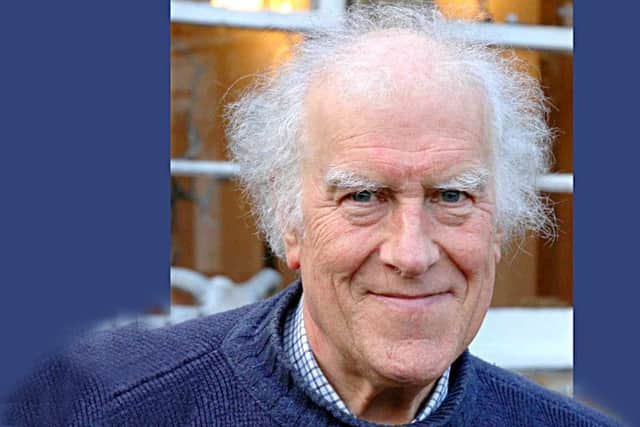

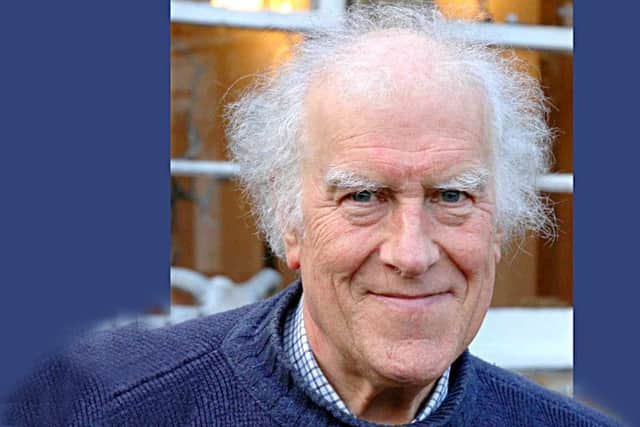

Professor Tony Trewavas: Environmentalists have it all wrong '“ technology will solve our problems

Stellenberger and Nordaus state that modern environmentalism must die so that something new can live; a positive inspiring vision of the future in contrast to the pessimistic messages and narrow technical solutions previously proposed. The gauntlet was thrown down in 2015 with the publication of the Ecomodernist Manifesto.

Humanity, environmentalism assumes, simply depends on nature’s flows and resources that are in fixed or limited supply. If that assumption were true, then, logically, civilisation would eventually collapse as population and resource exploitation continued to rise. If it hasn’t happened now, it is said, it is just around the corner. This fearful Malthusian view has been debunked so many times, it should have been expunged many decades back.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the recent UN Human Development Report indicates that life expectancy, health, education and income found in at least 40 countries gained much more than had seemed possible in 1990.

This environmental paradox is solved once it is understood that economic growth is partially or totally decoupled from the use of resources by technology. Over several centuries, knowledge of genetics and agricultural engineering has seen total food production far surpass the seven-fold increase in world population.

The recent green revolution has saved an estimated one billion people from starvation and intensification will increase yields further, eventually releasing land back to the natural world. Reforesting has occurred in parts of the US as unprofitable farms have been abandoned; synthetic fibres have seen another 60 million hectares of sheep farms abandoned to nature as wool prices slumped.

There is some environmentalist opposition to further agricultural yield development in the belief that small farms of the past existed in a rural arcadia. Such attitudes, with their indifference to the one billion who don’t get sufficient to eat, can only be regarded as inhumane.

Food production should be as efficient as possible so that the goal, half of all useable land returned to nature can finally be achieved. Many of the extra four billion people reckoned to be present by 2070 will not want the abstemious path proselytised by Gandhi but rightly want the wealth, health and creative long life currently experienced in the West.

The choice will not be whether to constrain our growth, development and aspirations or die, but whether we will continue to innovate and accelerate technological progress in order to thrive. Malthusian outcomes are not impossible, but neither are they inevitable.

Shellenberger and Nordhaus objected to the Kyoto treaty because it talked about shared sacrifice rather than shared innovation. Technology does not stand still. Most innovations have initial problems but history teaches that failings act as incentives to improve. Progressive change becomes inevitable.

Compare transport, heating, energy generation, medicine and communication with a century ago. The present may have some problems but a century back it was much worse. And 100 years hence, technology will be better in every area. Matter, energy and ingenuity are critical; the solution to the ecological problems caused by modernity, technology and progress are actually more and better technologies, increased modernity and increased progress.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor many centuries, mankind has used ever more energy and the sources used, from wood to coal to gas to nuclear have become increasingly energy dense. By 2070, hopefully most of the expected 11 billion people will live in megacities occupying, at best, 5 per cent of the land. They will require energy sources that are cheap, clean, dense, abundant and reliable. Of those currently available, only nuclear is practicable. Some environmentalists oppose nuclear energy, mistakenly thinking that wind farms, solar energy and organic farms are all the future needs. Thoughtful environmentalists who support nuclear energy know that these space-hungry renewable sources can only provide enormous amounts of electricity on demand if coupled with humungous energy storage capabilities. This would make them prohibitively expensive.

It may be that, in a remote future, such storage is developed but by that time, nuclear, like all technologies, would have moved on to fail-safe, liquid salt or fast breeder reactors and waste-free energy production.

Decoupling mankind’s material needs from nature, creating an enduring commitment to preserve wilderness and beautiful landscapes requires a deeper emotional connection to them, clearly absent in this present government.

We inhabit a world so profoundly changed, that the assumptions on which modern environmentalism was founded 60 years ago no longer hold. Modern environmentalism is dying of old age.

Emeritus Professor Tony Trewavas FRS is chairman of Scientific Alliance Scotland.