Batman: Caped icon, masked myth

Even if you’ve never read a Batman comic or seen a single TV episode, even if you’ve managed to avoid all the films from 1966 to 2012 and games ranging from Arkham Asylum to Lego Batman, the chances are you know what I mean by “Batman”.

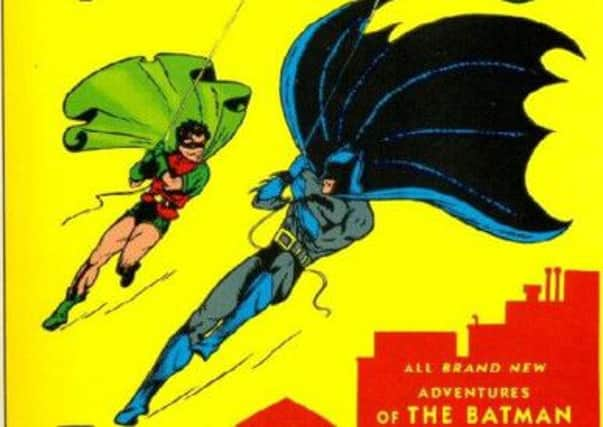

Whether it’s Del Boy or duvets, lollipops or Roger McGough’s poetry, you’ll have come across the Dark Knight. That was why when the Edinburgh International Book Festival asked me to do a talk on “How To Read Batman”, I was delighted. I am, admittedly, a fan. But there are very few modern cultural phenomena that have this kind of traction on our world. How did a character invented in 1939 by Bill Finger and Bob Kane become so iconic, so persistent and so ubiquitous?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBatman is part of the closest thing we have to a modern mythology. By that, I don’t mean the degree of brand recognition the franchise enjoys. Like the stories of Herakles among the Greeks and Romans, or King Arthur among the English, French, Scottish and Welsh, the point of a genuine mythology is how it can be retold, time and again, without losing its core. Herakles in drama by Seneca and comedy by Aristophanes is a distinctly different individual, but immediately recognisable. Likewise, Batman is the same and different whether we’re talking about Grant Morrison’s version, or Scott Snyder’s, or Doug Moench’s or Frank Miller’s or Bill Finger’s. It’s no surprise that the next DC film features Batman and the only other character with, to my mind, similar traction: Superman. It’s like Class #101 in comparative mythology.

Superman is optimistic and sunny. Although he is actually an alien with god-like powers, he is more human than most of humanity, especially since he was raised by loving parents. Batman is an orphan, with no powers except wealth and determination, who prefers to work in darkness and is perpetually suspicious. Look at any comic – Superman: blue sky. Batman: night sky. Superman’s face is always visible – he puts on glasses to disguise himself as Clark Kent – while Bruce Wayne covers his face to become Batman.

Superman has never quite had the same success in terms of opponents (a problem if you create a character who can do almost anything), which might explain why Batman has fared better at the box office. But looking more closely, there’s another difference. Superman tends to be pitted against figures who typify order, control and success (General Zod, Lex Luthor, Ultra-Humanite). Batman’s “Rogue’s Gallery” are chaotic, confused and carnivalesque. The Joker exemplifies this best, but even a villain as megalomaniac as Ra’s al-Ghul, the eco-terrorist who appeared in Christopher Nolan’s first Batman film, and was originally created by Dennis O’Neil, wants anarchy as a prelude to his plans for world domination. The new Beware the Batman cartoon, set in the character’s early career, pointedly pits him against a white-clad villain called Anarky, created by Scottish writer Alan Grant. It’s like Nietzsche’s distinction between the Apollonian and Dionysian tendencies played out in Technicolor.

Batman is a very modern kind of myth, both vigilante and victim, a powerless hero, a bulwark against darkness who drapes himself in darkness. Each incarnation of the Caped Crusader, the Dark Knight, the World’s Greatest Detective is an attempt to unravel these contradictions. In Neil Gaiman’s brilliant Whatever happened to the Caped Crusader? Bruce Wayne is told: “Do you know the only reward you get for being Batman? You get to be Batman”.

There is a paradox in comics, a kind of narrative suspension. The villain has to be defeated, but cannot be destroyed. The hero must prevail, but the victory is always conditional. Grant Morrison very self-consciously played up this aspect in a scene where the Joker realised that he was always trying to think outside the box, and Batman was always trying to build a bigger box around him. Scott Snyder’s Death Of The Family storyline oozed creepiness by having the Joker declare his love for Batman, as he insisted that his nefarious challenges forced Batman to become better. They have to thrive on each other. As the Joker says in Batman #663: “The real joke is your stubborn, bone deep conviction that somehow, somewhere, all of this makes sense!”

“Reading” a comic means more than scanning the speech balloons. It means understanding how image and text are combined, how perspectives are shifted, how the gap between the panels is the space where the reader’s imagination can flourish. There are very few forms where gritty realism and camp, social commentary and utter fantasy can be combined to such effect. No other form can be so silly and serious at the same time. Reading comics is just like reading great literature: the more you do it, the deeper and more sophisticated the pleasure is.” ■

• Stuart Kelly will be talking about Batman at the Edinburgh International Book Festival’s Reading Workshop tomorrow afternoon