Art reviews: Will Maclean | James Morrison | National Treasure

Will Maclean: Points of Departure, Edinburgh City Art Centre *****

James Morrison: A Celebration, 1932-2020, The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Advertisement

Hide AdNational Treasure: The Scottish Modern Arts Association, Edinburgh City Art Centre ****

The fairies of old Caledonia, the sidh or sith, did not have sparkly wands and twinkly wings. They were often dark and sinister and always capricious. They seem to have personified the unpredictable forces governing the precariousness of life and the arbitrary cruelty of fate in the difficult lands of the north and on the dark, stormy waters of the northern seas. One thing that struck me seeing Will Maclean: Points of Departure, the beautifully laid out retrospective of his work at Edinburgh City Art Centre, was the sense that these dark spirits and the shadowy realms beyond our immediate consciousness that they inhabited are never far away and that precariousness is also central concern of his work.

In works like the Night of Islands prints – an outstanding achievement in any story of printmaking – and others too with references to the Clearances and to the Highland emigrations to Canada, when whole communities were made homeless and banished, the precariousness of Highland life is starkly manifest. These same concerns seem also to be echoed in works about fishermen and fishing in dangerous waters like the The Drowning for instance, or the magnificent Skye Fisherman in Memoriam. In other works like Northwest Passage – Arctic Route, or Ice Log, he reflects on how the Arctic explorers braved ice and darkness in unknown waters. Here, as well as his manifest admiration for their courage, the ominous difficulties of the unknown geographically seem to stand for the difficulty of the unknown mentally. In a work like Bard McIntyre’s Box, too, we look directly into the shadows where the Caledonian fairies once lurked. The shamans or priests of the forgotten religions of prehistory who sought to mediate with the spirits that seemed to govern fate are here too. Alignment Receiver Calanais is a box of imagined instruments for the builders of the mighty and mysterious stones of Calanais.

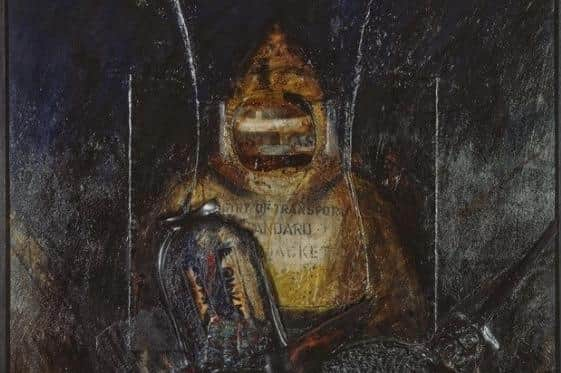

Not that Maclean’s work is all dark and sinister. Abigail’s Apron from 1980, for instance, a touching memorial to a Highland aunt, is simply poetic, but already Symbols of Survival, a key work from 1976 inspired by a US wartime survival kit, suggests voyages into danger, while a figure with black butterflies for eyes and mouth in Window Visitation North Uist, again from 1980, suggests the nearness of the uncanny. That word literally means the unkent, or unknown. Maclean enjoys the unknown and not always for any sinister implications he may draw from it. One of the most intriguing works here is Time Wheel Library from 2008. Characteristically it is built around a found object, in this case a corroded bronze wheel embossed with enigmatic symbols. Quite inscrutable but evocative, it looks like a fairground fortune-telling wheel looking into the past, not the future. Riffing on the idea of museums, objects of unknown use like this, representing a kind of inscrutable memory, are a frequent motif in his work.

Memory merges with the precariousness of life in Atlantic Messengers, a group of three works inspired by St Kilda. Perched on rocks in the middle of the ocean, no community was more precarious. Its people scaled the islands’ immense cliffs to glean a perilous harvest from seabirds nesting there. Cut off from the wider world, they sent messages into the unknown in little boats. Incorporating gannets’ eggs from St Kilda cast in resin that looks like amber, these Atlantic Messengers commemorate that slender link, not only as it was then, but also also as a metaphor for art itself carrying messages like flies in amber.

With the Clearances, greedy landlords became a devastating new factor in the precariousness of Highland life. In Lewis, however, people fought back. One of Will Maclean’s most notable achievements is the group of monumental cairns to commemorate this heroic rebellion, collaborative projects that he led, all documented here.

Advertisement

Hide AdMaclean works mostly with assemblage, but the late James Morrison, currently commemorated at the Scottish Gallery, was always very much a painter. Born and trained in Glasgow, from 1965 he lived in Montrose. There he deployed his skill to paint the Montrose Basin and the wide skies of Strathmore like no one else. He had also lived at Catterline for a period, however, and a work here from 1963 shows him painting the same fishing nets there as Joan Eardley. Like Eardley, too, Morrison understood and experimented with free abstraction, but was not diverted by it. Instead he used its freedom to paint a new and more engaged kind of landscape. His painting is not nearly as precise as it looks. Initially he let his paint do what it will. If you look closely, runs and dribbles are effortlessly incorporated into the image and paintings here simply of the sky are reminiscent of John Schueler’s work, but Schueler’s wide skies are intended to be abstract. Morrison’s painting is always grounded. As we look at his wide horizons, we are conscious of our own tiny scale. This effect is at it most thrilling in works done in the Arctic. Few painters have suggested the drama of icebergs towering above the ice fields so dramatically. Unusually, too, in one of the most striking Arctic pictures, Iceberg Collage, he has used collage and it suggests vividly the jagged ice of the berg. Perhaps he was conscious that his skill as a painter sometimes seems too easy and repetitive. He knew he needed something extra to carry the conviction he was seeking. It is there in all his best work however and it will surely endure.

Alongside Will Maclean at ECAC, there is a show selected from the Scottish Modern Arts Association collection, National Treasure, which quietly but eloquently tells a scandalous story. The SMA was set up in 1907 by a group of public spirited individuals to acquire and preserve for the nation the best of contemporary art, principally but not exclusively Scottish. The works in the show demonstrate how the association did this with skill and discernment. There are outstanding works by FCB Cadell, William McTaggart, Alexander Roche, Ian Fleming, Robert Burns, James Cadenhead and DY Cameron. Notably they also bought work by women artists from an early date and among others the collection includes Bessie McNicol, Katherine Cameron, Mary Cameron, Anne Redpath, Winifred McKenzie and Perpetua Pope.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe long-term objective was to establish a contemporary gallery. When this finally happened and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art was established in 1960, naturally the collection was offered to the nation, but outrageously this magnificent gift was rejected. Admittedly the new gallery was small, but one suspects that really, like a later administration which tried to dump the Scottish collection altogether, the ambition was not to have a Scottish national gallery at all, but an international gallery of nowhere in particular. Just one picture was taken from the SMA’s proffered gift, by William Orpen, an Irish painter. Happily the collection then passed to the newly created Edinburgh City Art Centre. There a distinguished succession of dedicated curators have built on this munificent gift to create what is now one of the most representative collections anywhere of the Scottish art of the last hundred years. As the riches on view here, both familiar and unfamiliar, demonstrate, all they need now is more space and no doubt more staff and more cash to be able to show more of it more regularly. Nevertheless, as the two current shows discussed here demonstrate, even with limited resources they are doing a great job.

Will Maclean until 2 October; James Morrison until 25 June; National Treasure until 16 October