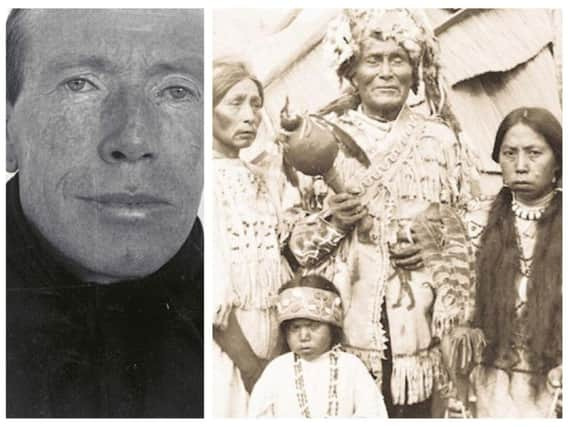

The lost story of a Shetlander who became a champion of First Nation Canadians

Now, the lost story of James Teit, from Lerwick, has finally been told by anthropologist Wendy Wickwire, Emeritus Associate Professor of environmental studies at Victoria University, who first started the massive transatlantic research project into his life more than 40 years ago.

At the Bridge: James Teit, an Anthropology of Belonging, looks at the Shetlander's life from his radical beginnings on this islands to his deep connection with the people of Spences Bridge, who he first encountered at his uncle's shop and then during summers when he worked as a big hunt guide.

A FRIEND TO THE PEOPLE

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTeit fully immersed himself in his adopted homeland and within eight years of arriving in 1884, aged 19, he was married to Antoko, a young Thompson River - or Nlaka'pamux - woman.

Crucially, it is Teit's anthropological and campaigning work that is fully explored by Wickwire. Teit worked on the ground, collecting place names, drawing maps and recording songs and music from his new community.

He went on to represent chiefs in disputes over colonial land grabs. He was unlike other anthropologists of the day, argues Wickwire, because he did not view people through a Christian, colonial prism. He saw the people only as their own.

But the work of Teit, was employed by German-French anthropologist Franz Boas who visited Spence's Land some 10 years after the Shetlander arrived, has been largely forgotten. Not a scholar, Tait is usually referenced as a research assistant or helper to Bonas, despite his input to tens of thousands of pages of research.

But Boas himself was clear of Teit's worth.

In a letter to his family on 21 Sept. 1894 Boas described Teit as “a treasure! He knows a great deal about the tribes. I engaged him right away.”

TIME FOR RECOGNITION

Indigenous communities also knew of Teit's influence on the recognition of their land and people, but the history books have scarcely recorded his impact.

Wickwire, in an interview with New Books in Anthropology, said: "To me that is one of the main correctives of this book that I hope people will see what happens when the first chapter I look at who gets into the pantheon of heroes in the anthropological world.

"His name doesn't exist in histories, you can't find him.

"If you do find him, he is cast incorrectly, he is just not there. It gave me a really important hook for this book."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdShe said that six First Nation communities in British Columbia had hosted events to mark publication of the Teit biography.

Wickwire added: "They were buying two or three copies and speaking so positively about the importance of Teit. He is known there, but he has never been written up in this way."

SHETLAND ROOTS

The author argues that it was Teit's strong sense of identity as a Shetlander that helped form his approach to anthropology.

In a 1901 British Columbia census, Teit described his nationality not as British but as Norse , his language not as English but as Shetlandic and his religion as, not Presbyterian which he was raised in, but as free thinker.

She added: "And you can see where his allegiances lie and I think that is a big part of his persona. For an anthropologist of this period, he is a clean slate.

"He saw Shetlanders as an oppressed Norse, Scandinavian minority so when he hit British Columbia and saw what was being done to indigenous people, he felt he saw the story before.

"That is where the Shetland side of the story took me. That is where it became so exciting. I found a cohort that he was raised with in 1870s who were quite fired up as teenagers. They felt they were being colonised by the Scots.

"Teit's generation was looking back to the 15th Century and retrieve that side of their past, changing their names, reading Scandinavian history."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIndeed, Teit changed the original spelling of his surname - Tait - after learning of Norwegian Jan Teit who settled on the island Fetlar in the 12th Century.

As he explained in a letter to his uncle Robert Tait in 1905, “[Teit] is the real old original and proper way of spelling the name.”

Wickwire added: "They were fired up. Their dialect which by the 1870s was definitely English but it was not mainland Scottish English. It was very much a mixture.

"It was considered inferior but Teit's generation thought it was a high form of speech. They wrote novels, they wrote poetry ...they were really into history and genealogy and really into the idea that the Scots landlords had colonised Shetland and that the outer lying had been really oppressed.

"When he arrived in British Columbia at 19 he gravitated pretty quickly into the local community. He thought 'oh my gosh, its the same'."

POLITICAL ACTIVISM

Teit was for 15 years politically active in representing the Nlaka'pamux people.

Wickwire said: " There was nothing known about that time ...you had to go to archives to collect what he was doing with these chiefs in his community, who spoke no English but who he knew were so articulate, so intelligent, so fired up and had so much to say about land theft.

"The colonial project in British Columbia, according to the chiefs, had taken place on stolen land.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"Teit's 10 years of immersion in the language allowed him to get into their complex history as they understood it, their history of oppression as they understood it....so he was once of the first to be able to listen, to understand and help them put their arguments forward in terms of petitions, letters, trips to Victoria, the capital of British Columbia to deal with the very autocratic, authoritarian premier and multiple trips to Ottawa."

When the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia was formed in June 1916 in Vancouver, Teit was selected to serve on its executive committee, along with several aboriginal leaders.

THE LONG JOURNEY

Wickwire first encountered the Teit story when, in 1977, she heard some musicians play some traditional Nlaka'pamux songs, which she later learned had originally been documented by the Shetlander.

A meeting with one of Teit's sons - he had six children with his second wife - in 1990 crystallised her interest in the story.

Wickwire added: "Teit's son was was really wondering why his father was so unrepresented by the histories he was looking into.

"He said 'we have got to do something on my father'.

"Even in 1990, I didn't know how long it was going to take.

"I really have been living alongside him for decades."

Teit died in October 30, 1922 in Merrit, British Columbia, and is buried there.