Insight: Education in racism – or just a seven-day sensation?

The week was not without its flickers of hope – Floyd’s brother Terrence speaking out against violence; the donations that came flooding into the Minnesota Freedom Fund; the articulate expressions of anger from many in the Black Lives Matter movement; the white protesters using their privilege to “shield” African Americans.

But they were outweighed by ignominy which reached its zenith when 57 Buffalo officers resigned in support of two colleagues fired for pushing a 75-year-old man to the ground. The man was ignored as he lay bleeding on the ground. As our Twitter feeds filled up with this and other footage, it was no longer possible to ignore the fact that the US has made no effort to confront, atone for, or expunge its original sin, the stain of which was spreading out across the map.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNor could the UK regard events across the Atlantic with complacency. Here, the pandemic was the looking glass reflecting back decades of entrenched discrimination. It is a source of terrible fascination, how the virus has exposed our racial faultlines: the way black and other ethnic communities are disproportionately likely to be poor, to live in inadequate housing and to have public-facing jobs, and are therefore more likely to die from Covid-19.

Yet, here too, there is an institutional unwillingness to confront the problem. Indeed the government delayed publication of the Public Health England report which revealed the disparity because it didn’t want it to emerge against the backdrop of anger over Floyd’s killing. Just as it does not wish to acknowledge that the UK is no stranger to the use of excessive force against black prisoners, or that the Crown Prosecution Service regularly charges those who spit at white police officers, while refusing to take action against the man who spat at station worker Belly Mujinga (Mujinga went on to die of Covid-19).

A confluence of stresses – the pandemic, increased unemployment (particularly among African Americans), an increasingly vocal and authoritarian government – produced the protests (and outbreaks of violence and looting) alongside a sudden outpouring of expressions of solidarity from activists, celebrities and politicians. #BlackoutTuesday led thousands to post black squares on their social media account so as to free up time for them to educate themselves on racism.

There was plenty to ponder. Both the events themselves and the responses to them have raised a series of political and ethical questions, the most obvious being: Whither Trump’s America?

Another is the Catch 22 that exists around graphic footage of assaults on black men and women. The video of Floyd’s killing – which shows him losing consciousness as an officer keeps his knee on his neck for close to nine minutes – serves an important function; it demonstrates the scale of the force used and prevents officers from suggesting he was resisting arrest. But the fact his suffering – and that of others – is served up for public consumption further dehumanises those involved.

“There are so many images it’s hard to keep your sanity sometimes,” says Edinburgh-based French journalist Assa Samaké-Roman. “I sort of understand it, but then I think: ‘Do you really need to see those images to believe there is so much violence against black people?’ I was reading an article the other day that pointed out it would be ludicrous to suggest child services would need to produce images of child molestation for people to be able to accept there is violence and sexual violence against children. But somehow, when it comes to police violence, especially against black people, unless someone is filming it and documenting it no-one will be held accountable.”

There has been much debate, too, over the widespread gestures of solidarity. To what extent were last week’s shows of solidarity genuine and to what extent performative? How meaningful is to take a knee or to black out your Twitter profile in a world where racism is systemic?

For some companies such as L’Oréal – which two years ago sacked trans black model Munroe Bergdorf for talking about white privilege – a public statement in support of #BlackLivesMatter seems like self-serving sanctimony. Other gestures came across as well-intentioned but superficial.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It feels like everyone is suddenly very concerned about racism now, it’s a trend and fashionable, and they can gain social points to post this black square,” says Samaké-Roman, “but there is no call to action, no call for change, for education, nothing.”

One need only think of the editors of most of Wednesday’s newspapers choosing to put a photograph of Madeleine McCann on their front page instead of Star Wars actor John Boyega at a protest to understand her reservations.

“I would like to think that for most people this is the beginning of a journey; that they will try to learn more about racism, but I doubt it,” she says. “I think much of it is virtue-signalling that lasts a day and then everyone goes back to their normal lives.”

In the US, the death of George Floyd, and Trump’s response to it, has provoked the most serious civil unrest since the 1992 Los Angeles riots that followed the acquittal of four police officers who beat Rodney King.

Those riots did nothing to stem police brutality, which has been a constant of modern-day America, but never before has a president so flagrantly attempted to turn the killing of a black man to his advantage, or set out to divide rather than unify in order to justify his authoritarianism and to bolster his position for a forthcoming election.

Trump’s dogwhistle tweets and speeches – which play so obviously to his white supremacist/Evangelical/National Rifle Association bases – horrified not only liberals but veteran Republicans and ex-allies such as James Mattis, who called him a threat to the constitution.

This threat was visible in the casual violence of police officers, emboldened by his support; in his references to the Second Amendment; in his tear gassing of people in Lafayette Square so he could pose with a Bible for a photo outside St John’s Church, apparently oblivious to the fact that the first act served only to underline the cynicism of the second.

On the night of Trump’s election in November 2016, journalist and political commentator Peter Geoghegan found himself on Fifth Avenue talking to a group of pro-Trump Hasidic Jews, while, on the other side of the street, a group of young men in MAGA caps were waving the American flag and aggressively shouting “America First”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I asked the Jewish people, ‘Do you not worry about where America is going?’” Geoghegan tells me. “They answered, ‘No, we don’t believe this is what Trump stands for.’

“The thing that struck me last week was that the idea that the people in MAGA hats and the people in Charlottesville don’t represent Donald Trump has become harder and harder to sustain.”

When Geoghegan filed his election night piece, the word “fascism” was edited out of his copy. “In the wake of the election, it became a liberal-bashing thing – ‘Oh, yes, you think Trump is a fascist’ – and that led to a lot of obfuscation. I think we were all in denial, but last week I felt like it now had become impossible to argue against that level of authoritarianism,” he says.

Geoghegan writes about Trump in a chapter of his forthcoming book Democracy For Sale: Dark Money And Dirty Politics. He says those who have not been following the US closely don’t realise the extent to which the established norms and procedures of democracy have been undermined.

“American presidents do have a huge amount of control, but what we are seeing with Trump is what happens if someone who doesn’t care about norms and traditions gets into power and can and will do anything they want,” he says.

Geoghegan says what Trump is doing now is straight from the fascist playbook. “He is imbuing himself with the innate will of the people; he believes he represents the people, he is the protector of the people – but for that to work he also needs an enemy,” he says.

Trump saw civil unrest in the wake of Floyd’s killing as an opportunity to construct one. “It’s been interesting to see him represent peaceful protesters as violent Antifa – and to promote this idea of ‘outsiders’. What does he mean by outsiders? There is no suggestion they are not American, nor is there the suggestion of a huge amount of co-ordination.”

Upping the ante, he said he planned to designate Antifa as a terrorist organisation, a move some believe would be unconstitutional. “He doesn’t care that this is not possible because it serves the rhetorical purpose of creating an enemy for his project,” Geoghegan says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTrump believed the chaos he had created would allow him to seize more control. According to Geoghegan, he wanted to say: “Look at what carnage democracy and weak governors have wrought – I will restore order by bringing in the National Guard.” But his tactics appear to have backfired. The curfews appear to be stopping the looting, while the protests are continuing peacefully. “That really undermines the story he is trying to tell,” Geoghegan says.

Phillips O’Brien, professor of strategic studies at St Andrews University’s department of international relations, points out that, far from enjoying a bounce, Trump’s approval rating has dipped. And a recent CNN poll of polls found 51 per cent of registered voters backed former vice-president Joe Biden with only 41 per cent supporting Trump.

“I think he made the calculation that these riots would be good for him,” O’Brien says. “He thought he could come out strong on law and order, as a defender of property, but what seems to have happened is that most Americans are tired of constant confrontation.”

There are still five months to go before the election; having watched Trump in action, some fear he will try to cling on to power at all costs.

“I think there are two big questions,” Geoghegan says. “One is voter suppression. We have already witnessed his attempt to prevent postal voting – the Republican machine has an incredible capacity to disenfranchise electors.

“The second question is: does he accept defeat if it comes? He spent months in the run-up to 2016 election delegitimising the result and he will delegitimise the hell out of this one too. It’s a win-win for him because if he is elected, it doesn’t matter he delegitimised it, and if he loses – well, the election has been stolen. This is what is so terrifying about where we are now. “

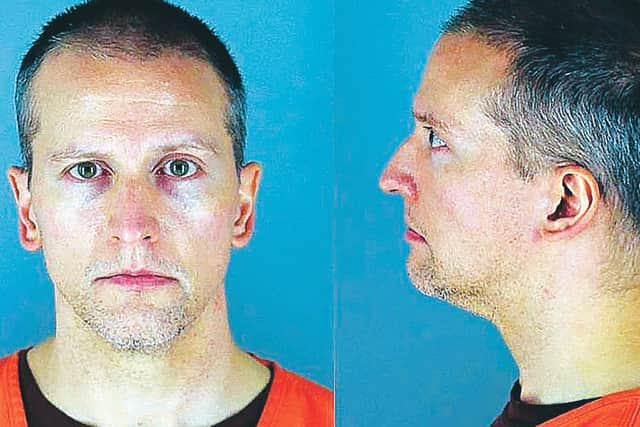

Though #BlackLivesMatter is clearly making a difference – the protests have resulted in all four officers at the scene being charged in connection with Floyd’s death, and the charges against senior officer Derek Chauvin being raised from third degree murder and manslaughter to second degree murder – it is too soon to say whether the events of last week will have an enduring impact on race relations.

“If you lived during the Rodney King riots, everyone said, ‘This is a tipping point,’ but the basic relationship between the races didn’t change much,” O’Brien says. “In the short term, the surprising thing is the rioting hasn’t caused middle class white America to be more supportive of the president. This might show an evolution in assumptions, but we will have to see.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat is undeniable is that – despite the fact we are in the middle of a global pandemic – racism has been pushed centre stage. It has been surreal to see protesters wearing face masks, and the scenes of unfettered brutality on the part of some police officers have been tough to endure.

There is an irony, here, for people of colour, who did not require footage of Floyd’s death to appreciate the extent of racism in the US and elsewhere, and who are slightly bemused by the apparent discovery that it exists.

“It’s not new to us, but I am glad it’s gone mainstream, that there are discussions, and people are realising how unfair and unequal our world is,” Samaké-Roman says. “I am glad white people are learning what black and brown people already knew: that black people are more affected by austerity, and some illnesses and epidemics; that police violence is more targeted against non-white people; that in the US you are three times more likely to be arrested as a black person than as a white person.”

At the same time, the journalist says it is easier to denounce racism that is happening on the other side of the Atlantic than it is to denounce racism on our own doorsteps.

“I think some people think it is all about this poor man who was killed in the US, yet just two days ago tens of thousands of people in Paris were protesting over Adama Traoré, who died while being arrested four years ago and we are still waiting for answers; and in Scotland, we have Sheku Bayoh, so I think it’s hard for some people to recognise the racism that is happening in their own country.”

Samaké-Roman is also perturbed by the inequality in the response to the killings: the names of those victims of police violence that come to mind most readily: Rodney King, Freddie Gray, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice have one thing in common – they are all male.

It took Floyd’s death before the killing of Broenna Taylor – shot dead by police who raided her home in March – made international headlines. Friday would have been her 27th birthday. No police officers have been arrested in connection with her death.

“I doubt most people could say the names of three black women who have been killed in the US in recent years,” Samaké-Roman says. “The plight of black men is real, but so too is the plight of black women.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd yet – for all the cackhandedness – there does seem to be a groundswell of desire to learn and change. So what can white people do to be better allies?

“To me, it is a lot about not taking up space for yourself, “ Samaké-Roman says. “For example, I see a lot of white people on Instagram and they mean well. They say, ‘I thought a lot, I did some reading, I have listened to podcasts’, and I am thinking, ‘This is fine – but what are you expecting from that? Are you really making space for other voices to be heard? Or are you projecting the light on yourself. Are you asking for validation or absolution and forgiveness from the very people who are experiencing the thing you are denouncing, and who want to be heard.’

“I am uncomfortable with that, and yet I think it is better than nothing. I don’t want to reject anyone, but at the same time I would ask people to pay attention to what they are trying to achieve. For me, it is important the work of those who have first-hand experience of police brutality is highlighted. It is important to educate yourself and make way for those voices.”