Six abandoned communities of Scotland

We take a look at six communities that have been abandoned in Scotland.

Strathnaver, Sutherland

All that really remains of the townships of Strathnaver, destroyed on order of the Duke of Sutherland in 1814, are a few low dry stane dykes - and several accounts of the barbarous evictions of the tenants who called the Strath home.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe death of 92-year-old Margaret MacKay is perhaps the most haunting. Pleas to the duke’s factor Patrick Sellar to save her went unheeded, with Sellar reportedly saying “Damn her, the old witch. She has lived too long. Let her burn.”

Her house was torched, her neighbours tried to save her and she died five days later.

The accounts of clergyman Donald MacLeod, disregarded during his lifetime but published 70 years later by his son in a book called Memorabilia, are an equally powerful account of the Clearances.

MacLeod said: “I saw the townships set on fire. Grummore with 16 houses and Archmilidh with four. All the houses were burnt with the exception of one. A barn. Few if any of the families knew where to turn their heads or from whom to get their next meal.

“It was sad, the driving away of these people. The terrible remembrance of the “Burnings” of Strathnaver will live as long as a root of the people remains in this country.”

Sellar was later tried in Inverness for crimes including culpable homicide and arson. He was found not guilty and continued to make money from sheep farming in Sutherland for many years.

There are the remains of many abandoned townships throughout the Strath, including Rosal, where the small holding perimeters are still clearly marked. A history trail through Strathnaver charts the area’s Iron Age beginnings - and its brutal 19th century end.

Forvie, Aberdeenshire

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was sand that became the enemy of the villagers of Forvie, around 14 miles north of Aberdeen, who are believed to have abandoned this settlement sometime during the 15th Century.

Stephen Fisk, who has researched abandoned communities across the UK, said the original village was now a few hundred yards inland from the present shoreline, close to a small stream at Rockend.

He said much of the sand now covering Forvie is thought to have arrived after the last glaciers in Scotland melted about 10,000 years ago.

He said: “It would have been transported in huge quantities down the Ythan river and deposited at the mouth of the estuary. Since then there has been an overall movement of the sand in a northerly direction, with the result that quite a lot of it formed the sand dunes at Forvie.”

All that is visible today is the lower part of the walls of Forvie Kirk, built at the highest part of the village which dates from the 1570s

The church was dug out of the sand by local doctor at end of 19th century when the piscina, the basin where the communion vessels are washed, was unearthed.

Later, a full archaeological dig was carried out and a number of square shaped houses were also found.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe site is now Forvie Natural Nature Reserve - home to the fifth largest sand dune system in the UK.

Grahamston, Glasgow

Underneath Central Station in Glasgow lies the remains of a village flattened to make way for the rapidly expanding city.

Grahamston only lasted around 100 years on the west side of the city fringes, with homes and business built to the north side of Argyle Street, then known as Anderstoun Walk.

Grahamston was built shortly after the Forth and Clyde in 1790 and quickly became an important commercial centre close to the ship moorings at The Broomielaw.

Much of its history has been excavated by Glasgow writer Norrie Gilliland.

“It stood literally at the crossroads of the main north-south and east-west axes of the city, and metaphorically at the crossroads of Glasgow’s graduation from a quiet backwater to a serious player in world trade,” wrote Gilliland in his book The Grahamston Story

Glasgow’s first theatre was actually built in Grahamston, just outside the city boundary to appease those who didn’t want the “house of the devil” on their patch.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to Gilliland, it was ransacked by a mob on opening night in 1764 but lasted until 1780, when arsonists torched it.

It has been estimated that 10,000 people were displaced in order to bring the railways into St Enoch and Central.

Central Station was completed in 1879 with eight platforms and eight lines brought into the city - all which ran over Grahamston’s middle section.

The western side of the village, including St Columba’s Church, remained intact until the turn of the century, when the remainder of the village was demolished to make way for a station extension.

However two buildings remain - Duncan’s Hotel, now the Rennie Mackintosh Hotel in Union Street, and the Grant Arms in Argyle Street at Central Station bridge.

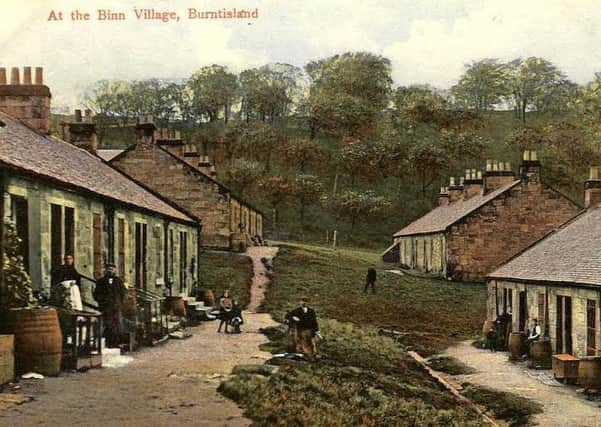

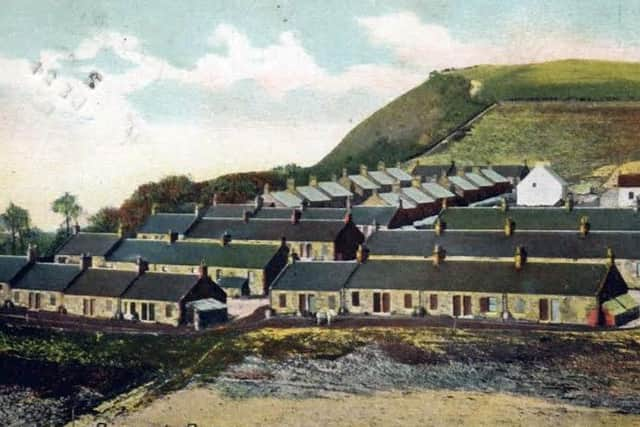

Binnend, Fife

Built for workers at the shale oil works built at Binnend in 1878, it sat around a mile north east of Burntisland with views to the Firth of Forth and Edinburgh.

The village came in two parts - the High Binn and the Low Binn east of the plant.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to local historical research, around 560 people lived at High Binn at the time of the 1891 Census - when Binnend was really at its peak. A further 192 people lived in the smaller settlement. Around a third heads of household were Irish, with the remainder local to Fife or other shale mining areas in the Lothians.

Overcrowding was commonplace, with some beds used on a shift system with some sleeping in the space between the ceiling and the roof, it is said.

The success of the mines was relatively short lived and they were closed down in 1894 - although some people chose to stay in the village despite a lack of running water, electricity and sanitation.

Troops and dockworkers used the empty cottages during WWI with war widows later given a choice of properties. High Binn later became a popular holiday spot for those seeking respite from the city.

The last resident, George Hood, left in 1954. Some remains of the old cottages are visible today but the site is very overgrown and prone to flooding.

Bothwellhaugh

Another legacy of Scotland’s rich industrial past is Bothwellhaugh in the Clyde Valley, a coal mine and village which vanished in the 1960s with the land now forming part of Strathclyde Country Park,

Formerly owned by the Duke of Hamilton, several collieries were developed following the discovery of extensive coal seams on his estates.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe lease of mineral rights at Bothwellhaugh was then granted to the Bent Colliery Company, who sunk two pits on the site, and named it the Hamilton Palace Colliery.

The village accordingly became known as “The Pallis” and had two churches, two schools, a miner’s welfare club and 450 homes.

But it had no pub - on the orders of the Duke.

At its peak, the mine employed around 1,400 workers and produced around 2,000 tonnes of shale a day.

The pit closed in 1959 with residents dispersed. Bothwellhaugh was finally demolished in 1966 and latere flooded to create the loch at Strathclyde Country Park.

St Kilda

People first made it to St Kilda - an archipelagos which sits deep in the North Atlantic around 40 miles north west of Uist, during the Iron Age.

They finally left in 1930, never to return to the famous rock that is now a seabird sanctuary.

It was the gannets, fulmars and puffins that provided islanders with much of their resources - food, feathers and oil. Some they eat and used themselves with the remainder swapped for rent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAbout 180 people lived on St Kilda during its busiest spell in the late 1600s, with land latterly rented from the Macleods of Dunvegan in Skye, whose factor would visit once a year to collect rent and sell imported goods.

Settlements were built in Village Bay with summer homes found in Gleann Bay, which looks to the north

Gradually the St Kildans lost their self- sufficiency, relying on imports of food, fuel and building materials and furnishing for their homes.

In 1852, 36 islanders emigrated to Australia but half of them died. It is said that when news reached the island people ‘shut themselves up in their houses and wept for a week’

Food shortages hit and the first St Kilda mailboat -a form of distress signal - was developed with a floating sheep’s bladdder attached to a wooden container containing a letter for help.

Further emigration followed and the island economy broke down to the point where 36 islanders requested an evacuation to the mainland in 1930.