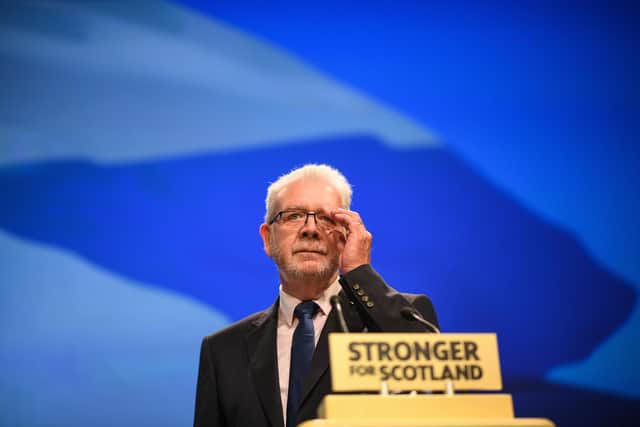

Michael Russell's appointment as chair of Scottish Land Commission is a sign of how SNP has silenced dissent – Brian Wilson

You may not have noticed, but the last day’s business at Holyrood before they went off for Christmas was changed at short notice. This was to accommodate a vital debate on appointing Michael Russell, until recently president of the Scottish National Party, as chairman of the Scottish Land Commission.

This duly happened with all SNP and Green MSPs voting for him and all the rest voting against him. Whatever bipartisan credibility the Scottish Land Commission had previously, it disappeared with that division which was a product of both process and the personality involved.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOpposition MSPs – as well as crying “corrupt” and “cronyism” – were puzzled by the urgency since the appointment does not take effect until mid-March. This is because, in September, the Cabinet Secretary, Mairi Gougeon, altered the timetable for no very obvious reason, by extending the appointment of the current chairman, Andrew Thin.

Mr Thin, a fixture on the Scottish Government quango circuit, then became a member of the panel which recommended the appointment of Mr Russell, along with one of Ms Gougeon’s civil servants. There were seven applicants for the post. It is not known if they even bothered to interview any of the others.

Public bodies run by ‘trusties’

People who take a serious interest in land reform have been understandably dismayed by the appointment. The Scottish Land Commission has not set any heather on fire but with radical leadership could at least have challenged the inertia which has characterised the SNP’s tenure at Holyrood. My sympathy is with the other board members.

It is an episode that highlights one of the great democratic deficits which has evolved in Scotland over the past 16 years. There is no public body accountable to the Scottish Government which is not in the hands of ‘trusties’ who are there on the clear understanding they will not rock any boats. The quango appointments system takes care of that.

Just as with the weakening of local government, Scotland is the poorer for this retreat into acquiescence. We need public bodies with specialist knowledge which are prepared to speak out publicly in defence of their sectoral or regional interests. That should be seen as a strength of government rather than a threat. Yet when was the last time it happened?

As a small repertory company of favoured faces shifts effortlessly from one quango to the next, the clear message is that life on the circuit is wholly dependent on accepting the party line. The inevitable result is a slide into the mediocrity of consensus and a fear of standing up to ministers or civil service.

In fairness, the roots of the quango malaise go back beyond devolution or the SNP. They’ve just grown steadily more pernicious. When I was in the pre-devolution Scottish Office, it became apparent that civil servants controlled the appointments process, weeding out applicants for public positions whom they regarded as potentially troublesome.

Nolan Committee’s recommendations

At the same time, there were well-connected individuals who were put forward for every post that became available. One of these names is still turning up as chairman of this and chairman of that 25 years later, never having caused a ripple along the way – and still just as well connected. Doing as you’re told in one appointment is the only route to ensuring the next.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe civil servants’ power lay in the work of the Nolan Committee which, in the mid-1990s, came up with recommendations to remove patronage from political hands and create an independent merit-based system. Instead, it placed enormous discretion in the hands of civil servants, covered by a façade of fair process. And so it has remained.

Most public appointments are non-controversial but some are extremely important to the way organisations function. For example, it was a crucial factor that there was not a single island resident on the board, far less as the chair, of either Caledonian MacBrayne or CMAL, the procurement quango, while the ferry scandal was evolving over the past decade.

That was not by inadvertence. There is a very entrenched hostility to the idea of islanders being on these boards because they might represent the view of, well, islanders rather than government policy. A chairman in Denmark was a safer bet. Ministers point to the “independent” appointments process – but any process is only as fair as the people running it.

Fighting your corner

But was it not always like this? Well, no actually, it wasn’t. There was a time when heads of quangos like the big development agencies were household names, taking on the Scottish Office when required in order to fight the corner they had been appointed to. Few of them were politically partisan, and therein lay their strength. If ministers didn’t like it, they could sack them – a prospect that would strike dread into today’s professional quangoteers.

The quango I have known best over the decades is Highlands and Islands Enterprise, previously the Highlands and Islands Development Board. It was chaired in the past by some big people with varied hinterlands, directly appointed by the Secretary of State of the day. The shared characteristic which each developed was a loyalty to the organisation and region, stronger than to the government that appointed them. Then I look at last week’s budget from Shona Robison which included a 13 per cent cut to HIE’s budget, meaning a real-terms 40 per cent cut since 2018-19. Where was the resistance?

Any society needs competing points of strength and the dynamic of dissent. What we have seen in Scotland is the relentless promotion of conformity over challenge. When that is applied to councils, quangos, the third sector and every grant-dependent supplicant, it creates something deeply unhealthy.

Respect for challenge to government as a healthy virtue is now a major part of the change Scotland needs. Instead, we have Mr Russell.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.