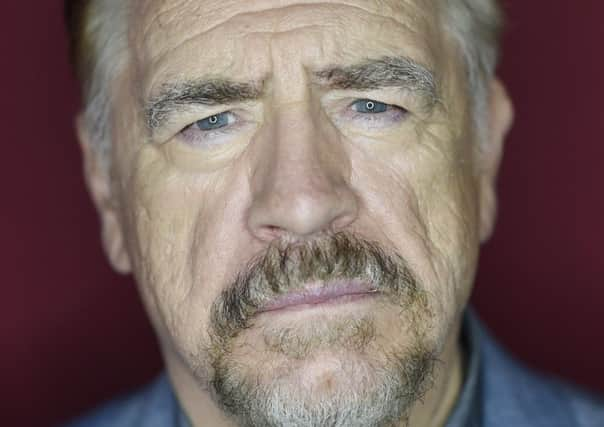

Interview: Brian Cox on playing Sir Winston Churchill

I’m standing in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh, in front of Sir James Guthrie’s portrait of Sir Winston Churchill and Brian Cox is telling me a story. It’s about his Uncle Geordie and the war leader, who from 1908 to 1922 had been the less than popular MP for Cox’s home town of Dundee.

“Churchill, who was invariably ill, is being carried into the city square on a chair on two poles, by four men. My uncle shouted to these guys ‘how much did he pay ye?’ and one of them shouted back, ‘a quid’. My uncle said, ‘I’ll gie ye twa if ye drap ‘um.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So that was the impression that I had of Churchill and my Uncle Geordie used to say he was a chancer, a terrible man. He was unpopular in Dundee because he changed parties, from Liberal to Tory, and for his handling of Ireland, which didn’t go down well, especially with the Irish community, which included my family. He put Edward Carson and Michael Collins in a room together to get the deal whereby Northern Ireland was created and most of the indigent population of the city felt that was a bad compromise. They were agin that.”

We’re talking about the wartime leader because Cox has taken on the role in Jonathan Teplitzky’s film, Churchill, which covers the three days running up to the D-Day Landings in 1944. It’s a different take on the man we are accustomed to seeing, and Cox gets under his skin to portray a different side to the national hero, revealing a more fragile, fallible, flawed character. Scarred by guilt over his responsibility as First Lord of the Admiralty for the slaughter of thousands in the beach landings at Gallipoli in the First World War, Churchill is desperate to stop a repeat in Operation Overlord.

“After he had lost thousands of troops at Gallipoli in the First World War, he resigned and went immediately to the front in France with the Royal Scots Fusiliers. That was a penitent act and he didn’t want the same thing to happen again,” says Cox.

Cut out by Eisenhower and Montgomery, he’s shown as a man also plagued by ill-health and the black dog of depression, but one who rises to the occasion with a show of oratory that gives hope to the masses.

Playing the part of Churchill, all of it filmed in Scotland, has seen Cox reassess his appraisal of both the man and the politician and discover a new-found respect.

“What got me about him was he was complicated. He was an astonishing human being: a soldier, poet, painter, strategist, politician,” he says. “He wasn’t universally liked, but he was a maverick and stood up for what he believed in so he had this ability to reach his moment finally, at the age of 65, becoming prime minister and doing this extraordinary job. But that all came at some cost, and he was amazingly human.

“At the time of the D-Day Landings, he had had pneumonia, probably a heart attack, and he’s coming up for 70. He was frail, drank a ridiculous amount of champagne and whisky, and slept for only three or four hours a night. How he lived to 90 I have no idea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But he had clarity of purpose in relation to the rise of fascism, in a time of appeasement, and he saw that war was the only way to stop it. This was his third war and he’d seen concentration camps – the British invented them in the Boer War – so he knew what Goering was up to, and that they were getting away with murder.”

Where Cox says Churchill came into his own was through his mastery of language and ability to turn words into inspiration through his speeches. “He was a master of the English language and his writing was almost Shakespearean. It was his oratory that got him through, that made him at that moment a man of destiny. He became the conscience of the UK and a bolsterer with these incredible speeches. He really stepped into his destinal position, like Mandela or Napoleon, through believing in his principles.”

The film also makes great play of how the Churchill we are used to seeing was in fact a construct, aided by the props of cigar, Homburg hat and V-sign, created by Churchill and his loyal wife Clemmie, played by Miranda Richardson – “phenomenal,” according to Cox, “one of the best actresses I’ve ever worked with, so inventive and present.”

Just as Churchill donned the round glasses and puffed on a cigar, so Cox adopted the persona by piling on two stones and shaving his head. “They filled in my dimple too,” he says, sticking a finger in his trademark cleft chin. “Putting on weight wasn’t a problem. I like food, and I didn’t want to do fat suits and prosthetics.” Once he’d perfected Churchill’s shambling gait, the transformation was complete.

But it was sitting watching TV with his young sons at their home in Brooklyn that Cox really found his way into how to play Churchill. “My boys said you have to watch Family Guy with us, you’ll love it, so I did. And there he was, Churchill, in the character of Stewie Griffin, the baby. Incredibly bright, articulate, with parents who don’t understand him, he communicates with his best pal, Brian the dog. I realised this is Churchill in embryo. And of course every baby looks like Churchill and Churchill looks like every baby.”

Cox made a deliberate decision not to do the strident Churchill voice we are used to from wartime speeches, apart from a rallying broadcast made shortly after the invasion, because it wasn’t in fact his day to day voice.

“He had a rather soft voice in private when he wasn’t giving a speech, so I didn’t do it apart from then. The voice was all part of the show for the British people and it was through the speeches that he gained his sense of purpose. Even my parents finally admitted Churchill did a great job.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“At the moment we need leaders like this, desperately, and they’re just not there. Look at this whole Brexit thing and you see chancers, the horrific Little Englander mentality of that idiot Farage, the appalling opportunism of that clown Bozo Johnston and the namby-pamby ambition of Michael Gove; these are not good guys. Theresa May? She’s just a dullard. And Trump? There’s nothing to be said about Trump, the guy’s an idiot.”

Aged 71, with his blue eyes, cheekbones and dimpled chin, Cox has presence and he’s a great raconteur when we chat over afternoon tea. When he talks about being inspired by the idea of props as enablers for Churchill, with a story about the cancer-ridden Yul Brynner being transformed from frail old man to proud dancing monarch by the opening bars of Shall we Dance, he hums loudly and taps out the beat on the white tablecloth, “da-da-dum-da-da-dum, da-da-dum-da-da-dum”, so hard that the tea cups rattle in their saucers and almost drown out the harpist playing on the Juliet balcony above.

“I thought that’s such a wonderful image for Churchill, because he’s having to deal with his health too.”

Cox too has health issues; he’s diabetic, something he blames on his Dundee upbringing, and today he takes the precaution of delicately rubbing the sugar off the top of his scone. “That’s the bit I don’t want,” he says. “Sure you don’t want one?”

Cox began at Dundee Repertory Theatre at 14, leaving to train at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art a couple of years later. Success came early and he has starred in numerous films, TV shows and plays, and played heroes, villains and everymen, from the heinous Ward Abbott in the Bourne films and the original Hannibal Lecter (Manhunter) to Agamemnon in Troy to burger van tycoon in Bob Servant. Now that he’s older, are the roles just getting better? “Yes, because the human condition gets more acute as you get older, and more puzzling, and ultimately more disappointing. But you learn to laugh at it.”

His family has followed his long career all the way. Today Betty, his eldest sister is arriving with the clan for a special showing of Churchill. Betty and the other sisters raised Cox after his shopkeeper father Charles died of cancer when he was eight and his mother Mary, a jute spinner, suffered several nervous breakdowns. His sister’s imminent appearance seems to have induced in the normally confident Emmy-award winning CBE-honoured actor, a mixture of anticipation and trepidation.

Churchill wasn’t the first portrait we looked at back in the gallery. En route there was Queen Victoria (“The First World War, a family squabble among her grandchildren that caused untold destruction,” says Cox), James Hogg, (“The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, one of Scotland’s best books”), barefoot women in a Dundee mill, (an “uh-huh” of recognition). And right next to Churchill, a portrait of Andrew Carnegie. “Look at that! He’s someone I want to do something on, because nobody does and he is the father of modern capitalism. He’s partly responsible for the awful state we’re in. He was an incredibly conflicted individual.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I’m really interested in characters who stay very much in touch with their inner child,” he says. “The child is the father of the man and Churchill and Carnegie had difficult childhoods. They had to form themselves. Carnegie had the choice to follow his dreamer weaver father or his practical mother, who sold sweeties from her window. He went the practical way and the dreamer got lost. He didn’t die a particularly happy man. That to me is a character worth doing.”

What kind of father does he think he is, with two grown up children by his first wife Caroline Burt, and two with second wife Nicole Ansari, with whom he lives in New York?

“Hopeless,” he says. “It’s the hardest thing to me, fatherhood. I don’t think I’m a particularly good father, I’m not disciplined enough and I’m too soft, too anarchic. And I’ve got a terrible temper. I’ll get very angry, particularly with my youngest as he’s a bit of a chancer.

“They don’t know how lucky they are and I kind of get angry at them taking things for granted in a way. But you can’t damn them because they didn’t have your disadvantages. And my disadvantages turned out to be my advantages. I consider myself lucky to have had them, and they don’t have that, the struggle.”

In fact it’s so that they don’t have that struggle, that Cox is working more than ever. Last year was the busiest of his career. As well as Churchill, Cox filmed The Etruscan Smile and the sequel to Super Trooper. Next up for broadcasting is Succession, HBO’s drama series about a media tycoon and his dysfunctional family.

“In Succession I play a fictitious Canadian media baron, Logan Roy, who gives his empire to his children, then wants it back. It’s written by Jesse Armstrong, who did Peep Show and will be going out in October.”

Despite all the film success, Cox remains a lover of live theatre. He was delighted to return to the Lyceum last year to play Vladimir in Waiting for Godot opposite his old friend Bill Paterson, and they did Beckett’s bleakly hilarious play proud.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“They’re a couple of big kids and it was a joy to do that, and in our own voices. Bill is so west of Scotland and I’m the east, so it’s the different humours. West coast is more ‘poor me’ Rab C Nesbitt, whereas east coast humour is much more surreal, sunny, with crazy ideas.”

Which brings us neatly to the Broughty Ferry burger van man Bob Servant, of which Cox says there will sadly be no more. “It’s a shame. The east coast hasn’t had much of a look-in drama and comedy-wise, but it’s the BBC... what can you say?”

Is the irrepressibly optimistic Bob the closest in character to Cox himself, would he say?

“The interesting thing is my brother had a shop in Monifieth and people said to the writer Neil Forsyth, you’ve based this on Charlie Cox, though he had never met him. Such a character, my brother. People would go in his shop and buy something and he’d say ‘I haven’t any change, only got a few coppers, but I’ll gie you some veg, a couple of cabbages and some mushrooms, do you like mushrooms?”

Cox laughs at the memory. He’s in a good mood because the reviews of Churchill have been praising his performance.

“You can’t get round it, the man was a phenomenon, and that’s what our film tries to examine, the man, warts and all. And it’s a brilliant script.”

So what does Cox think Uncle Geordie would say about his nephew’s portrayal of the wartime PM?

He laughs.

“Och, yer gien the man way too much credit.” n

Brian Cox stars in Churchill, in cinemas from this weekend.