The diet of the Picts revealed in breatkhrough study of skeletons

The Picts avoided fish and preferred to eat barley, beef and other meats despite their seafaring ways and close proximity to the coast, the study has found.

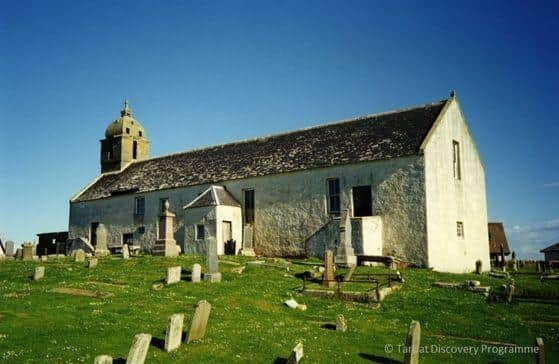

Dr Shirley Curtis-Summers, Lecturer in Archaeological and Forensic Sciences at the University of Bradford, studied 137 skeletons buried under the old Tarbat Parish Church in Portmahomack, Easter Ross.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe remains span hundreds of years of Highland history, including two periods of Pictish life: from the 6th century when the land was used by a farming community, and subsequently, as a Pictish monastery.

The skeletal analysis showed that a small Pictish community which settled between 550 and 700AD ate a healthy diet of plants such as barley, with some animal protein such as beef, lamb and pork, from both farming and small-scale hunting.

It is possible that fish wasn’t eaten given that salmon, for example, held an important and special place in Pictish folklore.

Dr Curtis-Summers said: “Pictish sea power is evident from archaeological remains of naval bases, as at Burghead, and references to their ships in contemporary annals, so we know they were familiar with the sea and would surely have been able to fish.

“We also know from Pictish stone carvings that salmon was a very important symbol for them, possibly derived from earlier superstitious and folklore beliefs that include stories about magical fish, such as the ‘salmon of knowledge’, believed to have contained all the wisdom in the world.

“It’s likely that fish were considered so special by the Picts that consumption was deliberately avoided.”

The Picts were one of Scotland’s earliest civilisations, skilled in farming and with a sophisticated culture, but until now little has been known about what they ate.

Dr Curits-Summers analysed the bones for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios and combined this with analysis of the animal bones found on the site to reconstruct the diets of the communities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt appears that the Pictish males ate more animal meat than females, possibly because they needed more sustenance to hunt.

Dr Curtis-Summers found that the majority of Pictish monks who lived in the simple monastery between 700 and 1100 ate very little fish at all.

However, they ate more meat than their Pictish lay predecessors, possibly due to being more skilled as pastoral farmers.

The monks also had a diet of plant foods such as barley to make bread and pottage – a vegetable soup or stew - and meat consumption included beef, lamb, pork and venison.

A large amount of animal bones was found from this time but barely a handful of fish remains.

However, one middle-aged monk stood out from the rest of his brethren by having higher a carbon isotope ratio that suggests a noticeable intake of fish.

Dr Curtis-Summers said: “It is possible that the monks at Portmahomack followed an early form of fasting that did not stipulate fish as a replacement for meat on fast days, and possibly some residual belief in the avoidance of eating revered fish, such as the salmon of knowledge, led to its absence.

“It’s not that they didn’t know how to fish, just that they chose not to for their main sustenance. But one monk was consuming fish protein, and it’s possible that he had a higher status, such as being the head of the monastery, with privileged rights to fish. It’s clear that fish was available to this monk and maybe some older monks of higher rank, but this was a rare privilege, possibly associated with entertaining very special guests at the monastery.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was also found that some older monks ate more meat than the younger monks, reflecting a hierarchy at the Pictish monastery.

After the decline of the monastery following a Viking raid in c800 AD, the site subsequently became a parish church, and in the mid to late medieval period, the local population ate a great deal more fish.

Fish bones from this period were found in much greater quantities, and this coincided with growing populations, an increase in the fish trade and fish becoming more popular as a Christian fasting food.

The Pictish monastery at Portmahomack became one of the most important archaeological finds for decades when it was discovered in the mid-Nineties and is still revealing its treasures through scientific analysis such as that by Dr Curtis-Summers.

Dr Curtis-Summers said: “The Picts are commonly associated with being war-like savages who fought off the Romans, but there was so much more to these people and echoes of their civilisation is etched in their artwork and sculpture.

“Sadly, there are almost no direct historical records on the Picts, so this skeletal collection is a real golden chalice. Finding out about the health and diet of the Pictish and medieval people at Portmahomack has been a privilege and has opened a door into the lives they led.”