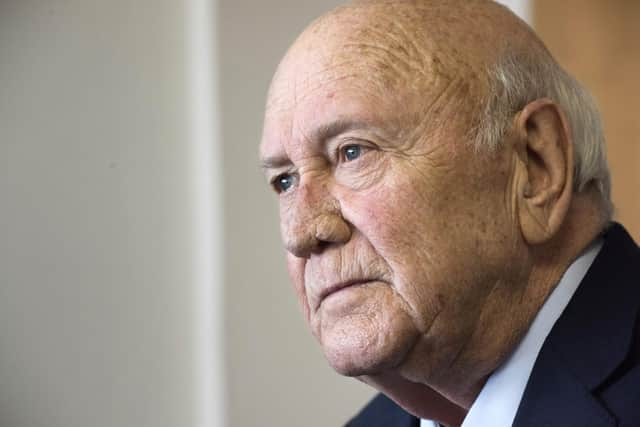

FW de Klerk helped make South Africa and the world a better place by agreeing to end evil apartheid regime – Christine Jardine MP

The message on it isn’t anything particularly personal or special and the handwriting is a little scrawly and elderly looking.

But I kept it there as a reminder that great change can be achieved if you have the courage to think the unthinkable, recognise your own failings, and take that first frightening step out of the darkness.

The signature was FW De Klerk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was not amongst my greatest political heroes, or even the South African I admired the most.

But he was someone whose part in that astonishing February in 1990 when Mandela walked to freedom was as significant as it was controversial.

News of his death this week reminded me of the sheer elation, joy and relief that greeted the news that apartheid, one of the 20th-centuries worst crimes against humanity, was to end.

And not in the bloodbath born of frustration at the brutality and injustice of a heinous regime, which was what many of us had feared would come with its ultimate demise.

But in statement by a white, Afrikaans-speaking, South African president to the legislature and party that had first created and then defended a system reviled across the world.

That is why on a sunny day in Cape Town 24 years later I took the opportunity to shake hands with the man without whom that relatively smooth transition to black majority rule might never have been possible.

His contribution was, of course, recognised in the Nobel Peace Prize he shared with Nelson Mandela, although the two were never close and De Klerk did not share the popular acclaim.

The ANC leader’s own critique of De Klerk was less than gushing and in his autobiography he suggested that the decision to end apartheid was less to do with a moral imperative than what might best serve the long-term interests of the white minority.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCertainly questions over the motivations and moral judgements of the white South African population at that time were an international concern.

Like so many people of my generation, I was torn by the internal conflict between having much loved and missed relatives in Southern Africa and abhorring the regimes under which they lived.

How could they live in those societies? Why could they not see what was obvious to the rest of the world? Even after Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, the campaign to end apartheid seemed, at times, hopeless. There were protests, concerts, embargoes.

I was never prouder of my home city than when Glasgow councillors changed a street name so that the South African Consulate had to acknowledge on all its stationary that its address was 1 Nelson Mandela Place.

We stopped buying South African goods and for more than two decades a sporting embargo provoked controversy.

A young activist called Peter Hain became synonymous with disruption of those white South African sporting tours which did take place.

On De Klerk’s death, the now Lord Hain was amongst those who came forward to recognise his contribution to change.

But the words which will stay with me and provide, I believe, the most fitting end to that politician's story is the video which he recorded shortly before his death.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn a final message to South Africans, and presumably the rest of the world, he repeated his earlier apology for the pain and suffering that had been caused by that most evil, racist of systems.

Even on his death, I am sure the reactions will be diverse and complicated.

There will be those who question whether a death-bed apology and one brave change is really enough to compensate for the years of suffering caused by the regime of which he was an integral part.

Others will point to the courage and conviction it must have taken to change the stance of the party whose ranks he had risen through and which had made him president, only to see him overturn what they had built.

That meeting I had with him in 2004 was the briefest kind possible. Having eschewed a visit to South Africa during white minority rule, I had finally gone with my husband and then ten-year-old daughter to visit relatives in Cape Town.

Leaving our hotel in the shadow of Table Mountain, my cousin confirmed that yes, the elderly man approaching was FW De Klerk.

Throughout my career, I have declined countless opportunities to ask for autographs and selfies with politicians and celebrities, but somehow this was different.

As he reached the door, I stepped forward and mumbled some embarrassed explanation about being able to visit my family now, the significance of his actions in creating change and how important it had been.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI asked if he would mind signing something for me and passed over the piece of paper which came home with me and sat on my workstation.

I have often looked at it and wondered what exactly it was which made me want to speak to him that day.

I think it was that for most of my young life, it had seemed impossible that the ruling National Party could be persuaded to see the inhumanity of their cause and end a regime that I regarded as a moral scar on our world.

All of that ended that glorious day when the entreaty ‘Free Nelson Mandela’ was no longer necessary.

There may always be questions about de Klerk’s motivation but I believe that all politicians want to leave the world a better place.

Perhaps de Klerk at least achieved that for South Africa?

Christine Jardine is the Scottish Liberal Democrat MP for Edinburgh West

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.