Art reviews: The Love of Print | Ron O’Donnell | Glean

The Love of Print, Kelvingrove Art Gallery & Museum, Glasgow ****

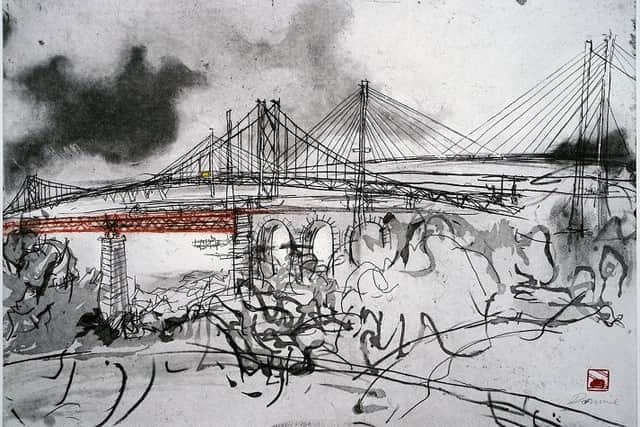

Ron O’Donnell: Edinburgh – A Lost World, City Art Centre, Edinburgh****

Advertisement

Hide AdGlean: Early 20th Century women filmmakers and photographers in Scotland, City Art Centre, Edinburgh*****

The Scottish printmaking workshops have proved to be one of the most successful initiatives in the visual arts in recent times. Begun by artists and only later, if at all, receiving any public money, the early history of the workshops always seems to be illustrated with similar black and white photos of artists pushing wheelbarrows or struggling to manhandle heavy presses into unpromising-looking Victorian premises. Such images illustrate vividly how these workshops were and have remained essentially a kind of cooperative. They really had to be. Few artists could afford the kind of equipment most forms of printmaking require. Correspondingly, the creation of workshops brought about an ongoing renaissance of artists' printmaking in Scotland.

The story began in 1967 with the foundation of Edinburgh Printmakers. Their breakthrough came when they won a grant from a sceptical Scottish Arts Council. This success encouraged others and in 1972 what is now Glasgow Print Studio was founded and its 50th anniversary is marked by The Love of Print, a major exhibition at Kelvingrove. The Glasgow project began with eight founder members. Two of them, Beth Fisher and Sheena McGregor, ran the place initially in small premises in St Vincent Crescent.

All of the original eight were either teachers or students at Glasgow School of Art. Among them, Philip Reeves was a key figure. He had established printmaking at the School of Art and had also been closely involved in setting up the Edinburgh workshop. The Glasgow workshop moved first from St Vincent Crescent to an industrial building in Ingram Street and then in 1987 to its present premises in King Street. Early members included John Byrne and Alasdair Gray and both are well represented here. In 1977 the studio started mounting exhibitions as it still does, but it was also a multi-disciplinary place. There is a poster here for Byrne’s first play, Writer’s Cramp, premiered in the studio, while Alasdair Gray with Jim Kelman, Liz Lochead and others formed there the self-publishing writers’ cooperative the Studio Press.

Organisation in the early years was a bit haphazard, however, and in 1983, after near meltdown, John McKechnie took over as director. He is still in charge, and in the almost 40 years he has led the Print Studio it has become a formidable organisation. The collegiate nature of the workshop and the pool of expertise that developed there suggested McKechnie’s initiative to invite artists with some reputation but perhaps little or no experience of printmaking to work in the studio along with an expert collaborator. This arrangement, which has brought in all sorts of stars, still continues. Current studio manager Clare Forsyth describes how part of her job is match-making, working out who would work best with whom.

Along with artists like John Bellany and Eduardo Paolozzi, in 1985 Elizabeth Blackadder was among the first artists invited in this way. She had scarcely made any prints before, but the relationship developed into a truly remarkable partnership and over almost 30 years, she produced more than 140 prints, latterly working mostly with Stuart Duffin. A selection here includes several etchings of orchids from a suite she produced in 1993 on McKechnie’s initiative. Other work on display here records how Barbara Rae, Victoria Crowe and many others of their standing have, over the years, also made prints in a wide variety of media.

Advertisement

Hide AdIn the 1980s, the Print Studio was there for the new Glasgow painters. There are three striking prints, two of them enormous woodcuts, by Steven Campbell, for instance. Ken Currie has a set of etchings as brilliant in technique as they are dark in imagery, while Adrian Wiszniewski appears working in several different techniques, most recently in a set of beautiful, laser-cut woodcuts. The next generation have also been drawn into printmaking by the Print Studio’s allure. There is striking work here by Kenny Hunter, Jim Lambie, Christine Borland, Toby Paterson and many others.

The sheer number of prints on display and the overall impact of the variety of techniques and of imagery by so many different artists, familiar and unfamiliar, is very impressive. Inevitably, though, it is also very crowded in Kelvingrove’s cellar-like exhibition space. The arrangement is roughly chronological and some of the stars like Byrne, Gray or Blackadder, are given some space to themselves, but others, like Wiszniewski for instance, are scattered throughout. Philip Reeves was such a key figure it would have been good to see him given some space, but I only found a couple of prints by him. There are some supporting films and other material and also a handsome catalogue. Altogether it is a great story, but the show seems to be more about impact than narrative, so you do rather have to tease it out for yourself.

Advertisement

Hide AdBack east, Edinburgh City Art Centre continues to amaze by the variety and originality of the shows its small number of staff manage to put on. Edinburgh: A Lost World is a selection of Ron O’Donell’s photographs of shops and other interiors in the city which he has photographed constantly since the late 1970s. Much of it is nostalgic, recording a much less homogenous world than we now know. Here is Robert Cresser’s brush shop in Victoria Street, for instance, the workshop of George McKay making bowling green bowls and Crawford’s Tearooms, all photographed in 1978, while Macdonald’s tobacconists on George IV Bridge was photographed in 1980.

There is the unexpected too. An air raid shelter with a war time set of regulations still on the wall in 1978, or the massive boiler with a mechanical face that once warmed the mash in the Caledonian Brewery. It is an astonishing record of how things once were, although there are also eccentric survivors like Sinclair bagpipe makers, photographed in 2010.

Another photography show at ECAC, Glean, brings together the work of eight pioneering women photographers and filmmakers, either Scottish or working in Scotland in the first part of the last century. Here too, the images are remarkable for the what they record. Isobel Wylie Hutchison filmed icebergs in Greenland in 1928, for instance. However, it is the pictures of the Highlands and Islands that are especially striking here.

Dr Beatrice Garvie was community doctor on North Ronaldsay in the 1930s and 40s and photographed the people of the island. The American folk-song collector, Margaret Fay Shaw, photographed her companions while living for six years with the sisters Pèigi and Màiri Macrae on South Uist. Jenny Gilbertson filmed A Crofter’s Life on Shetland in 1931. Isabell Burton MacKenzie set out to document the way of life in the Western Isles before the First World War and did so in a wonderful set of images, while Johanna Kissling’s photos of the people of St Kilda in 1905 – a crowded boat offshore, a grandmother nursing a child, or a group of women and girls offering for sale gloves they have knitted – are unique in the sense of contact with the people of the islands that they give us.

Perhaps the fact that they were women allowed these photographers greater intimacy. Whether or not that is the case, a women’s point of view certainly informed Christina Broom’s photos of the Women’s Marches in London in 1909 and 1911. Her picture of the nurses and midwives advancing towards us, indomitable, and undeterred by the phalanx of policemen behind them, should be an icon of the women’s movement.

The Love of Print until 12 March; Ron O’Donnell until 5 March; Glean until 12 March