Brexit: Why Scotland faces a slow decline – Alistair Heather

At some point soon, we will be stripped of our European citizenship. Our wives, husbands, hated neighbours, loved friends, tolerated colleagues, any and all Europeans that live here will be stripped of their rights and become less than us. Less secure, less valued, less physically safe. Our institutions will be impaired, our horizons narrowed.

Edinburgh will be reduced for the second time in its history. After the loss of the national parliament in 1707, it ceased to be a capital. Within Europe, its light, relit, has burned brightly for 50 years, and the city has taken its place as one of the great capitals. With Brexit this light will dim. Edinburgh will be cast down into parochiality. A secondary city within a secondary region of the UK. The city of the Enlightenment will be in the same all-British bracket as Slough, Norwich, Wolverhampton.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor decades our horizons have been wide open. Paris, Rome, Prague, Helsinki. Scots have found berths in every one of these places, contributing to the community they find themselves in, acting as bees in the cross pollination of good ideas that has been helping the intellectual economy and cultural integration of Europe blossom.

This is Scotland’s right historic place. We are on the edge of Northern Europe. Sutherland, Caithness and much of the Western Isles, not to mention Orkney and Shetland were domains with shared populations and experiences with Iceland, Norway, Greenland. Iceland’s women are 50 per cent descended from Scottish and Irish women.

We are just a short stretch of water from the continent, and in the past those seaways have seemed like motorways. Poland teems with the ancestors of the 40,000 Scots families that flitted across the North Sea in the 1600s, trading the famine raging at home for opportunities abroad. Scottish surnames given Polish inflection over the years include Kietzs (Keiths), Losons, Ramzes and Szynklers. The four-time mayor of Warsaw between 1691 and 1703 Aleksander Czamer was born Alexander Chalmers in Dyce, Aberdeenshire.

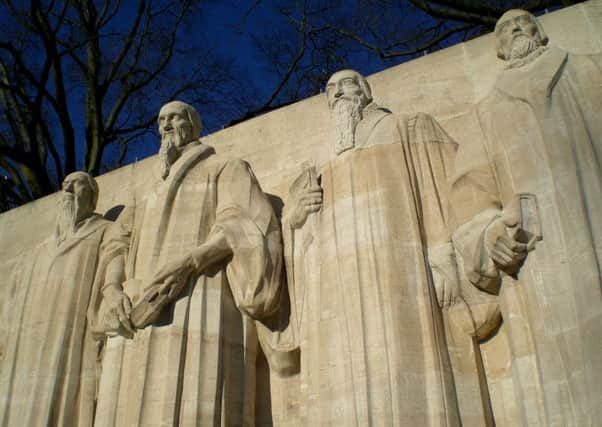

More than genetics, more than common names bind us to our European neighbours. The very words in our mouths indicate our shared past and common present. The Scots language has common words in the Scandinavian language – such as ‘bairn’ for child and ‘braw’ for good – and in Ireland, our near European neighbour, Ulster Scots retains some vibrancy. Our own Scots Gaelic started life as the Ulster dialect of Irish, the shared languages evidence of endless Hiberno-Scottish relations. In Switzerland, I was surprised to come across a 40ft statue of Scotland’s queen-bothering reformer John Knox, towering above a central city park. At the statue’s feet was a massive mosaic of the Lion Rampant, Scotland’s ancient emblem. Behind the statue in the old town is the Kirk of Scotland. Elsewhere in the city, you’ll find the Genevan Gaelic choir meeting, and on other nights the Swiss Scottish Country Dancing Society.

Some might say that these glory days of European influence are behind us. That Europe was our past and Brexit our future. Not so. Scotland is becoming more European as the years pass, not less.

There are many tens of thousands of new Scots who are absolutely European, and no vote will change that. The Polish, Baltic state, Romanian migrants and their children, many Scottish born, who make up chunks of our population are and will remain European. Their next generation will likely be at least bilingual, with one modern European language as a mother tongue. Much as the great Irish migrations have redoubled the connections between Scotland and Ireland, so too will the legacy of the more recent eastern European migrations culturally tether future Scots to those countries.

This is not an article in defence of the EU. This is an article in favour of open borders, of knowledge sharing, and of cooperation. I’m aware that the EU also creates borders and enmity with Russia, with Turkey and others. But saying the EU is too exclusive and so choosing Brexit is like complaining of claustrophobia in a large public park and curing it by upturning a bucket on your head.

Scots are Europeans by language, by history, by ancestry, by geography and by experience. Isolated from Europe, Scotland will be heading for another period of intellectual darkness.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur famous universities are amongst the best in the world. And our population is the second best-educated in Europe, in terms of university degrees per head. This is an enviable position for a small country to be in. And it’s down exclusively to internationalism and tight European connections. Our universities certainly carry out groundbreaking research, but they generally do so with large EU grants, or in conjunction with other universities. They almost always conduct research and education with large staffs of EU nationals, who will soon become legally insecure.

The impact is already being felt. Scottish universities experienced a drop-off in applicants from EU countries. EU students are vital, as, although they are generally fee-free, they have a massive economic impact on the community around the university. They rent expensive flats, spend student loans in shops and bars, and work lower-paid jobs during their studies. When they graduate many stay, making positive contributions to their community and the economy. Those that leave become positive ambassadors for Scottish education internationally.

In what can only be described as an intentional and massive ‘get it right up you, Scotland’, the Home Office has committed to offering EU students three-year visas to study in the UK. Degrees in Scotland take four years. In England, most take three.

Our universities provide superb education to massive numbers of working-class and lower-income Scots. They are one of the key tools in providing social mobility in Scotland. They allow us to mix with European and international students, to form relationships that last lifetimes, to engage in projects and enterprises across a infinite number of fields. They are Scotland’s window to the world. They are a window through which Scots can reach out and have a positive impact internationally. Brexit will do much to close that window.

Holyrood has been damaged too. How can we look to the parliament in Edinburgh as anything other than a diddy wee ‘pretendy’ parliament, when it can do nothing to either prevent Brexit or gain Scotland’s independence? There’s been a pro-European, pro-independence majority in there for umpteen years, and yet we are set to lose our European citizenship thanks to an English majority in its favour.

All this talk of cliff edges probably isn’t correct. Instead what we’ll experience will be long, slow subsidence. A steady trickling away of blood, of energy, of vibrancy. We are, right now, an integrated European partner on the cusp of independence. A new European nation right in the crucible of formation, with all the promise that entails.

If Brexit drags Scotland with it, it will take us a very, very long time to get back to the position we are currently in today.

Alistair Heather is a writer and presenter and is on Twitter @Historic_Ally