Why couldn't the Romans hold and conquer Scotland?

There is no doubt that the Imperial Roman Army flexed their might on Scottish soil after Agricola first sent a survey fleet in 79AD.

His leadership peaked around 83 AD at the Battle of Mons Graupius- now known as the Grampian Mountains - when 10,000 Caledonians are thought to have died at the hands of a well-organised Roman legion of around half the size of the tribal force raised from 30,000 men.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAgricola returned triumphant to Rome and was highly decorated for his efforts but the victory did not seal Roman influence in Caledonia. Indeed, it coincided with the withdrawal of large numbers of troops.

Shortly after the victory at Mons Graupius, the Romans suffered crushing defeats on The Danube in 85 and 86 in the Dacian Kingdom, now modern-day Transylvania.

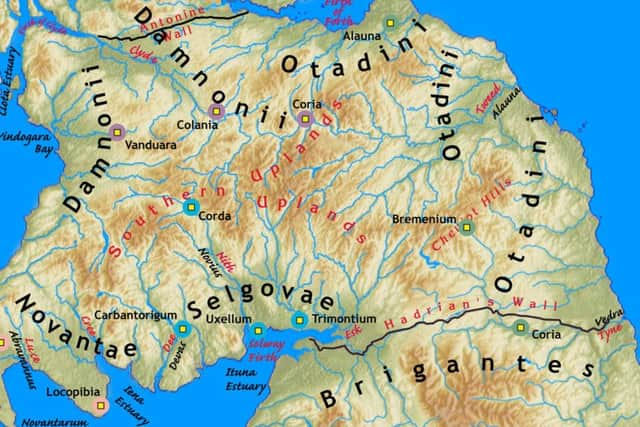

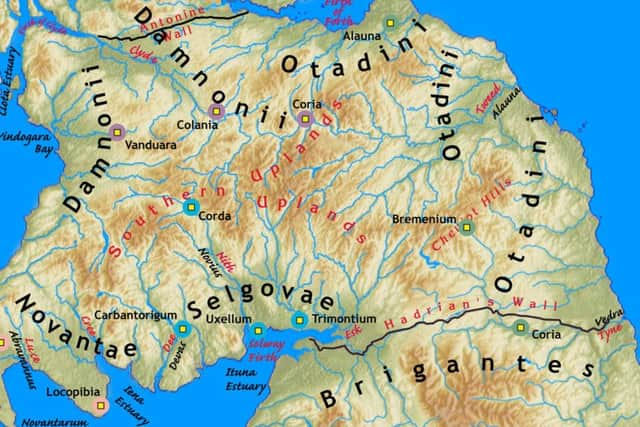

The Romans withdrew to a line just north of the Cheviots - the rolling hills that straddle the modern border between Scotland and England - to a position reached some 12 years earlier and men filtered east.

Several key forts - from Stracathro in Angus in the north to Broomholm and Drumlanrig in the south - remained occupied but further forces filtered away from Caledonia with the start of the Dacian War in 103.

The decision to pull resources from Scotland may well have been made on a “last in, first out” basis but other reasons have been long debated.

According to David Breeze in his book Roman Scotland, Frontier Country, the Caledonians appeared to be “doughty fighters” with Roman statesman Dio crediting the “fearsome and dangerous” men with standing their ground over the two-year battle.

Others have suggested that the “guerilla tactics” of the Caledonians were the perfect assault on disciplined Roman fighters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe mountainous terrain of northern Caledonia has also been considered as a barrier to conquest but, as Breeze points out, the ranges are no greater than those found in other parts of the Empire, such as Spain or the Alps.

Scotland perhaps became simply not worth the bother for the Romans, who were forced to fight and defend deep elsewhere.

“It is difficult to believe that the conquest of Scotland would have brought any economic gain to Rome. It was not rich in mineral or agricultural produce, “ Breeze said.

It is not clear how much this would have dampen the resolve to rule, given “Rome considered she had the right to rule the world,” Breeze added.

Caledonia’s tribal lands and society may have been just too unruly for the Romans who may have struggled to impose their own government and currency. Manufacturing, such as pottery and metal work, were not well developed.

Caledonians were, however, able enough to rise to the huge test of the advancing Roman army and raise battle groups of their own. The tribes at this point probably had their own Kings with society organised well enough to feed itself.

However, the situation was not help by Britain being “on the very edge of the known world,” Breeze said.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe added: “Perhaps if the tribes had not been so warlike, the mountains so high, the lack of economic benefit so obvious, geographical and social difficulties so great, Rome might have triumphed.”

The Antonine Wall - stretched from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde and the most northerly frontier barrier of the Roman Army - was abandoned around 165 AD with the troops returning to Hadrian’s Wall, around 100 miles south.

The Roman Army buried part of the wall with alters and weapons thrown down wells and stashed in pits. T

Timber buildings were burnt as the Caledonia was departed.

Meanwhile, the new tribe of the Picts started to form.

DOWNLOAD THE SCOTSMAN APP ON ITUNES OR GOOGLE PLAY