Insight: The jury's still out on '˜not proven' verdict

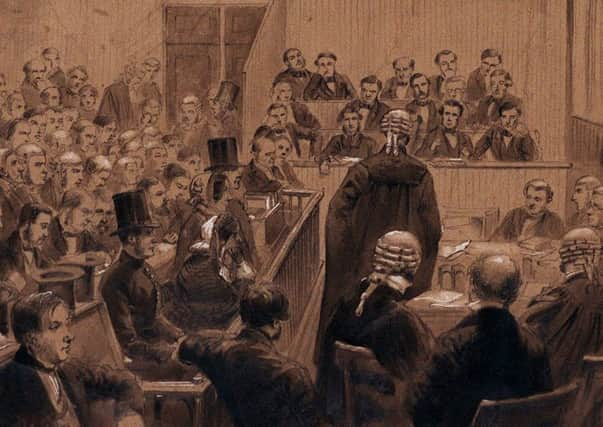

The evidence against Monson was circumstantial, yet damning. He was a man with a shady financial background. Six days before his death, Hambrough had taken out two life insurance policies in the name of Monson’s wife. Less than 24 hours before his death, he had almost drowned on a fishing expedition with Monson after the boat – into which a hole had been drilled – sank. Add to this the implausibility of Monson’s version of events – that Hambrough had accidentally shot himself while climbing a fence – and the mysterious disappearance of the only witness, Monson’s friend Edward Scott, and you might think he was bang to rights.

But Monson’s advocate, John Comrie Thomson, one of the finest lawyers of his day, sowed doubt in the minds of the jurors; he said it was impossible for Monson to have benefited from the insurance policy because Hambrough was a minor and the funds would have been passed straight to his father, and he pointed to a lack of physical evidence. In the end, the jury found the charge “not proven” and so – to the horror of Hambrough’s friends – he walked free.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland’s not proven verdict – the “bastard verdict” as Sir Walter Scott called it – has been causing controversy for hundreds of years. Where most jurisdictions, including England, have just two possible verdicts – guilty or not guilty – jurors here are offered a third: “not proven”. This verdict is often perceived as a compromise, useful when the evidence against the defendant is strong enough to lead them to suspect guilt, but not strong enough to convince them “beyond all reasonable doubt” – the test required for a conviction.

The three-verdict system, however, has a key flaw; lawyers and judges struggle to explain the difference between not guilty and not proven largely because, in practical terms, there isn’t one. With either verdict, the accused is cleared and cannot be retried on the same charge unless important new evidence is uncovered. Such is the lack of clarity over the not proven verdict, even within legal circles, that judges are discouraged from giving jurors any guidance over how it should be used, with the appeal courts occasionally slapping down those who do return it. It is hardly surprising then that what little research has been carried out suggests jurors are often confused, while the general public often interpret it as meaning “not guilty and don’t do it again”.

Criminal defence lawyers tend to be fans of the not proven verdict, perhaps because they believe it weights the system in their clients’ favour. In public, they insist it reduces the chances of a miscarriage of justice because juries who believe a defendant has committed the crime but don’t feel they can convict have a way to acquit without declaring the defendant innocent. In other words, in borderline cases, it allows them to err on the side of an acquittal. On the other hand, is it fair that those cleared of a crime should continue to carry the stigma of guilt? Monson, for example, was always regarded as “having got off” with the murder; years later, he sued Madame Tussauds for displaying a waxwork of him, a case which established the principle of defamation by innuendo.

The campaign to scrap the not proven verdict started to gather momentum in the 1990s when three men – all accused of murder and all represented by Donald Findlay QC – were acquitted on that basis. Since then advice has been sought and consultations have been launched. Yet, last week the latest attempt to have the not proven verdict abolished was once again scuppered. MSPs on the Justice Committee who were considering Labour MSP Michael McMahon’s Criminal Verdicts Bill agreed it “may be living on borrowed time”, but could not accept the accompanying proposal to increase the majority required for a conviction from 8/7 to 10/5. The MSPs called for “further research into jury reasoning and decision-making to ensure that changes to several unique aspects of the Scottish jury system are only made on a fully informed basis”. In other words, much like the decision over scrapping the requirement for corroboration, the not proven verdict has been kicked into the long grass.

Meanwhile, other jurisdictions have toyed with the possibility of introducing the verdict. In the United States, Senator Arlen Specter tried unsuccessfully to vote not proven on the two articles of impeachment of Bill Clinton, while campaigners called for it to be introduced after the OJ Simpson trial because they felt the not guilty verdict was not an accurate reflection of the jury’s position.

So what is the truth about this contentious verdict? Is it, as its defenders claim, a safeguard against wrongful conviction or a red herring that serves only to distract those tasked with assessing the evidence? And do we cling to it out of a faith in its efficacy or a perverse pride in our “unique” Scottish system?

If the latter is true, then we are probably kidding ourselves. The not proven verdict was not introduced because great legal minds agreed it was the most likely means of ensuring justice; rather, it evolved from a mixture of circumstance and inertia. James Chalmers, professor of law at Glasgow University, explains that, at one time, juries in Scotland were asked to determine factual issues one by one as “proven” or “not proven”, with the judge left to determine whether there was enough evidence overall to establish guilt. Later we went back to guilty and not guilty verdicts, but the “not proven” verdict was never formally abolished and so it lived on. “We got this system pretty much by accident,” says Chalmers.

Since then, many high-profile defendants, including William Burke’s common-law wife, Helen McDougal, and Madeleine Smith, a Glasgow socialite accused of murdering her lover, have arguably retained their freedom as a result of the “not proven” verdict.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe three cases that raised concern in the 1990s were the murders of taxi driver Raymond Mullan, budding football star Colin McCaskie and drama student Amanda Duffy. In the first case, the jury came to its unanimous “not proven” verdict after hearing how Mullan had jumped into the back of his cab and impaled himself on the hunting knife of the accused, 19-year-old David Anderson.

Later, some of the families affected launched a campaign to have the verdict abolished. Findlay spoke up in its defence. “Maybe my client did commit the crime and my expertise got him acquitted, but my real concern is that maybe he didn’t do it and might’ve gone to jail anyway,” he said of one case. “Better that nine guilty men go free than one innocent man go to jail.”

In the past few years, the ante has been upped as McMahon brought his private members bill, but he has been fighting an uphill battle, with some lawyers and politicians fearful that changing one element of the system in isolation, or even several elements together, might have unforeseen consequences.

One of the problems decision-makers face is the lack of evidence on the pros and cons of the not proven verdict. You can look at the statistics and discover that, in 2014, it was used in 1 per cent of trials and 17 per cent of acquittals, but what does that tell you about its value or how jurors would behave if it were removed? Some people have pointed out that it is common in rape cases (20 per cent of trials and 35 per cent of acquittals) and Rape Crisis Scotland is concerned that it contributes to guilty men walking free. But, Chalmers, who led the academic experts’ group involved in Lord Bonomy’s Post-Corroboration Safeguards Review, is unconvinced. “Rape juries are more likely to acquit [because of the difficulty of gathering evidence and the high stakes]. But when they do, it splits [between not guilty and not proven] in much the same way as, for example, murder.”

The best way to test the potential impact of a shift from three to two verdicts would be to question juries on their decision-making process, but interviewing jurors about their deliberations is prohibited in the UK under Section 8 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981 and the Ministry of Justice last year rejected calls to amend the act. The need for more research has been accepted by the Scottish Government, but it has yet to commission it and it is not clear how it will be conducted.

Two existing studies, carried out in 2008 and involving “mock jurors”, offer some limited insight. In the first, the mock jurors were provided with a summary of a real-life sexual assault trial and the written jury directions. Some were given the option of guilty and not guilty verdicts and some of guilty, not guilty and not proven. The researchers found the acquittal rate was slightly higher where three verdicts rather than two were available (49 per cent as opposed to 39 per cent). Worryingly, 35 per cent of the three-verdict jurors believed a not proven verdict allowed a retrial at a later date, despite the written directions explicitly stating that it did not.

In Study 2, the mock jurors were provided with the details of a (non-sexual) assault trial and jury directions, but this time three different versions of the summary were used, with the strength of the prosecution evidence varying (weak, moderate and strong). Jurors were randomly assigned to consider one particular version of the summary on the basis of either two or three verdicts .

Overall, the conviction rate in Study 2 was higher where two verdicts rather than three were available (35 per cent rather than 22 per cent). But further analysis showed this association between the verdict options available and the decisions reached was confined to those jurors who had been given the “moderately strong ” version of the case.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his report to the Post-Corroboration Safeguards Review, Chalmers suggested a couple of tentative conclusions could be drawn from this research:

» Jurors do not use the not proven verdict in the manner which the structure of the three verdicts available to Scottish jurors suggests that they, in theory, should and

» The not proven verdict could help to prevent wrongful convictions, because it was in the cases of “moderately strong” evidence – those where most caution would be required – that it appeared to be particularly attractive to jurors.

The research also suggested the not proven verdict might inhibit thorough deliberation as discussions tended to dry up once the possibility of returning it had been mooted.

Chalmers believes the not proven verdict should go. “There is no point at all in having two verdicts which have exactly the same effect if we can’t explain what the difference is,” he says. But he is not convinced more research will help politicians make more informed decisions, as the most it could do would be to confirm or overturn the results of the 2008 experiment. “You might learn that the original research was wrong [about a rise in convictions without not proven] in which case it’s easy, you can get rid of the not proven verdict, because it’s doing nothing. Or – more likely – you will find it does make some sort of difference, but you will have no way of judging if that difference is good or bad.”

The biggest obstacle campaigners face is that there is no pressure for change within the justiciary because – however, extraneous it seems – the not proven verdict is not perceived as causing a serious problem.

“That’s probably right,” says Chalmers. “Outside the occasional high-profile case, the not proven verdict isn’t causing a problem and there’s always this terrible fear of unforeseen consequences if you get rid of it because our bigger juries and different rules on majorities mean you cannot compare it with what happens in England. All this makes it easier to be conservative and just leave things as they are.”

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1