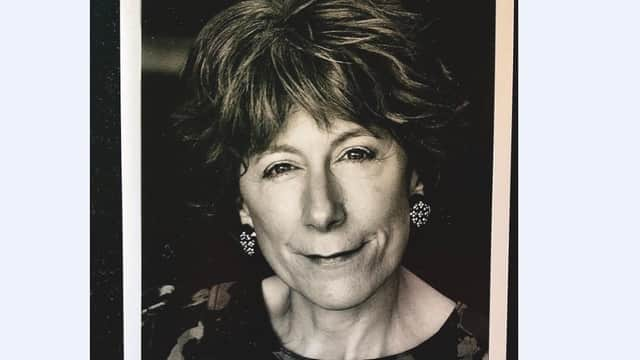

Book review: Rebel Women, by Rosalind Miles

Reclaiming lost narratives has always been a central part of making us more nuanced and subtle about the past, and its indications towards a possible future. It is, however, a game played with sharpened knives, and sometimes they slip.

Miles begins with three figures who should be better known, more widely celebrated and prominent in our stories: Olympe de Gouges, who was guillotined and who famously asserted that if the State treated her as an equal in terms of her execution, why not in terms of her life?; Théroigne de Méricourt, acclaimed for storming the Bastille though she was actually in Versailles; and Pauline Léon, who insisted that women had the right to bear arms. All forgotten, and the female image of the Revolution tends to be the bare-breasted Marianne of Delacroix, who did not exist. But herein lies one of the problems with this book. Should Charlotte Corday, who murdered Jean-Paul Marat in his bath, be acknowledged as a heroine, or as a counter-revolutionary opponent of change? The difficulty with the excavation story is the other untold stories.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe best chapter deals with these problems. How does a feminist deal with figures such as Margaret Thatcher (who famously thought removing VAT on tampons was unnecessary), or Indira Gandhi, or Madame Mao, or (oddly unmentioned) Golda Meir or even the now problematic figure of Aung San Suu Kyi – so eloquent about rights, so silent about the Rohingya? What does a liberal individual make of someone like Valerie Solanas, author of the SCUM manifesto (the Society for Cutting Up Men), or the Empresses Messalina, Theodora or Wu Zetian? Although the book manages to be as non-Eurocentric as possible, there are oddities, such as strange praise given to Hong Xiuquan, the instigator of the Taiping Rebellion, who thought he was the little brother of Jesus, but gets a “pass” because he did not approve of foot-binding. I could list several of the inspirational people who slip past – Virginia Woolf, Aphra Behn (the first woman playwright to make a living from her writing), the composer Hildegard of Bingen, the philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria and more. In the helter-skelter that takes in Germaine Greer and Greta Thunberg, the founder of Cosmopolitan and Rose McGowan, Susan B Anthony and Mary Wollstonecraft, Princess Diana and Doris Day, the hiatuses seem somewhat curious.

What is particularly difficult in this book is the style, not the substance. Of course, a book about the outspoken, those who refuse to be silenced, those who reserve the right to scorn the patriarchy must, in some ways, reflect that mode of discourse. The tone veers between aggrieved and sarcastic, as in “while men took of the heavy man-work of hanging out with other men, thinking and drinking (excuse me, debating the issues of the day), which always took more drinking and more thinking about more drinking and thinking”, or the rather coy reference to the readers as “mes amis”, or puns such as men-struation, or even the rather odd, snide reference to Gladstone as “hobnobbing with prostitutes (rescuing fallen women, surely?)” and Queen Victoria referred to as a “pint-sized potentate”. Or even more denigratory: “the ever-rampant, last-prick-standing phallusy of history!” The bite-size chapters are headed with headline-ish raised eyebrows – “Let’s here it for the f-word”, “Female incapacity : innate or man-unfactured?” “A for effort, B for back in your box”. Nobody would suggest that women are obliged to be decorous and demure and polite, but there is truth in the saying that you catch more flies with honey than vinegar.

The book ends with its manifesto: human rights, not women’s rights, equality before law, protect the female body, free the female mind and free the male (by “training for non-violence”, a proposition at odds with the valorisation of female anger). What struck me most sadly about this book is that it has little to say about culture, save for a few dropped references to Austen, the Brontës and Mary Ann Evans (also known as George Eliot). Nor does it engage with genuinely radical feminist thought. Though it begins in France, it does not end there, and you can search in vain for reference to Hélène Cixous, Luce Irigaray, Julia Kristeva (despite her work in extending rights to the disabled, an extension of Olympe de Gouges’ concern with abolition), Simone Weil, Hannah Arendt, Mary Warnock, Susan Neiman, Iris Murdoch, Gayatri Spivak or Donna Haraway. Instead, you can read about Magic Marta, Helen and Rob from the Archers, Roe vs Wade and Calamity Jane. This book will not convince the entrenched (I can’t see it being Donald Trump’s Books of the Year), but nor will it enlighten those who have tried to think anew.

Rebel Women by Rosalind Miles, Virago, £25