The necklace for a First Nation chief who helped save a Scottish mountain

The piece, by jeweller Maeve Gillies, was inspired by the struggle against the Harris super quarry plans of the early 1990s to raze Roineabhal mountain to sea level to create the biggest roadstone quarry in the world.

Now on show at An Lanntair arts centre in Stornoway, the necklace references the First Nation chief who came to Scotland to help islanders save the mountain from destruction by big business.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

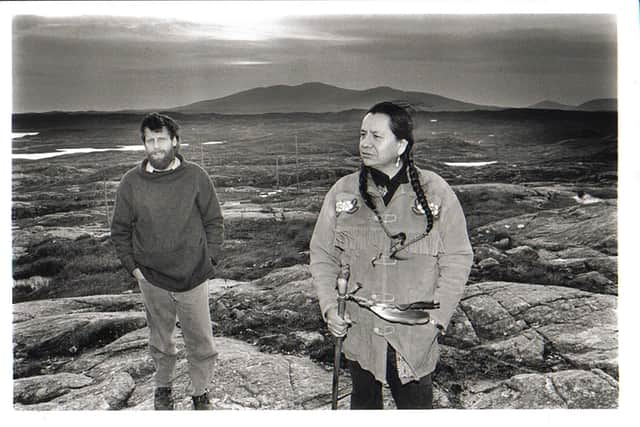

Hide AdSulian ‘Stone Eagle’ Herney, former chief of the Mi'Kmaq of Cape Breton Island, addressed the public inquiry of the sacred nature of the mountain with the super quarry plan finally defeated in 2004 following a hard-fought campaign that lasted more than a decade.

The designer said the necklace had started as a personal piece given her husband’s own Native American lineage, but that local reaction and the piece’s resonance with ongoing issues for islanders, such as land reform, had given it added meaning.

Ms Gillies said: "It was an honour to create this one-of-a-kind necklace with rare native stone, telling a story of such significance to the Scottish islands, whose indigenous culture, language and landscape continues to be under constant threat of change and loss today.

"The necklace has become something much bigger than itself. It has really involved local people and it seems so relevant to them.

“At the start, it was certainly something very personal, but then it became something about community.”

The piece is made from black-and-white Harris anorthosite collected from the foot of the mountain, with Ms Gillies designing the necklace in the ‘squash flower’ style that was forged by the Navajo in the late 19th century and which remains synonymous with First Nation craftsmanship.

The Harris stone comes in a mixture of very dark and very light pieces.

Ms Gillies said: “This dark and light came to represent the issues around the super quarry. So many people thought it would be a good thing as it would bring money and employment, but it was found only around three dozen jobs would be created, with no guarantees they would go to local people.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStone Eagle came to Scotland given the risk the super quarry posed to a habitat for golden eagles – a species he had protected from a similar industrial plan in Canada.

Ms Gillies said: “The elders of the Harris community presented Stone Eagle with a piece of summit rock as a gift. He was horrified as he considered it sacred. He took it home under his protection and it was returned to the mountain when it was set free.”

The stone at the centrepiece of the ‘super quarry squash blossom’ necklace is surrounded by two eagles to represent the birds of Roineabhal.

Alastair McIntosh, writer and human ecologist who invited Stone Eagle to Scotland, said: “My wife and I went to see the piece in An Lanntair recently. It blew me away, bringing a tear to the eye.

"This is a profoundly important piece of art. It speaks not just to what happened with the quarry, or of Chief Stone Eagle. It speaks to the light and dark in every one of us."

A message from the Editor:Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by Coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.