Aberdeen University's JM Barrie trigger warning is just infantilising its students – Susan Dalgety

I was puzzled by his question. “On the bookshelf at home,” I said. He smiled again. “It’s just that the themes are a bit…well, adult, but anyway, well done.” As I wandered back to my desk, I wondered what he meant. As I had told him, I had found DH Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers a few weeks previously while hunting for something to read.

As an introverted 12-year-old who read everything, including the cornflakes packet every morning as I ate breakfast, I hadn’t given it a second thought as I opened the paperback and started reading Lawrence’s novel about love, class and the bond between men and their mothers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDid I understand every nuance? Probably not, but enough to be able to summarise it for my monthly book report, or “home reader” as it was dubbed. Was the stultifying tale, written in 1913, about a young man, Paul Morel, and his relationship with his mother Gertrude, too adult for a child? Probably.

But I had been reading “adult” books since I was ten and had not come to any noticeable harm. It was real life that was the cause of my misery. Reading was my solace, whether it was classic literature or crime novels. In rural south-west Scotland in the late 1960s, bookworms like me got their daily fix where they could.

There was no such thing as young adult fiction. Buying books, except at jumble sales, was out of the question. They were simply too expensive, so the fortnightly mobile library was my lifeline. I don’t think I was in a bookshop until I reached university. The school dished out our set texts for our English O grade and Higher. I was sorely tempted to keep the battered copy of Catcher in the Rye I read in fourth year, but guilt made me return it after reading it twice in a fortnight. I have loved American fiction ever since.

Like all good art, the best novels help make sense of the disorder that threatens to engulf most of us. Even pulp fiction is a door to a different world. Books definitely saved me as a child, as did the music of David Bowie that first entered my life shortly after I read Sons and Lovers. And great photography has the power to move me even more than a brilliant painting. I prefer my art steeped in reality, rather than fantasy, which is probably why I was never a big fan of Peter Pan.

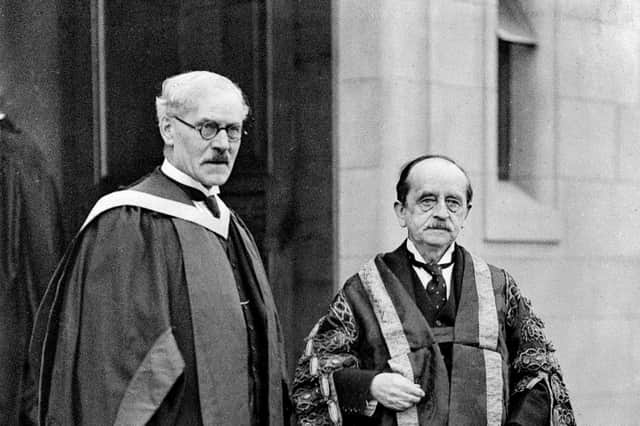

The tale of the boy who didn’t want to grow up has, for better or worse, become part of our cultural DNA. Most people will have never read the play JM Barrie wrote in 1904, or Peter and Wendy, the 1911 novel it inspired, but thanks to the 1953 Disney film and countless pantomimes, most people know the character and his arch-enemy, Captain Hook.

Peter Pan hit the headlines this week when it emerged Aberdeen University had slapped a content warning on a collection of JM Barrie’s plays which includes Peter Pan and Mary Rose, a story about a girl who mysteriously disappears not once but twice. Other classics that have attracted warnings include Treasure Island, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and The Railway Children. It seems that students are given a list of books, plays and films they may find “emotionally challenging” and told to seek help if they feel unable to cope with the feelings the works invoke.

“Our guidelines on content warnings were developed in collaboration with student representatives and we have never had any complaints about them – on the contrary, students have expressed their admiration for our approach,” said a university spokesperson in response to the almost universal derision that greeted the revelation that such stories had effectively been given an X-rating.

And writing in this newspaper, Professor Timothy Baker of Aberdeen University argued that providing students with advance information is a way of “taking them seriously as participants in challenging conversations". “There is no student whose academic performance is improved by having distressing material sprung on them as a surprise,” he said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI pity the poor arts undergraduates of Aberdeen University. Don’t they know that most great art is rooted in misery? Take Maya Angelou’s ground-breaking memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, for example.

It explores the darkest aspects of humanity. She was raped when she was eight years old, a horrifying incident that left her mute. Yet it is a story of liberation and resilience which should be read by every teenager terrified of the world. Far from triggering them, it will fire them up with the knowledge that even the most awful life events can be overcome, that a caged bird can still sing, even when frightened for its very soul.

Professor Baker clearly believes that his university is doing the right thing by its students, protecting their well-being with warnings that they may find some literature distressing. Instead, he and his colleagues are infantilising them.

Good literature is supposed to surprise and challenge the reader, to take them beyond themselves. The best, like Angelou’s work, shows the power of words to heal and inspire. It needs no content warning, no label that may scare off more timid, or lazy, readers.

And the best literature is like life. The reader needs to dive in, immerse herself in the story, even when she knows that there will be difficult chapters or scenes that will make her cry or frighten her. Make her angry even.

Stories, the scary as well as the comforting, are how we come to terms with the best and worst aspects of our humanity. And being surprised by the tough bits, then dealing with them, is how we grow up.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.