Scotland's land: How rocketing prices and a dash for green climate fixes is driving concentrated ownership problem and freezing out local communities

Scotland is up for sale to the “highest bidder” with “radical” reform required to break the centuries-old system of concentrated private land ownership in Scotland, it has been claimed.

Community Land Scotland (CLS), which supports community land ownership, has spoken out as the Scottish Government prepares to publish a new Land Reform Bill. There are concerns the new legislation will not go far enough in tackling inequalities in ownership while leaving communities with little control over the way local land is managed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland has seen a rapid rise in land transactions as investors and corporate bodies rush to buy land for tree planting and peatland restoration, with ‘natural capital’ schemes allowing landowners to generate lucrative carbon credits that can offset their organisation’s own carbon emissions or sell them on carbon markets for increasing sums.

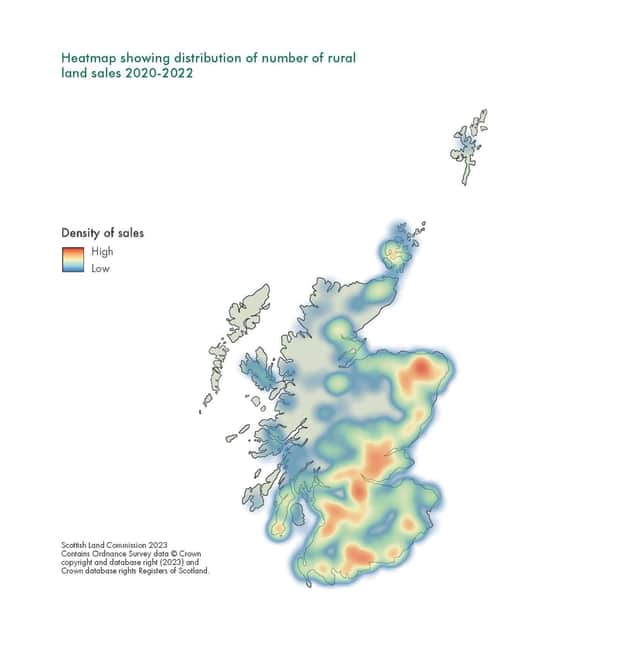

The phenomenon has been dubbed a “carbonanza” by CLS, with latest figures showing £1.3 billion-worth of land transactions were completed in Scotland between 2020 and 2022, and values of estates, forestry and estate heating up during the three-year period, particularly in the north-east and south-west of Scotland.

Fundamental concerns remain that communities and individuals remain frozen out of the opportunities presented by natural capital schemes.

In Dumfries and Galloway, the price of forestry has risen 450 per cent in some cases. Further issues surround land in Scotland being bought simply as a financial asset.

Josh Doble, policy manager at CLS, said Scotland land’s market remains almost completely unregulated, with no rules on how much can be bought up or by whom, with land viewed as a safe investment that holds its value.

Mr Doble said: “It’s completely open to the highest bidder. Scotland is attractive to wealthy investors because of that lack of regulation and because there is a secure economic and political system in Scotland and the likely medium-term impacts of climate change are not as severe here as in other places.

“Another other key issue is that land prices are soaring, and have been for a while.

“That’s being driven by investor interest in land due to the lack of regulation and also by the large profits and tax breaks you get from forestry, and because of the prospect of carbon sequestration and natural capital projects. Land prices are going through the roof."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

The Scottish Government’s Land Reform Bill is due to be published imminently, with measures expected to include the introduction of a ‘public interest’ test for transfers of large-scale landholdings – proposed initially at 3,000 hectares – with an aim to introduce a pre-emption in favour of community buyout, where appropriate to do so.

Under proposals, landowners would be compelled to publish management plans, which could include detail relating to community engagement and nature restoration projects. It would also place a legal duty on landowners to comply with the Land Rights and Responsibility Statement, which sets out the need for transparency and a high standard of land ownership linked to environmental, economic and cultural benefits.

CLS – and a number of other bodies and politicians – have called for the public interest test to be applied to land sales of 500 hectares. In addition, it wants landownership limited to that size, with any larger holding needing to demonstrate it serves the public interest.

The organisation said it was concerned that, as it stands, the proposed legislation would fail to deliver on the Government’s aim of “a more diverse pattern of land ownership and tenure and that a significantly higher proportion of land should be owned in Scotland by the communities that live and work there”.

Meanwhile, Scottish Land & Estates (SLE), a body which represents Scotland’s landowners, released analysis it commissioned from BiGGAR Economics. The analysis concludes that large-scale land use and ownership needed to be “embraced by government” to meet targets on rural housing, nature and the environment, with “fragmentation” putting the national vision at risk.

The report said peatland restoration needed to increase by over 300 per cent to reach the Scottish Government’s target of 250,000 hectares of restored peatland by 2030, with rural estates accounting for 57 per cent of restoration since 2013.

While the Scottish Government aims to create enough woodland to cover 21 per cent of Scotland’s total area by 2032, the report said it would take almost 48 years – at the current rate of delivery – to reach this target through only small-scale projects of up to 50 hectares.

Sarah-Jane Laing, chief executive of SLE, said: “Ambitious targets have been set by the Scottish Government across net zero, nature and housing and, if there is any hope of these being met, working at scale is the best way to achieve that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

“It is clear from the research that fragmentation of land use ownership will both reduce the pace of delivery and also the level of investment available.

"Delivery of homes by large landowners, and large-scale projects for nature involving single or fewer landowners, tend to be less complex, contain fewer risks and are quicker to deliver than projects with governance agreements between multiple parties.

“Landowners of all types and sizes are making a significant contribution to Scotland’s well-being but if the government wants to meet its targets then it should be looking to retain or even increase scale.

"Forthcoming land reform proposals are likely to put delivery and investment at risk.”

Scotland has a total land area of nearly eight million hectares, but its ownership is considered the most unequal in the western world, with the majority of ground held in a small number of hands. This uniquely concentrated pattern has continued virtually unchanged for the past 500 years, and has even increased in the past 50.

Around 12.5 per cent of the country is publicly owned, but it is thought just 430 or so landowners – less than 0.01 per cent of the population – control half of all private land outside the main towns and cities. Research suggests the situation creates an imbalance of power that can lead to “localised monopolies”, with an excessive impact on an area and its inhabitants.

Successive Scottish governments have been working to modernise the system over the past 20 years, pledging to diversify ownership and clarify who large parts of the country actually belong to.

Danish clothing tycoon, Anders Holch Povlsen, is now Scotland’s single largest private landowner after buying up a vast swathe of land covering around 90,000 hectares across 13 estates in Sutherland and the Cairngorms. His plans centre around rewilding and nature restoration on a grand scale, with a number of high-end hospitality businesses now also operating on his land.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis registered carbon credit schemes for tree planting and peat restoration amount to one of the largest combined projects in the UK.

The Scottish Land Commission (SLC) was established by ministers following the Land Reform Act 2016 to drive a programme of reform for both urban and rural areas and create a system where land is owned and used in a fair, responsible and productive way.

It warned ultra-concentrated ownership is damaging life in some places, with a small number of big players able to exert high levels of control over basic needs.

SLC chief executive Hamish Trench said: “I think our own investigation into the scale and concentration of land ownership shows that really the key issue here is about power over decision-making, about power over decisions that affect the communities in terms of the economy and social well-being.

“Really the core issue we found is that where you have a very concentrated pattern of ownership it inevitably brings the risk of localised monopoly.”

This lack of say over how land is managed means local people can miss out on potential benefits, and problems such as rural depopulation can be exacerbated.

A revamp of the taxation system has also been suggested.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.