The tiny village that clung on for survival

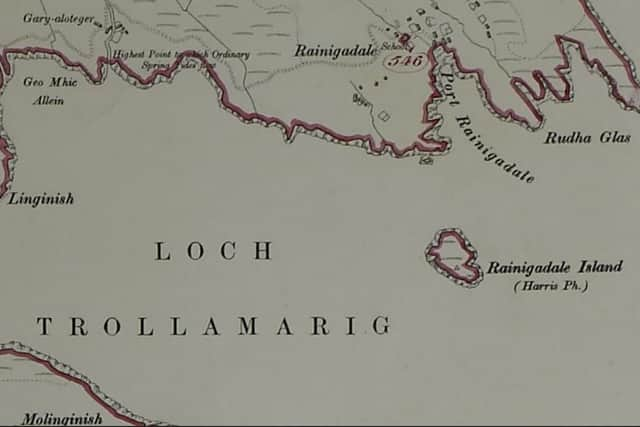

The village was for generations accessible by a narrow, winding four-mile mountain footpath, with the journey described by a local resident as ‘like climbing the Andes’.

Known as ‘Postman’s Path’, the route to Rèinigeadal in the south of the Isle of Harris, which has been described as one of the most remote places in Western Europe, was the

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Adlifeline for the village and the Royal Mail staff who walked it over the years and provided the only means of communication with the outside world.

Accessing Rèinigeadal by sea was scarcely any easier; a fishing boat would have to be chartered in Tarbert, a perilous journey, as the lack of a harbour at Rèinigeadal meant that travellers had to ‘take their life in [their] hands’ having to jump ashore ‘often with someone on your back’.

Unsurprisingly, the survival of these isolated communities had long been the subject of official interest. The fate of villages like Rèinigeadal is inextricably linked to the series of forced eviction of tenant farmers during the Highland Clearances of the 18th and 19th Centuries.

With mass migration following these evictions, the survival of many settlements hung in the balance.

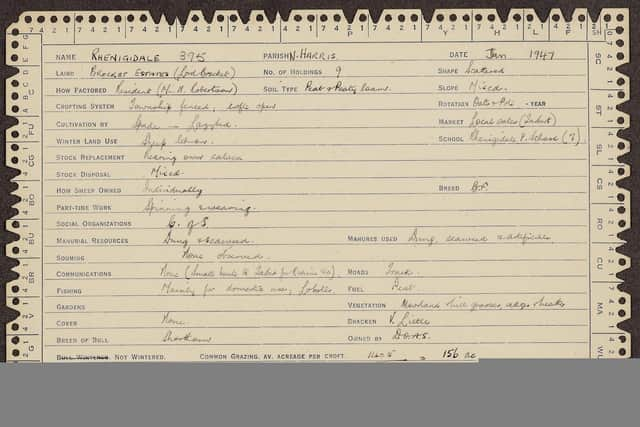

Such was the concern over the dwindling fortunes of these villages, that a “modern-day Domesday” was ordered by the Department of Agriculture for Scotland in 1944. Ecologist

Dr Frank Fraser Darling was tasked with surveying the West Highland and Islands between 1944 and 1951 in a bid to analyse the resources of the natural environment and the social development of this remote part of Scotland. His work gave essential insight into the health of settlements that remained.

At Rèinigeadal in 1947, Dr Darling wrote: “One of the most isoated townships in Harris. No telephone.”

Local occupations and the landscape of Rèinigeadal after World War Two are detailed in Dr Darling’s survey. As you would expect, fishing and small-scale crofting were the main sources of income, with wool spinning generating additional earnings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat is striking is how little the economic makeup of Rèinigeadal had changed from the mid-19th Century with census returns from 1841, 1871 and 1911 showing very similar patterns of employment.

Meanwhile, the Inland Revenue Survey of 1910 - 1915 reveals that the population of Rèinigeadal was by now in serious and long-term decline.

The schoolhouse was built for 22 pupils, but the 1911 census shows that 12 children were attending school and that resident numbers had dwindled to 39. By 1970, there were only two pupils left.

The arrival of electricity in 1981 did little to slow the decline, with only four houses occupied. It was clear that the very existence of the village was under threat.

Kenny MacKay, Rèinigeadal postman and resident, spent nearly two decades arguing that the only way to save his village was for a road to be built between Rèinigeadal and Tarbert.

In late 1979, Western Isles Council agreed to the scheme with a single-track road, linking with the A859, to be built. However, it would be another decade before it was constructed and by the time it opened the population of Rèinigeadal was only 11.

At the time, Moira Laird, Rèinigeadal’s schoolteacher and Kenny MacKay’s fiancé, was “delighted” about the new road but its arrival had profound consequences. Creating a road route to Tarbert meant that the school in Rèinigeadal, with only one pupil on the roll (Ms Laird’s own son Duncan) was deemed unviable and closed. Arrangements were made to bus the boy 12 miles to the nearest school.

The old path to Tarbert is still well-trodden, but now popular with ramblers and mountain bikers. Today, Moira Laird’s old schoolhouse is now self-catering accommodation.