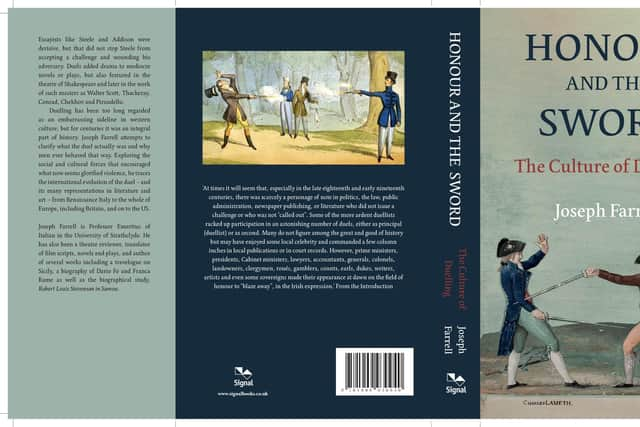

Book review: Honour And The Sword By Joseph Farrell

Joseph Farrell quotes this exchange early in his fascinating examination of the Culture of Duelling, and it is very much to the point. The two characters, Ivor and Guy, recognise that 150 years ago their understanding of Honour would have compelled them to accept a challenge to a duel, even in certain circumstances to offer one. Guy, a Roman Catholic (like Waugh himself) remarks that “moral theologians were never able to stop duelling – it took democracy to do that.”

The quotation is characteristically well-chosen, Waugh being one of the comparatively few 20th-century British novelists to have concerned himself with the question of honour. According to the duelling code, it was dishonourable to accept an insult unchallenged; honour required you to accept when challenged to a duel. Shakespeare has Falstaff dismiss honour as a mere word and say he’ll have none of it, but Falstaff was a man ahead of his time.

Advertisement

Hide AdYet Guy’s remark about theologians is worth dwelling on. The Church condemned duelling, even though the Book of Samuel tells of how the giant Philistine champion Goliath laid down a challenge to the Israelites and mocked their refusal of it, until the boy David stepped forward with his sling and stones. Certainly David thought the honour of Israel at stake. Yet this was a duel without conditions or seconds. It might be seen as a preliminary to battle.

Neither the Greeks nor Romans had a cult of duelling; fights between gladiators in the arena had no honour about them. They were coarse entertainment for the crowd. Nor were the jousts between mounted knights duels, though doubtless there may often have been personal animosities. But they were essentially a form of dangerous sport, like boxing today. The cult of duelling really dates from the Renaissance and the developing idea of the Gentleman.

Casanova, a more interesting man than his reputation as a great seducer suggests, fought several duels. Farrell tells of one in Warsaw. Casanova pondered the morality of duelling and “clearly spelled out its paradoxes, contradictions and dilemmas”. In the Warsaw duel he wounded his opponent, after which each showed concern for the other’s well-being and safety; in fact they became good friends. Such a development wasn’t uncommon. Foes who had proved their honour made good friends.

Duelling was made illegal in many countries, among them Scotland, England and Ireland, but was nevertheless practised. Honour demanded it. Cabinet ministers fought duels, the Duke of Wellington doing so even as Prime Minister. Daniel O’Connell, the great Irish “Liberator”, killed a man in a duel. Alexander Hamilton, as everyone now knows from the musical, was killed by Aaron Burr in a duel, even though he disapproved of the practice. Farrell quotes the Cavalier poet Richard Lovelace’s most famous lines, “I could not love thee, dear, so much,/ Loved I not Honour more.” The two greatest Russian writers of the early 19th century, Pushkin and Lermontov, were both killed in duels. Lermontov fought several before the fatal one. Literary men duelled, eager to prove their manhood. James Boswell’s son, Alexander, briefly a Tory MP, was killed in a duel occasioned by satirical verses he had written. Bullies might provoke duels, were even hired or egged on to do so. Duels feature in great Westerns: Shane, High Noon and The Man Who Shot Liberty Vallance. In the last of these the villain provokes the pacific lawyer played by James Stewart to accept that honour compels him to accept a challenge. Here, however, the code is subverted; nevertheless it is the Legend that is printed and holds sway.

Professor Farrell, erudite, intellectually curious author of several admirable books about Italy and Stevenson in Samoa, ranges widely – there is even a chapter on duels fought by women. Democracy, as Waugh’s Guy Crouchback says, killed the practice; we are all with Falstaff now. But what has become of the idea of Honour? Dryden called it “an empty bubble”. Are we better now for its pricking? This splendid book, rich in examples of courage and folly, provokes thought. Read it once for pleasure. Then ponder its significance in our time of false news and slanderous speech.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.