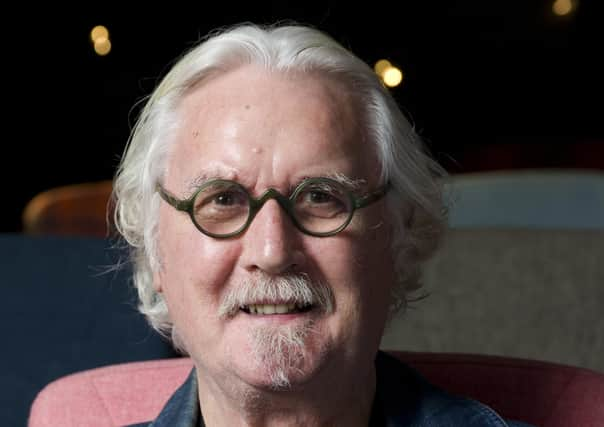

Review: Billy Connolly on the ‘darkness and joy’ of his childhood

Why wasn’t he bringing up his daughter Daisy in Scotland? Was he proud of his Glasgow roots? Did he regret the offence caused by making fun of religion in skits like The Crucifixion and The Last Supper?

The interrogation came in a BBC Scotland programme called Open to Question, dug up for this retrospective of the Big Yin’s life and work. It wouldn’t surprise me if TV producers watching last night nick the idea of 100 teenagers in school uniform disarming celebs, then alarming them. Out of the mouths of babes and all that.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHalfway through Open to Question the pimply chairman told Connolly to expect some tough questions. Reeling from the opening onslaught, the Big Yin pretended to faint.

Why, he was asked, did he portray his ain folk as “ignorant, bigoted morons?” The retrospective cut to Connolly now for his answer: “I’m a comedian, I’m one guy with a microphone. How can I offend a whole nation?”

He can’t, not really, otherwise you’re all a bunch of big jessies. But he’s more than just a comedian. He was the funniest man in Britain back in the 1980s when Open to Question was recorded and he still is today.

Like Clive James when the great Australian wit received his intimations of mortality, Connolly, who has Parkinson’s disease, has become prolific through books, films and series like this. Billy and Us comes in six parts, the opener focusing on his upbringing when he was the same age as the kids in Open to Question and even younger.

Connolly will be aware that the comedian who claims to have resorted to humour in the playground to protect him from the bullies has become a cliche, the sheer number who do this provoking scepticism.

Nevertheless he is a product of his times, the immediate post-war years, when the beatings came from the teachers and often happened at home. He insisted he exaggerated some of the grimness when devising his famous routines. Nevertheless, his mother left him when he was very young and his father sexually abused him. Even here, he thought there might be some comic potential. “I threw out a couple of feelers but there’s no colder subject on earth,” he said.

They may have been embroidered but his rambling stories of hardship resonated with the “children” of Connolly, the younger generation of Scottish comics he inspired. In Janey Godley’s house, too, coats were flung on beds in winter for extra warmth, while for Gary Faulds, if a family row broke out, Connolly’s LPs would calm everything down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdConnolly summed up his childhood as being about “darkness and joy”. The latter would be the freedom to embark on a camping expedition by bicycle, his father unaware the exotic location was Clydebank. But school dominated the programme – “the experience stays with me to this day”, he said.

In primary he was sat in a section of the classroom he called “Stupid but Saveable” – nowhere near the brainy kids but separated from the no-hopers forever clattering their desks. At secondary, Connolly “mentally cracked” but while he didn’t think he suffered by “flipping out”, he wouldn’t recommend it to other young minds. “[My] inability to be educated made me think differently from everybody else and I’m grateful for it,” he added.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.