity formation.

As this is the 2019 United Nations Year of Indigenous Languages, it is a great time to reassess and improve our national relationship with the Scots language. Excellent studies like that conducted by Dr Ryan can reveal the importance of Scots to our identity and its centrality in our everyday communication. It would be a positive to investigate further the role of Scots in social integration and look at ways to use it to boost linguistic confidence both in and out of the classroom.

More positive still would be for us just to learn to speak it with confidence ourselves, to take away the strange cringe or shame some of us have about these native words, this language o oor national bard an the language o oor scuils the day. Let’s breenge intae 2019 wi a bit mair smeddum whan it comes tae the Scots language, whitiver dialect ye speak.

Dr Sadie Ryan’s new language podcast Accentricity is available on podcast apps and at accentricity-podcast.com

Alistair Heather is on Twitter @historic_ally