Whisky firm reviving malts from Scotland's lost distilleries

Scott Watson, co-founder of The Lost Distillery Company, said more than 100 distilleries in Scotland – nearly half of all distilleries which have been built in Scotland – closed permanently last century.

He believes that the Scottish trait of being unable to talk about tragedy and grief, along with the high casualty rate in World War I and the politics of the time all contributed to the decline of some of Scotland’s distilleries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

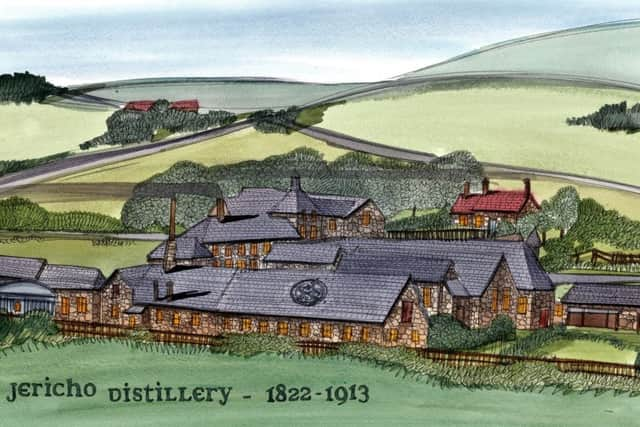

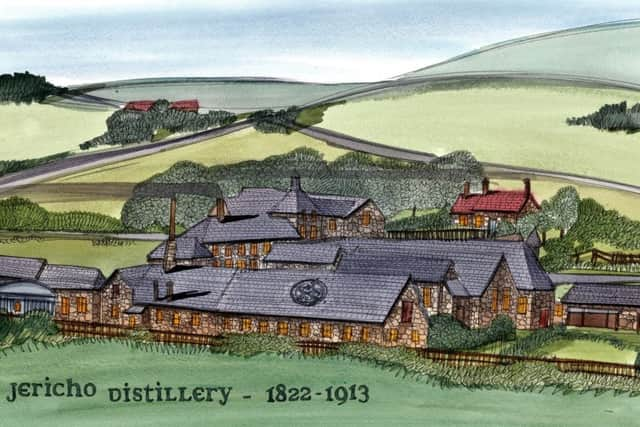

Hide AdWatson’s company has revived a number of whiskies from lost distilleries such as Auchnagie in Perthshire, Jerico in Aberdeenshire, Stratheden in Auchtermuchty, Towiemore in Dufftown, Gerston in Caithness, and Lossit on Islay, which disappeared after small distilleries were either lost or mothballed.

He said: “If you look at somewhere like Auchtermuchty in Fife where the Stratheden distillery would have been the beating heart of the town, and then see what happened to it, you begin to understand the factors which were at play.

“The distillery was set up in 1828 by Alexander Bonthrone and would have provided jobs for so many of the men there.

“All the men would have gone off to war and I think it’s a particularly Scottish thing that when they didn’t come back it wasn’t talked about, it was just too painful.

“Scotland is a very stoic nation, and having a whole generation lost and not coming back must have been absolutely devastating.

“Speaking to people in Auchtermuchty now I find many are totally unaware there was once a distillery there.”

Watson said that as well as many distilleries shutting or being mothballed, and surviving for a few years after the war, there was not the ‘means, the skills or the heart’ to attempt to reopen them for the long-term.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“As well as the high death toll in the war, distilleries were shut down to fight the war effort.

“Everything from the land was used to feed the troops rather than making whisky. Thus the distillation process passed down from generation to generation was lost,” he added.

The industry also had to contend with political factors such as grain imports being banned in 1916, yeast in 1917 and finally in January 1918 all exports of Scotch whisky was banned.

The whisky industry was also hit by the Prohibition Act in the United States in force from 1920 until 1933.

Watson’s company has an archival team led by Professor Michael Moss of the University of Glasgow.

Watson added: “We go out and identify as much as we can about the original distillery and what it produced. We want to know about ten key components, including the size of the still, what its capacity was, whether the distillery was using hard or soft water and what type of wood was used for the whisky barrel and had it been previously used for another spirit. We look at the terroir – the natural setting – and how it affected the barley, whether the water ran over granite or through peat, through rich fertile ground or heather.”

The team then creates a modern-day equivalent of the whisky which is then discussed with a tasting panel of experts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJoe Trotter, the company’s former archivist, said: “While the First World War did not destroy Scotch, it marked the beginning of the end for many. The war brought a changing of the guard, with the big distillers and blenders consolidating the Scotch market.”